Assessing Attitudes, Feelings and Opinions of Women Living With Disability on Their Reproductive Health in Kakamega County, Kenya

© 2021 Consolata Namisi Lusweti, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Disability is defined as “an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions [1]. One billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, have some form of disability, and the prevalence is higher in developing countries. This adds up to between 110 million and 190 million people. Eighty percent of persons living with disabilities live in developing countries, according to the UN Development Program [1].

Introduction

Background Information of the Study

There is no universal agreement on a definition of people living with disability. However, the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) defines disability as ?an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions?; adding that ?disability is a contextual variable, dynamic over time and in relation to circumstances; its prevalence corresponds to social and economic status?. Disability is thus seen as ?a complex phenomenon, reflecting an interaction between features of a person?s body and features of the society in which he or she lives? [2].

There is a strong link between poverty and disability. Poor people have a higher risk of acquiring a disability; they are more exposed to disabling diseases and conditions. At the same time, disability increases the possibility of falling into poverty by being excluded from participation of development initiatives. This cycle of disability and poverty must and can be [1].

The World Bank estimates that 20 per cent of the world?s poorest people have some kind of disability, and tend to be regarded in their own communities as the most disadvantaged. Women with disabilities are recognized to be multiply disadvantaged, experiencing exclusion on account of their gender and their disability. To ensure a safe pregnancy and a healthy baby it is argued that healthcare professionals should focus more on women?s abilities than their disabilities and that care and communication should be about empowering women. Evidence from qualitative research suggests that maternity care needs have not been met for many pregnant disabled women. Many women with disabilities say they feel invisible in the healthcare system, stressing that their problems are not simply medical, but also social and political, and that access means more than mere physical accessibility. Because many women with disabilities face a great deal of unpredictability in their daily lives, they want care that is well planned and which helps to eliminate the unexpected [2].

Women living with disability face many issues that can inhibit or

prevent them from effective parenting. Some of these include the

overwhelming scarcity of information and resources on mothers

living with disabilities. With the availability of the internet, a

number of women living with disability have created websites and

list serves that allow disabled parents to exchange information

and resources. While mothers living with disability encounter

numerous barriers to parenthood, they also find effective solutions

that are comfortable with them [3].

The recommendation of the current UK NICE Antenatal Care

Guidelines is that all pregnant women should access health care

services early. In general, people living with disability may face

considerable challenges in accessing health care services. Little

research exists on addressing maternity issues among Pregnant

women living with disability generally focuses on their disability

rather than their reproductive capability [2].

To ensure a safe pregnancy and a healthy baby it is argued that

healthcare professionals should focus more on women?s abilities

than their disabilities and that care and communication should

be about empowering women [4]. Evidence from qualitative

research suggests that maternity care needs have not been met for

many pregnant women living with disabilities Many WLWD say

they feel invisible in the healthcare system, stressing that their

problems are not simply medical, but also social and political,

and that access means more than mere physical accessibility [4].

WLWD face a great deal of unpredictability in their daily lives,

they want care that is well planned, and which helps to eliminate

the unexpected [5].

Demographic factors of the women living with disabilities and

the able-bodied women have to be considered when looking at

maternal and neonatal health indicators. These included age,

level of education, religious affiliation, number of pregnancies,

and occupation status.

People with disabilities (PWDs) in Kenya live in a vicious cycle

of poverty due to stigmatization, limited education opportunities,

inadequate access to economic opportunities, and access to the

labor market. Women with disabilities are more vulnerable to

human rights violations through neglect and exclusion from

political, socio-cultural, civil, and economic activities. They

face discrimination in access to and utilization of public health

facilities and services and are under-served in terms of healthcare

information [6].

A woman living with a disability tends to be judged and found

ineffective in appearance. This is largely due to negative attitudes

and stereotypes about what they can or cannot do. There are

misconceptions that a woman living with a disability may not be

competent in most areas such as learning or being able to be in gainful employment [3].

Over the past 2 decades, childbirth In Kenya has become more

medicalized and women living with disabilities may therefore

be at risk of being viewed through a medical lens solely because

of their particular.

There are limited special services to assist WLWD and they are

often forced to rely on their families or engage someone whom

they must pay for by themselves, to care for their children and the

position of WLWD in the rural communities is even worse [7].

There are limited strategies or activities by state bodies or health

care institutions that take into account the specific health needs of

young girls and women living with disabilities [6]. Unfortunately,

because of this, women do not receive even the basic primary

health care services that are necessary for all children and young

women [6]. Kenya National Survey of People with Disability

(KNSPWD) was the first survey of its kind to be conducted in

Kenya. It found that around 4.6% of the population, or 1.7 million

Kenyans, live with a form of disability. More PWDs reside in rural

than in urban areas There is no discrete data for pregnant women

living with a disability [7].

The recommendation of the current UK NICE Antenatal Care

Guidelines is that all pregnant women should access health care

services early. In general, people living with disabilities may face

considerable challenges in accessing health care services. Little

research exists on addressing maternity issues among pregnant

women living with disability focuses on their disability rather

than their reproductive capability [5]. Therefore the aim of this

study was to assess attitudes, feelings and opinions of women

living with disability on their reproductive health in Kakamega

County, Kenya

Literature Review

Demographic factors of both the women living with disability

and able-bodied women have to be considered when looking

at maternal and neonatal health indicators. These included age,

level of education, religious affiliation, number of pregnancy,

occupation status. Pregnant women living with disabilities face

many challenges including stigma, inability to access health care

services, poverty, rejection, and discrimination which change

their perception of their reproductive health in terms of attitude,

opinion, and feelings.

The study by indicated that approximately 7% of women in Rhode

Island reported a disability [8]. Women living with disabilities

reported significant disparities in their health care utilization,

health behaviors, and health status before and during pregnancy

and during the postpartum period. Compared to able-bodied

women, they were significantly more likely to report stressful

life events and medical complications during their most recent

pregnancy, were less likely to receive prenatal care in the first

trimester, and more likely to have preterm births compared to

able-bodied women. As for pregnancy experiences, women

living with disabilities were over twice more likely to report a

health complication during pregnancy compared to able-bodied

women. Women living with disabilities were more likely to

report experiencing stressful life events and physical abuse during

pregnancy, and over twice as likely to report feeling unsafe in

their neighborhood than able-bodied women. Nearly 84% of

able-bodied women received prenatal care in their first trimester,

compared with approximately 78% of WLWD. Women living

with disabilities were nearly twice as likely to begin prenatal care

after their first trimester, and more likely to report inadequate prenatal care and were less likely to report having a postpartum

check-up within six weeks of birth. This may be due to movement

challenges, language barriers, and other in accessibilities. Findings

from this study also suggested that recent WLWD have lower

levels of education, are less likely to be married, and more likely

to be receiving public insurance and have lower household income.

This study also highlights significant disparities in their pre-

pregnancy, pregnancy-related and postpartum health status, health

behaviors, health care utilization, and adverse birth outcomes

between women with and without disabilities. They also reported

higher rates of physical abuse from a current or former partner

during their pregnancy and reported receiving less social support

following delivery. The additional medical complications of

pregnancy among women living with disabilities compounded

by the high levels of financial, partner-related, traumatic, and

emotional stress and the lack of perceived social support could

potentially further compromise their health and the health of

their babies. The delay in accessing health care could be partly

because of the bad experiences of women living with disabilities

with their health care providers. Women with disabilities often

reported that their health care providers are not able to manage

their pregnancies effectively, possess negative stereotypes about

their sexuality, disapprove of their pregnancy, and question their

ability to parenting. These negative and humiliating experiences

with health care providers could potentially prevent women with

disabilities from seeking timely prenatal and postpartum care.

Pre-pregnancy differences in the health of women with disabilities

in this study, including a significantly increased likelihood of

unplanned pregnancy, have implications for clinicians caring for

women with living with disabilities during their childbearing years.

Delayed prenatal care increases the likelihood that these health

problems may result in poor maternal and neonatal outcomes,

including the delayed recovery of women with disabilities during

the postpartum period. The increased likelihood of poor infant

outcomes in women living with disabilities necessitates greater

attention of healthcare providers to the health of women with

disabilities before and during pregnancy.

Findings by indicated that although women living with disabilities

do want to receive institutional maternal healthcare, their

disability often made it difficult for such women to travel to

access skilled health care, as well as gain access to unfriendly

physical health infrastructure [4]. Other related access challenges

include healthcare providers? insensitivity and lack of knowledge

about the maternity care needs of WLWD, negative attitudes of

service providers, the perception from the society that women

with a disability should be asexual and health information that

lacks specificity in terms of addressing the special maternity care

needs of women with disability. This study gives insight into

why WLWD has poor access to health care institutions and their

inability to access professional care.

A study done in Ethiopia found out that ?Maternal healthcare

services that are designed to meet the needs of able-bodied

women might lack the flexibility and responsiveness to meet the

special maternity care needs of women living with disability?.

More disability-related cultural competence and patient-centered

training for healthcare providers as well as the provision of

disability-friendly transport and healthcare facilities and services

are needed.? The findings of this study indicate that despite the

policy for provision for people with disabilities [4]. The health

care institution has not complied with the policy. More so the

health workers have not received sufficient knowledge on the care

of WLWD. This contributes to poor maternal health outcomes.

In a study by a total of 247 women with a disability and 324 age-

matched controls aged 15-45 years were recruited for the study. 87%

of women with disabilities had a physical disability [9]. The mean

age of women with a disability was 29.86 against 29.71 years among

able-bodied women. A significantly lower proportion of WLWD

experienced pregnancy compared to able-bodied women. A higher

proportion of able-bodied women (7.7%) compared to WLWD

(5.3%) reported a successful pregnancy in the past two years. There

were no statistically significant differences between women with

and without a disability with regard to the utilization of antenatal

care and pregnancy outcomes. The proportion that was illiterate

was similar between the two groups. However, a significantly

higher proportion of able-bodied women had been educated to

graduation or beyond, compared to none among WLWD. The

findings suggested that WLWD has poor ANC attendance as a

result of their disability status. Discrimination and stigmatization by

society deny them the chance to have sufficient formal education.

Furthermore, reproductive health experiences differed significantly

between the two groups. A significantly lower proportion of women

with a living disability experienced pregnancy compared to able-

bodied women. Despite this, women living with disabilities had

more living children compared to able-bodied women. There was a

significant difference between the proportions of WLWD reporting

diabetes compared to able-bodied women. In the same study, women

who had delivered a live birth during the past two years were

administered additional questions regarding the last pregnancy.

A higher proportion of able-bodied women compared to WLWD

reported a successful pregnancy in the past two years. Delivery at

hospitals and delivery through the surgical Caesarean section were

common among able-bodied women but these differences were

not statistically significant. WLWD reported less attention during

their pregnancy by health providers compared to peers but these

differences were again not statistically significant. Comorbidities

like convulsions and depression were reported to be significantly

higher among WLWD, though there was no difference in relation

to diabetes and hypertension between the two groups.

A 2004 report by Save the Children Norway found that sexual

abuse of children with disabilities is increasing in Zimbabwe,

and that 87.4 percent of girls with disabilities had been sexually

abused. Approximately 48 percent of these girls were mentally

challenged, 15.7 percent had hearing impairments and 25.3 percent

had visible physical disabilities [10]. As indicated in the study,

WLWD has a tendency to be abused sexually because of their

inability to make an informed decision like the women living

with mental disability, also the physical disability hinders them

from running to safety. Sexual abuse affects one psychologically

therefore may affect the maternal and child health outcomes.

Child deaths in developing countries make the largest contribution

to global mortality in children younger than 5 years. 90% of

deliveries in the poorest quintile of households happen at home.

We postulated that a community-based participatory intervention

could significantly reduce neonatal mortality rate [11].

Prior studies have shown that women living with disabilities are at

greater risk of intimate partner violence (IPV) than the able-bodied

women. A study by found out that women living with disabilities

have a greater risk for all six measured forms of IPV [12].

The findings of the study by show that all WLWD who have had

the experience of giving birth to a child or children faced immense

challenges in childbearing [3]. A participant living with disability

reportedly felt that the inability of healthcare staff to use sign

language was perhaps the cause of the loss of her babies.

?All my babies died because the doctors and nurses could not

use sign language.?

Another participant who was epileptic; it was difficult to travel

from the rural areas where she lived with her grandmother because

she was divorced. The worst was that her husband married an

able-bodied woman in order to frustrate her.

study stated that a great number of refugees living with disabilities

and their caregivers in Kenya and Uganda complained about

challenges to accessing health services [5]. Negative and

disrespectful health provider attitudes were reported as the

most influential barrier that interferes with refugees living with

disabilities from accessing services. In Uganda, negative health

care provider attitudes were a big problem at health centers and the

national referral hospital. An adult male participant with physical,

vision, and mental impairments felt that the health workers think

PWD did not have a right to sex, yet they are normal people like

everyone else. Another refugee with mental impairment stated that

PWD did not receive proper care from nurses and doctors and they

were not treated as human beings. Other reported barriers included

waiting for long on the queues (Kenya and Uganda), costs of

seeking care (Uganda), refugee status (Uganda), communication

with health providers (all three sites), caregiver and community

health workers attitudes (Uganda), lack of transportation (Kenya

and Uganda), and limited accessibility (all three sites). In Uganda,

where all mentioned concerns were raised, refugees living with

disabilities and caregivers listed as barriers to accessing care: the

lack of translation, for both spoken and sign language; lack of

transportation to health facilities; limited wheelchair availability

at the referral hospital; stock-outs of medicines; and lack of money

to pay health workers. This shows that disability on its own is a

major factor on the accessibility and utilization of quality health

care services.

Theoretical Framework

Critical Disability Theory (CDT)

This study was guided by the critical disability theory (CDT) which was propounded by This is an emerging theoretical framework for the study and analysis of disability issues. This theory evolved from the work of scholars who formed the Frankfurt School, a term which refers to a group of Western Marxist social researchers and philosophers originally working in Frankfurt, Germany A Critical theory sees problems of PWDs explicitly as the product of an unequal society [14]. It ties the solutions to social action and change. Notions of disability as social oppression mean that prejudice and discrimination disable and restrict people?s lives much more than impairments do. For example, the problem with public transport is not the inability of some people to walk but that buses are not designed to take wheelchairs. Such a problem can be ?cured? by spending money to ensure that public transport is designed in such a way that it becomes accessible to persons with disabilities. The impact of this critical theory on healthcare and research has tended to be indirect. It has raised political awareness, helped with the collective empowerment of PWDs and publicized their critical views on healthcare. It has criticized the medical control exerted over the lives of PWDs, such as repeated and unnecessary visits to clinics for impairments that do not change and are not illnesses in need of treatment. Finally, it suggests a more appropriate societal framework for providing health services to PWDs This radically different view is called the social model of disability, or social oppression theory. While respecting the value of scientifically based medical research, this approach calls for more research based on social theories of disability if research is to improve the quality of lives of the people with disabilities. The theory views the problems of people with disabilities explicitly as products of an unequal society. The discrimination aspects in the theory helped to explain the experiences of women with physical disabilities in accessing and utilizing healthcare services. This theory finds relevance in the factors that hinder women with physical disabilities from accessing and utilizing health services from public facilities.

Materials and Methods

This was a mixed study design which utilized cross sectional both

descriptive analytical study design and experimental study design

(randomized controlled trial) in 2018 and 2019. The study utilized

both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques. Data

was collected using interview, structured questionnaire and focused

group discussions. The study targeted women living with disability

who are confirmed pregnant. The area of study was Kakamega

County. The target population comprised of pregnant, women

living with disability aged 15 to 49 years in Kakamega County

who are confirmed pregnant in their first or second trimester

preceding the survey A priory sample size calculation was done

using the software G*Power 3.1.9.4 for windows. The results

yielded a 103 total sample size, 54 in the control group and 49 in

the experimental group

The study used a multistage probability sampling design. Simple

random sampling technique to identify the sub counties, stratified

simple random technique to identify urban and rural sub counties

and purposeful and snow balling sampling technique to identify

the pregnant women living with disabilities. Data collection was

by Focus Group Discussions using recorders and pen and note

books to capture what the respondents discuss.

Data analysis

For quantitative data, the data was entered, cleaned, coded and analyzed using SPSS software (statistical package for social sciences) Version 25. Variables were examined through bivariate and multivariate analysis by computing odds ratio at 95% confidence interval. A p-value of ? 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression was applied to determine the relationship between the independent variables that showed significance with outcome variable. During analysis, the researcher omitted those questionnaires without responses on vital information of this study. The researcher conducted analyses of normality, for the outcome variable, prior to hypothesis testing by examining kurtosis and skewness of the data. In order to test and identify possible outliers in the data, graphical assessment visuals, including scatter and box plots were used. Elimination of observed outliers was based on a case by case basis, dependent on standard deviations, and on normality and homogeneity of variance assessments. Normality was assessed using examination of the histograms by seeing how they related or deviate against a normal bell curve distribution and observing the levels of kurtosis and skewness present. Univariate analysis was used to describe the distribution of each of the variables in the study objective; appropriate descriptive analysis was used to generate frequency distributions, tables and pie charts. Bivariate analysis was used to investigate the strength of the association and check differences between the outcome variable and other independent variables. Chi square test of independence at 0.05 level of significance was used to determine if there is a relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and disability status. Data analysis for qualitative data was by content analysis of the four main themes: pregnancy state, care of the pregnancy, society support, government support and way forward and opinion.

Results

The study designed was to identify and examine the challenges faced by women living with disabilities during pregnancy, childbirth and find interventions to bridge the gaps and improve maternal-child health outcomes by use of partnership model intervention in Kakamega County, Kenya. The sample size was a total of 103 WLWD. This chapter provides a detailed description of the results obtained from the data analysis of the survey. Results are described as simple percentages, means, and standard deviations as appropriate depending on the nature of the variable. FGD collected data in terms of the feelings, opinion and way forward of both the pregnant mothers living with disability and the about pregnancy, delivery and postnatal care.

Table 1: Summary of the Research Sample, Assistants and Design| SUBCOUNTY | Lurambi | Mumias West | Shinyalu | Ikolomani | Malava | Lugari | Likuyani | Mumias East | Matungu | Khwisero | Butere | Navakholo | TOTALS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of WLWD | 3 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 10 | 14 | 22 | 103 |

| No. of able bodied women |

2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 22 | 34 |

| No. of CHVS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 24 |

| No. of disability contact persons |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Partnered(p)/ unpatrnered(up) |

P | Up | Up | P | P | Up | Up | P | Up | P | Up | P | 6.6 |

| Number in unpartnered model |

0 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 54 |

| Number in partnered model |

5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 43 | 83 |

| Type of disability- sensory motor |

3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 19 |

| - epilepsy | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 19 |

| - Mental | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 25 |

| - Physical | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 50 |

| - None | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 21 | 34 |

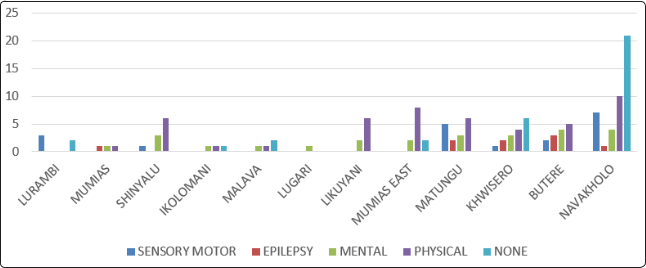

Figure 1: Types of Disability per Sub-County

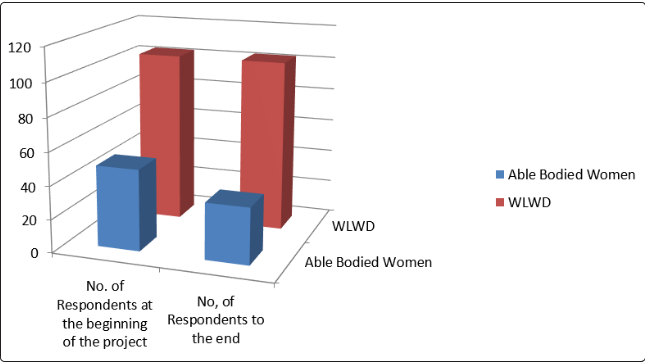

Figure 2: No of Respondents during the Research

Table 1 above showed a summary of the samples, research assistants, and the design used. Six sub-counties were partnered (case) and six which were not partnered (control). In each sub-County, two CHVs and one disability contact person were used as research assistants. Both WLWD and able bodied women were involved in the research as indicated in Fig 2 above. There were 103 WLWD and 34 able-bodied women. 54 of WLWD were not partnered while 83women comprising of 49 WLWD and 34 able-bodied women were partnered. 15 of able-bodied women were not available up to the end of the research giving reasons of being dragged behind by the WLWD, the company of the WLWD being unacceptable because of the culture and others just disappeared without giving any reason. In figure 1 below, of the 103 WLWD, the majority had physical disability 49.5% (51), followed by those who had mental disability 24.2% (25), then 18.4% (19) had a sensory-motor disability and 8.7% (9) had epilepsy.

Table 2: Summary of findings

| N | Able bodied women | WLWD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| No. of respondents at the beginning of the project |

152 | 49 | 32.2% | 103 | 67.8% |

| No. of respondent to the end Pregnancy planned | 137 | 34 | 103 | 75.2 | |

| Pregnancy planned | Yes 20 | 58.8 | 33 | 32 | |

| No 14 | 41.2 | 70 | 68 | ||

| ANC attendance?4visits | 137 | 22 | 64.7% | 61 | 59.2% |

| Child status; | 137 | ||||

| Alive | 34 | 100 | 86 | 85.4 | |

| Lost pregnancy | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.9 | |

| Died at birth | 0 | 0 | 12 | 11.2 | |

| Died postnatally | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Baby congenital abnormalities | 137 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 7.8 |

| Baby Immunized | 137 | Yes 34 | 100 | 100 | 97 |

| No 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Post-natal attendance | 137 | 25 | 73.7 | 56 | 54.9 |

| Place of delivery; | 137 | 34 | 103 | ||

| Hospital | 33 | 2.9 | 98 | 95.1 | |

| Home | 1 | 97.1 | 5 | 4.9 | |

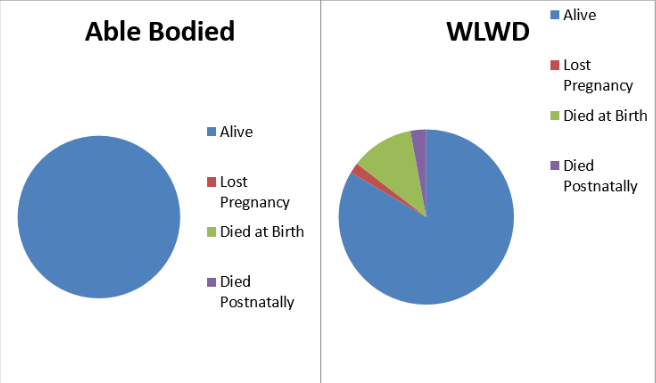

In Table 2 above, it indicates the summary of the study as follow; 17 babies died; 2 were lost pregnancies, 12 died at birth and 3

died during postnatal period. This infant mortality rate if calculate would be 109 deaths per 1000 live birth which was higher than

the worlds 29 deaths per 1000 live births in 2017 All of them were from women living with disability and majority (16 babies) from

unpartnered groups [1]. All the babies of able-bodied women had no complications at birth and six weeks postnatal unlike the babied

of women living with disability who had some forms of complications at the same period. None of the able-bodied women had some

form of congenital abnormalities unlike 7.8% (8) babies born of women living with disability who had some form of complications.

All babies of able bodied women received both polio and BCG immunization unlike 2.9% (3) who had not received any form of

immunization by the time postnatal period was over. Generally postnatal attendance was poor at 73.7% (25) for able bodied women

and 54.9% (56) for women living with disability. Majority of women delivered at the hospital 95.6% and slept under the LLMTN

nets 78.9%. Averagely, a good number received family planning advice 52.5%. Almost all the women delivered in the hospital at

95.6% while only 3.5% (5) delivered at home. Majority had SVD deliveries at 96.9% (131) while only 2.9% (4) had CS deliveries.

The study population was observed from the first trimester up to six weeks after delivery. The findings of study show several

differences between women living with disability and able-bodied women and partnered and unpartnered groups during pregnancy,

childbirth and postnatal.

| Risk factor | N | Disability status | Overall OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able bodied | WLWD | |||||

| Lifetime total pregnancies | ||||||

| <=4 | 125 | 85.3(29) | 93.2(96) | 1.1 | 0.7 - 1.5 | 0.06 |

| 4< | 11 | 14.7(5) | 6.8(7)* | |||

| Was pregnancy planned | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 58.8(20) | 33(34) | 1.8 | 0.6 - 2.2 | <0.001 |

| No | 83 | 41.2(14) | 67(69)* | |||

| Attended antenatal clinic in current pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 104 | 88.2(30) | 71.8(74) | 2.0 | 1.3 - 3.2 | 0.05 |

| No | 33 | 11.8(4) | 28.2(29)* | |||

Major important findings as shown in table 3 above to note were as follows: - able-bodied women were about two times more likely

to have had their pregnancy planned in contrast to the WLWD (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 0.6 - 2.2; p=0.008). Findings of this study suggests

that more able-bodied women than women living with disability attended ANC four times and over at 64.7% (n=22) of the able-

bodied women and 59.2% (n=61) of the disabled women.

Unplanned pregnancy was among the WLWD. In one of the sub-counties, majority said that pregnancies were unplanned and the

reasons were; the husband visited unexpectedly and she would find herself pregnant, another one said that she was raped. Majority

of the women living with disability did not prepare or plan for the pregnancy; some of the women were raped while others just found

themselves pregnant without any plan. In another Sub-County only two out of the seven mothers planned to get pregnant. The rest

had unplanned pregnancies. One of the respondents who was raped refused to talk about how she got pregnant instead she kept on

crying and looking away.

Figure 3 above indicate the child status. 17 babies died; 2 were lost pregnancies, 12 died at birth and 3 died during postnatal period This infant mortality rate if calculate would be 109 deaths per 1000 live birth which was higher than the worlds 29 deaths per 1000 live births in 2017 All of them were from women living with disability and majority (16 babies) from unpartnered groups [1].

The Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Both Pregnant Women Living With Disabilities And Able-Bodied Pregnant Women in Kakamega County, KenyaThis section focuses on the disability status, age, relationship to house hold head, education status, main source of income, marital status, religion, type of housing, pregnancy related demographics and hospital related demographics. This information aimed at getting the demographics of the respondent so that the researcher would get information that was necessary in the carrying out of inferential statistics and in determining possible cause of emerging patterns.

Table 4: Socio-demographic characteristics of Study Participants| Able-bodied | Disabled | ? 2 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcounty | Butere | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | 100.0% | 35.02 | <0.001 |

| Shinyalu | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 100.0% | |||

| Ikolomani | 1 | 33.3% | 2 | 66.7% | |||

| Matungu | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 100.0% | |||

| Mumias east | 2 | 16.7% | 10 | 83.3% | |||

| Mumias west | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 100.0% | |||

| 62.5% | 10 | 37.5% | 6 | Khwisero | |||

| Navakholo | 21 | 48.8% | 22 | 51.2% | |||

| Lurambi | 2 | 40.0% | 3 | 60.0% | |||

| Malava | 2 | 50.0% | 2 | 50.0% | |||

| Likuyani | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 100.0% | |||

| Lugari | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||

| Relationship to the H/Head | Head | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 100.0% | 12.75 | .026 |

| Spouse | 31 | 34.1% | 60 | 65.9% | |||

| child by birth | 3 | 8.6% | 32 | 91.4% | |||

| grand child | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 100.0% | |||

| other children by relationship |

0 | 0.0% | 2 | 100.0% | |||

| house girl | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |||

| Others | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||

| Education status |

None | 0 | 0.0% | 12 | 11.6% | 8.617 | .031 |

| Primary | 25 | 73.5% | 55 | 53.4% | |||

| Secondary | 8 | 23.5% | 22 | 21.4% | |||

| Tertiary | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 4.9% | |||

| N/A | 1 | 3.0% | 9 | 8.7% | |||

Table 4 above is a summary of the socio-demographic variables of the respondents. 75.2% (n=103) of the respondents were WLWD and 60.6% (n=83) were partnered. Proportionally, many respondents were of age category 25-29 years (27.7%, n=38) and were a spouse to the household head (66.4%, n=91). The self- report results showed that many completed primary education (58.4%, n=80) and did not have a main source of income, and they were dependents (47.4%, n=65). A great proportion of the respondents were of indigenous religion (46%, n=63) and about 54.7% (n=75) lived in a semi-permanent house. In marital status, 48.2% (n=66) were in a monogamous marriage while a few were in polygamous marriage (4.4%, n=6).

Chi-square tests showed that there were significant associations

between sub-county ? 2 (11, N=137)35.022, p<0.001 which was

due to the study design. Relationship to Household head ? 2 (5,

N=137) =12.754, within status, the women living with disability

seem to have a distorted family unlike the able-bodied women.

Women living with disability were less educated while some had

no education at all unlike the able-bodied women who at least had

some education. These findings were in line with the findings in

the Focus Group Discussion whereby a respondent stated that;

?Am happy because I have had a problem of epilepsy for a long

time and the community and my family never encouraged me to

get pregnant but unfortunately my husband did not accept my

epileptic condition and now am living with my parents?

To support this notion, another respondent stated that; ?Am happy about this pregnancy but the truth is that was not

ready for this pregnancy. Its unfortunate that due to my epileptic

condition, my husband did not like my seizures, I was chased

away from my matrimonial home and I have difficulties in getting

assistance the community whenever I get seizures?

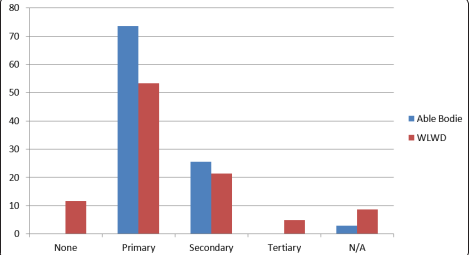

Figure 4: Education Status in Percentage

In figure 4 above showed that able bodied women were more educated than WLWD. All able bodied women had some form of education unlike some WLWD had no form of education and therefore achieved no tertiary education.

Bivariate analysis of pregnancy-related characteristics associated with disability status

Table 5: Pregnancy client characteristics associated with disability state| Risk factor | N | Disability status | Overall OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able bodied | WLWD | |||||

| Lifetime total pregnancies | ||||||

| <=4 | 125 | 85.3(29) | 93.2(96) | 1.1 | 0.7 - 1.5 | 0.06 |

| 4< | 11 | 14.7(5) | 6.8(7)* | |||

| Was pregnancy planned | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 58.8(20) | 33(34) | 1.8 | 0.6 - 2.2 | <0.001 |

| No | 83 | 41.2(14) | 67(69)* | |||

| Attended antenatal clinic in current pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 104 | 88.2(30) | 71.8(74) | 2.0 | 1.3 - 3.2 | 0.05 |

| No | 33 | 11.8(4) | 28.2(29)* | |||

Source: Researcher 2019 *=Reference category

Table 6: Pregnancy client characteristics associated with disability state| Risk factor | N | Disability status | Overall OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able bodied | WLWD | |||||

| Lifetime total pregnancies | ||||||

| <=4 | 125 | 85.3(29) | 93.2(96) | 1.1 | 0.7 - 1.5 | 0.06 |

| 4< | 11 | 14.7(5) | 6.8(7)* | |||

| Was pregnancy planned | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 58.8(20) | 33(34) | 1.8 | 0.6 - 2.2 | <0.001 |

| No | 83 | 41.2(14) | 67(69)* | |||

| Attended antenatal clinic in current pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 104 | 88.2(30) | 71.8(74) | 2.0 | 1.3 - 3.2 | 0.05 |

| No | 33 | 11.8(4) | 28.2(29)* | |||

Bivariate analysis on pregnancy-related client factors that are

associated with disability status shows that there was a borderline

significant relationship between lifetime total pregnancies and

disability status in the study area (OR: 0.7; 95% CI: 0.7 - 1.5;

p=0.06) as shown in Table 5 above. The able-bodied women were

1.1 times more likely to have four children or less compared to

disabled women. Women who confirmed their pregnancy within

two months or less were one-point-three times more likely to

be able-bodied (OR: 1.3; 95% CI: 0.7 - 2.3; p=0.97). The mode

of pregnancy confirmation was not statistically significant with

disability status with the results showing that women who were

able-bodied being one point seven times more likely to have

known they are pregnant through test kits or clinic attendance

compared to their counterparts with disabilities (OR: 1.7; 95% CI:

1.5 - 3.0; p=0.14). Similarly, able-bodied women were about two

times more likely to have had their pregnancy planned in contrast

to the disabled women (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 0.6 - 2.2; p<0.001).

These findings were in line with the group discussion held whereby

majority of the respondents were happy that they were pregnant

though they were not prepared for the pregnancy. It was found out

that most women living with disability desire to be pregnant and have

children although they had unplanned pregnancies. Motherhood is

not only desired by able-bodied women but also the women living

with disability. This was stated below by some of them;Bivariate analysis on pregnancy-related client factors that are

associated with disability status shows that there was a borderline

significant relationship between lifetime total pregnancies and

disability status in the study area (OR: 0.7; 95% CI: 0.7 - 1.5;

p=0.06) as shown in Table 5 above. The able-bodied women were

1.1 times more likely to have four children or less compared to

disabled women. Women who confirmed their pregnancy within

two months or less were one-point-three times more likely to

be able-bodied (OR: 1.3; 95% CI: 0.7 - 2.3; p=0.97). The mode

of pregnancy confirmation was not statistically significant with

disability status with the results showing that women who were

able-bodied being one point seven times more likely to have

known they are pregnant through test kits or clinic attendance

compared to their counterparts with disabilities (OR: 1.7; 95% CI:

1.5 - 3.0; p=0.14). Similarly, able-bodied women were about two

times more likely to have had their pregnancy planned in contrast

to the disabled women (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 0.6 - 2.2; p<0.001).

These findings were in line with the group discussion held whereby

majority of the respondents were happy that they were pregnant

though they were not prepared for the pregnancy. It was found out

that most women living with disability desire to be pregnant and have

children although they had unplanned pregnancies. Motherhood is

not only desired by able-bodied women but also the women living

with disability. This was stated below by some of them;

A Respondent Said

?I have been using family planning for long because my disability

was caused by my first pregnancy that developed complications

but unfortunately, I found myself pregnant?

Another Respondent Stated That

?Am happy about this pregnancy but the truth is I was not ready

for this pregnancy?.

Another Respondent Stated

?Am happy to have my own children though I had not prepared

for this pregnancy?

Another Respondent from Another Sub County Said

?Am happy about the pregnancy but Ihad not planned because I

am a student in form 1?

ANC clinic attendance was significantly associated with the

disability status (P=0.05). Women living with disability had

delayed ANC attendance because their status interfered with

movement to a health facility. They needed someone to escort

them to the clinic because they faced challenges because the means

of transport available was not improvised to meet their disability

status and the terrain wasn?t favorable. One of the respondent in

the Sub-County was completely crippled and needed to be carried

to the health facility to attend which could not afford motorbike

or taxi services

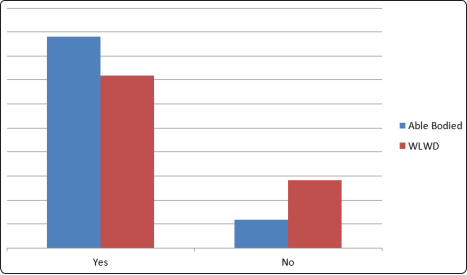

Figure 5: Planned and Unplanned Pregnancy in Percentage

Figure 5 above indicated that more of unplanned pregnancy was among the WLWD. In one of the sub-counties, majority said that pregnancies were unplanned and the reasons were; the husband visited unexpectedly and she would find herself pregnant, another one said that she was raped. Majority of the women living with disability did not prepare or plan for the pregnancy; some of the women were raped while others just found themselves pregnant without any plan. In another Sub-County only two out of the seven mothers planned to get pregnant. The rest had unplanned pregnancies. One of the respondents who was raped refused to talk about how she got pregnant instead she kept on crying and looking away.

Bivariate Analysis of Hospital Related Characteristics Associated With Disability Status

Table 4.5 below presents findings on access to the nearest health facility and reveals a significant relationship between distance to the health facility and disability status. Able- bodied women were 60% more likely to perceive distance to facility to be less than an hour compared to the women with disability (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4- 3.5; p=0.01). Similarly, able bodied women were 20% less likely to use vehicles or boda-boda to the health facility compared to the WLWD (OR: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.7- 1.4; p=0.02). Response of facility provisions for women living with disability was statistically associated with disability status and able-bodied women were almost two times more likely to agree the facility had provisions for women with disability compared to their counterparts (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.7- 1.4; p<0.001). The provisions included ramps and modified coach for the physically challenged. Braille for the blind and sign language interpreter the deaf and dumb.

Table 7: Factors associated with access to health facility and disability status| Risk factor | N | Disability status | Overall OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able bodied | WLWD | |||||

| Distance from home to health facility | ||||||

| <=1 hour | 85 | 61.7(21) | 62.2(64) | 1.6 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 0.01 |

| >1 hour | 52 | 38.3(13) | 37.8(39)* | |||

| Mode of transport to facility | ||||||

| Vehicle/boda- boda |

78 | 76.5(26) | 50.4(52) | 0.8 | 0.7 - 1.4 | 0.02 |

| On foot | 59 | 23.5(8) | 49.5(51)* | |||

| Facility provision for the disabled | ||||||

| Yes | 64 | 73.5(25) | 37.9(39) | 1.6 | 0.7 - 1.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 73 | 26.5(9) | 62.1(64)* | |||

Table 6 above presents findings on access to the nearest health facility and reveals a significant relationship between distance to the health facility and disability status. Able- bodied women were 60% more likely to perceive distance to facility to be less than an hour compared to the women with disability (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4- 3.5; p=0.01). Similarly, able bodied women were 20% less likely to use vehicles or motor cycle (boda boda) to the health facility compared to the WLWD (OR: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.7- 1.4; p=0.02). Response of facility provisions for women living with disability was statistically associated with disability status and able-bodied women were almost two times more likely to agree the facility had provisions for women with disability compared to their counterparts (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.7- 1.4; p<0.001). The provisions included ramps and modified coach for the physically challenged. Braille for the blind and sign language interpreter the deaf and dumb.

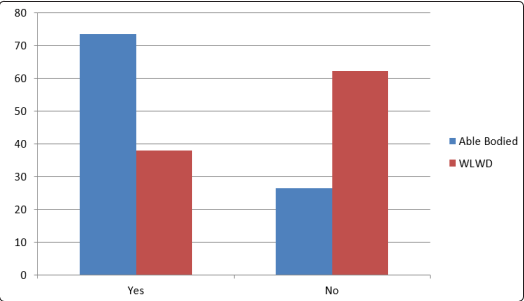

Figure 6: Facility Provision for the Disabled

In figure 6 above, in response of facility provisions for women

living with disability, majority stated that they lack health facility

provision for their status. The provisions included ramps and

modified coach for the physically challenged. Braille for the blind

and sign language interpreter the deaf and dumb.

Determining if Significant Difference Exists in Maternal and

Child Health Outcomes Between Able Bodied and the Women

Living With Disability Before and After Birth

Maternal factors that were observed during pregnancy included;

vaginal bleeding, fits, severe abdominal pains, paleness, Severe

headache, foul smell, any abnormal vaginal discharges, pain while

passing urine, reduced or no kicking by the baby, Blurred vision,

fast or difficulty in breathing, Unusual swelling of the face and

legs, few slept under LLMTN, and had poor nutritional status.

Additional maternal outcomes observed at birth included hand

washing technique, breast feeding technique, any other illness,

advise on family planning, number of ANC visits, any treatment

given during pregnancy, method of delivery, place of delivery

and PNC visit. Child outcome included weight of the baby at

birth, condition of the baby at birth(alive/dead), health status of

the baby at birth, Fever, Fast or difficulty in breathing, inability to

breastfeed, Chest drawn, unconsciousness, unusually sleepiness or

drowsiness, lack of energy or a feeling of weakness, feeling very

cold, redness of the umbilical cord, pus from the umbilical cord,

stiffness of the neck, yellow soles, any congenital abnormalities

detected, any other signs of sickness/ Local infection, Immunization

of BCG and Polio. It also tested the difference of the outcome

between the women living with disability and able bodied women.

Focus Group Discussion

Theme One: Pregnancy State

Feelings about Being Pregnancy

Majority of the respondents were happy that they were pregnant

though they were not prepared for the pregnancy. This shows that

most women living with disability desire to be pregnant and have

children. Motherhood is not only desired by able bodied women

but also the women living with disability. This is as stated below

by some of them;

A Respondent from Butere Said

?Am happy because I have been using family planning for long

because my disability was caused by my first pregnancy that

developed complications?

Another Respondent from Navakholo Stated That

?Am happy about this pregnancy but the truth is that I was not

ready for this pregnancy. It?s unfortunate that due to my epileptic condition, my husband did not like my seizures, I was chased

away from my matrimonial home and I have difficulties in getting

assistance the community whenever I get seizures?

A Respondent from Shinyalu Said

?I am happy to have my own children? another respondent said

?I am happy because where am married, I want them to accept

me and help me in the future.?

A Respondent from Khwisero Stated That

?Am happy because I have had a problem of epilepsy for a long

time and the community and my family never encouraged me to

get pregnant but unfortunately my husband did not accept my

epileptic condition and now am living with my parents?

Another Respondent from Butere Said

?Am happy about the pregnancy but had not planned because I

am a student a Form 1?

One of the respondent who has mental retardation, the mother

in law said that she is happy about the pregnancy because she

is a daughter in law who is giving birth to her grandchildren.

Unfortunately this is her third pregnancy but she is not able to do

anything. The husband on the other side has not been responsible

from the beginning. She said that she is happy because her lineage

has been extended.

In navakholo, one Respondent Said

?I love this pregnancy because it is a way of continuing on God?s

generation?

Planning for the Pregnancy

Most of women living with disability confessed to have had unplanned pregnancy. In Shinyalu majority said that the pregnancy was unplanned and the reasons were; the husband came abruptly, she just found herself pregnant, another one said that she was raped. Some of the women were raped while others just found themselves pregnant without any plan. In Butere Sub County only two out of the seven mothers planned to get pregnant. The rest had unplanned pregnancy.

Consent for the Pregnancy

Some women living with disability were raped, ?Yes I consented but later on my partner disowned the pregnancy? ?yes I consented because all my peer group have children and they use to laugh at me. Now I can walk with my head high?

Hard Moment of a Pregnant Disabled Mother

?The pregnancy has made me poor due to prolonged illness and I keep on accessing medical care?

?My family has loved me more?

?My family did not like my daughter in law?s pregnancy to a point

that they have stigmatized her.?

A respondent from Navakholo said

?A nice moment of this pregnancy was when my mother in law

noticed that I was pregnant and was happy.?

Another respondent said

?There is so much love in the house because of this pregnancy,

I do little house chores?

Some difficult moments of during pregnancy were handling

pregnancy complications, hospital payments, being abandoned

by spouse during pregnancy period and also financial challenges.

A respondent in Navakholo said

?I since I got pregnant, I have had to close my business because

I have a lot of problem with movement and now I don?t have any

income of my own?

Theme Four: Government Support

They all sadly said that the government does not assist them as people living with disability. The health facilities are not disability friendly. They are neglected Deaf respondent from Lurambi said; ?We are not helped because we can?t speak?

Discussion

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

This study established enormous socio demographic difference

between the able-bodied women and women living with disability.

The women living with disability find themselves in health risks

that lead to poor maternal and child health outcomes. These

findings are similar to other studies with profile of high fertility

rate, high infant mortality and low socio-economic status [3]. The

findings in this study indicates that as much as women living with

disability experience challenges, they desire to have children of

their own just like the able bodied women. This was unlike the

findings of a study by that showed that significant low proportion

of women with disability experienced pregnancy (X2 -16.02 P

<0.001) compared to able-bodied women [9]. The self-report

results showed that many completed primary education (58.4%,

n=80). A significantly higher proportion of able-bodied women

were educated up to and including university education and

beyond, compared to the lack of education among women living

with disability (X2- 5.3; p = 0.02) and 11.7%(12) despite the fact

that there was the provision of free primary school education

in Kenya. This is an indication that illiteracy level among the

women living with disability is high and therefore affects their

ability to understand the instruction given in the hospital on how

to take care of themselves during pregnancy. This explains poor

ANC attendance, unplanned pregnancy and also lack of written

birth plan among the majority of them. This was alike findings

whereby about 67% of PWDs had a primary education and 19%

attained secondary education [7]. Few of PWDs had attained

middle level of education, but only 2% had reached university

level [7]. However, this was unlike to where the proportion of

illiteracy was similar between the two groups [9].

Majority of the women living with disability did not have a main

source of income and were dependents. This is due to lack of

financial empowerment to take care of their maternity care needs.

This explains why they are unlikely to use other forms of transport

to go to a health facility apart from going on foot. They lack the money to pay for transport service this was similar to the findings

by a third of people living with disabilities work in their family

business, but a quarter are dependents [7]. As per marital status,

generally the women living with disability had more distorted type

of marriages unlike the able-bodied women. This is an indication

the community is yet to accept women living with disability as

spouses who able to raise families just like the able-bodied women.

They also lack spousal support during pregnancy and delivery

instead they rely on other people for support who may feel that

it is not their full responsibility.

A great proportion of the respondents were of indigenous religion (46%, n=63) unlike the able bodied women which is a sign of desperately looking for the spiritual intervention as a consolation to cure there disability as said by a woman living in in one of the sub counties; ?They are laughing but I am visiting a spiritual healer and I know that I will one day be healed.? It may also point to a high illiteracy levels and not realizing that disability has health causes that are beyond spirituality and curses. These findings were similar to who found out that women living with disabilities in India were younger, less educated, more likely to be unmarried, and have a high household poverty status compared to able bodied women [8].

Pregnancy-Related Characteristics Associated With Disability Status

Pregnancy status was more complex for women living with disability

than able bodied women. Bivariate analyses on pregnancy-related

client factors that are associated with disability status show that

there was a borderline significant relationship between lifetime

total pregnancies and disability status in the study area. The able-

bodied women were 1.1 times more likely to have four children or

less compared to women living with disability. Disability status is

never a reason not to have a family and children. Women living with

disability desire to have a continuity of their own generation. They

wish to bear and raise their own children. Women who confirmed

their pregnancy within two months or less were one-point-three

times more likely to be able-bodied because they had planned for the

pregnancy and were more educated to identify the changes in their

bodies. Able-bodied women were able to confirm their pregnancy

test results. This was one point seven times higher than their counter

parts. This was unlike the women living with disability who only

discovered that they were pregnant by chance; some went to be

treated for other illnesses only for them to be told that they were

pregnant. The mode of pregnancy confirmation was not statistically

significant with disability status. This was similar the findings by

whereby reproductive health experiences between women living

with disability and able bodied women differed significantly [9].

In terms of planning for pregnancy, most of the women living

with disability did not plan for the pregnancy and neither did

they consent. Able-bodied women were about two times more

likely to have had their pregnancy planned. (OR: 1.8; 95%CI:

0.6 - 2.2; p=0.008). Some women living with disability were

raped, some just found themselves pregnant because they were

not on any family planning method and some just discovered

that they were pregnant after a sickness or a visit to the hospital.

There was an indication that the community took advantage of

the sexual life of women living with disability and used them

as sex objects because some like those with mental disability

cannot make informed decision on when, how and with whom to

have sex with. The ones with physical disability have challenged

movement and cannot run away from rapist. The deaf and dump

cannot easily communicate with the rest in the community there

for were unable to report those who rape them. Others felt inferior and hence the men took the advantage and misused them sexually

and finally dumping them when they get pregnant. The ones with

epilepsy were married of to any available man either because of

embarrassment by her family members or the culture which paints

them to be possessed with evil spirit. Where there are married off,

once pregnant, their spouses disowned them and were left helpless.

This agrees with which indicated Pre-pregnancy differences in

the health of women living with disabilities meant an increased

likelihood of unplanned pregnancy [8]. In the FGD, majority of

the respondents living with disability said that though they were

not prepared for the pregnancy, they were happy that they were

pregnant. This shows that most women living with disability

desire to be pregnant and have children. Motherhood is not only

desired by able-bodied women but also by women living with

disability. This study was similar to the findings of which showed

that participants who had not had any childbearing experiences

at the time of the study, wanted to have their own biological

children [15]. For example, a respondent who was 22 years old

with intellectual impairment, and lived in a mental hospital, said

that she wished to have a boyfriend and have children with him.

Hospital Related Characteristics Associated With Disability Status

There was delayed accessibility to the health facility by women

living with disability unlike able bodied women. Findings on

access to the nearest health facility reveal a significant relationship

between distance to the health facility and disability status. Able

bodied women were 60% more likely to perceive distance to

facility to be less than an hour compared to the women with

disability. This is partly because of their disability status: physical

impairment, for the blind the need of a walking stick or someone

to direct her and many other barrier challenges. Similarly, able

bodied women were 20% less likely to use vehicles or motorbikes

to the health facility compared to the disabled women. High level

of poverty amongst them made it impossible to pay for the public

vehicles or motorbikes. They are also not modified to meet the

needs according to their disability. This was noted during FGD

where by a respondent said; ?since I got pregnant, I have a lot of

problem with movement.?

Findings by suggested that although women living with disability

do want to receive institutional maternal healthcare, their disability

often made it difficult for such women to travel to access skilled

care [4]. He also found out that it was common practice for women

with disability living in rural areas to walk to health facilities.

In some cases, they were carried to health facilities when there

were no vehicles available to transport them due to the difficult

terrain and poor roads. Traveling was a major challenge because

it was costly and time-consuming to transport people living with

disability to health facilities generally and it was even more costly

when an additional person was required to accompany them.

A 35-year-old woman with physical disability said ?I had gone for

check-ups in good time so I didn?t wait but I had to walk for half

an hour to reach there for ANC check-ups??. I gave birth to all

my babies at home since I didn?t have money to rent a vehicle.?

The finding was also similar to where most respondents reported

that the reason for their home delivery is due to poor terrain and

transportation expenses.

Response of facility provisions for women living with disability

was statistically associated with disability status; able-bodied

women were almost two times more likely to agree that the facility

had provisions for women living with disability compared to their

counterparts. Despite the policy of provision for people living with disability in all public places in Kenya, the government has

not done much to implement this policy. The health facilities

lack ramps for those with physical impaired, braille for the blind,

sign language interpreter for the deaf and dump and many others.

This affects utilization of these facilities by the women living

with disability and therefore puts them at risk for poor maternal

and child health outcomes. These findings are consistent with

the findings by that found out that although women living with

disability do want to receive institutional maternal healthcare, their

disability often made it difficult for such women to travel to access

skilled care, as well as gain access to unfriendly physical health

infrastructure. In this study, some respondent showed satisfaction

with specific hospital provisions like the Kakamega County referral

Hospital. During FGD, one respondent said ?Government hospitals

are cheaper, I don?t like TBAs. In the Kakamega county referral

hospital, nurses and doctors are qualified to handle pregnancy.

One nurse knows sign language and hospital deliveries are free,

TBAs are unqualified.?

If government implements the disability policy and provide disability provisions in the hospitals, it will tremendously reduce health risks to the women living with disability and that of their children. However, a study by found out that a greater number of refugees living with disabilities and their caregivers in Kenya complained about challenges to access health services [5]. Negative and disrespectful provider attitudes were reported as the most influential barrier that deterred refugees living with disabilities from accessing services. In Kenya, one Somali caregiver, explained, ?In hospitals, we face a lot of pressure?. It was also similar to a study in Ethiopia by who found out that ?Maternal healthcare services that are designed to address the needs of able-bodied women might lack the flexibility and responsiveness to meet the special maternity care needs of women living with disability?[4]. More disability- related cultural competence and patient-centered training for healthcare providers as well as the provision of disability-friendly transport, healthcare facilities and services are needed.? in his study conducted in Ethiopia, also found out that the popular cultural believes of disability, which associates disability with evil spirits, taboos and witchcraft, may be taken into contemporary reproductive healthcare Centres by staff, as culture, gender and disability intersect to frame the discrimination against women with disability [15]. A key discussion in FGD indicated that disability is a social issue in which standard practices in society fail to embrace disability as human diversity, but instead interprets disability to a category of inferiority. In a discussion in a local Kenya Radio Maisha discussion on February 7th 2017 at 12:37 it was noted that in 2013, health functions were devolved to Kenya?s 47 counties, which were bound by the 2010 constitution to implement health policies developed at the national level, including free maternity services. But human rights activists say those services have not been adapted for women living with disability, partly because the government is not gathering information on them

Focus Group Discussion

Pregnant women with disability experience vast challenges during

pregnancy. Majority of the respondents were happy that they

were pregnant though they were not prepared for the pregnancy.

This shows that most women living with disability desire to be

pregnant and have children. Motherhood is not only desired by

able bodied women but also the women living with disability.

This study is alike the findings of showed that participants who

had not had any childbearing experiences at the time of the study,

wanted to have their own biological children [15]. For example,

Vimbai who was 22 years old has intellectual impairment, and she

lives in a mental healthcare institution in an urban area. She has never married, has no children and she is formally unemployed.

She recounted that she wishes to have a boyfriend and to have

children with him.

In terms of planning for pregnancy, most of the women living with

disability did not plan for the pregnancy neither they didn?t consent

for the pregnancy. Some women living with disability were raped,

some just found themselves pregnant because they were not in

any family planning method and some just discovered that they

were pregnant after a sickness or a visit to the hospital. This is

alike which indicated Pre-pregnancy differences in the health of

women living with disabilities which included a significantly an

increased likelihood of unplanned pregnancy [8].

Pregnant women living with disability have had hard moments

and nice moments just like the able bodied pregnant women. Some

of the nice moments were that the love in the family increased,

some were assisted in their house chores and they found happiness

of motherhood.

Some of the hard moments included pregnancy related

sickness, lack of finances needed to take care of the pregnancy,

stigmatization from family members due to her disability status,

difficulty in accessing healthcare facilities and being abandoned

by spouse during pregnancy period. This findings were alike

where by women living with disabilities compared to their able

bodied peers were more likely to report medical complications

and stressful life events during pregnancy [8]. In addition women

living with disabilities were at greater risk of stressful life events

during their pregnancy. Also study done in Ethiopia found out

that ?Maternal healthcare services that are designed to address

the needs of able-bodied women might lack the flexibility and

responsiveness to meet the special maternity care needs of women

with disability?. More disability-related cultural competence and

patient-centred training for healthcare providers as well as the

provision of disability-friendly transport and healthcare facilities

and services are needed.? [4].

Study found out that despite positive feedback, a greater number

of refugees living with disabilities and their caregivers in Kenya

and, especially, Uganda complained about challenges to accessing

health services [5]. Negative and disrespectful provider attitudes

were reported as the most influential barrier that deterred refugees

with disabilities from accessing services. In Kenya, one Somali

caregiver, explained, ?In hospitals, we face a lot of pressure.

They reported the importance of ANC attendance as;-to know

their status, to know the position of the baby to avoid infection

This study is alike whereby women living with disabilities were

more likely to delay prenatal care until after the first trimester,

report inadequate prenatal care, and were less likely to report

having a postpartum check-up within six weeks of birth [8]. The

delay in accessing health care could be partly attributed to the

negative experiences of women with disabilities with their health

care providers.

Most of the respondents did not have birth plans which included

preparation in terms of babies clothes, place of delivery, transport

to the hospital, an assistant during pregnancy and delivery and

financial preparation in fact majority of them didn?t know about

birth plans. The few who had done a bit of preparations would

just include baby?s clothes.

When asked who assist you in care for this pregnancy, Most of

them confirmed to be assisted by their parents. This is an indication of lack of spouse support during pregnancy and delivery of people

living with disability.

All of them are planning to deliver in the hospital whoever none

is ready to deliver in a private hospital; they will deliver in a

government hospital because some say it is affordable and some

say they are free. Other reasons for hospital deliveries are;- bad

obstetric history in previous pregnancy, hard labor, they don?t like

traditional birth attendants because they are unqualified, nurses and

doctors are qualified to handle pregnancy, in Kakamega County

referral hospital, one nurse knows sign language, will get help in

the hospital and some said that their child would get immunized

immediately if delivered in the hospital?

When asked about the society support, majority of the respondent

were assisted by other people rather than their spouses. These

other people are mother in laws, mothers and even fathers. The

reasons they gave for lack of societal support were as follows;-

their disability status, they believe that they give birth to beautiful

children than them than the able bodied women, The spouse and

the community did not like the fact that they got pregnant and

the community does not support because they don?t expect them

to get pregnant. The few time the respondent got support was on

assistance on the house chores like fetching water.

Mako?s narrative also shows that the popular cultural understanding

of disability, which associates disability with evil spirits, taboos

and witchcraft, may be taken into contemporary reproductive

healthcare facilities by staff, as culture, gender and disability

intersect to frame the discrimination against women with disability.

This creates a need of disability training and awareness creation

which reduces the negative impact of traditional practices on the

health and well-being of women with disability. A key argument

of FDS is that? disability is a social construction in which standard

practices in society fail to embrace disability as human diversity,

but instead relegate disability to a category of inferiority [15].

Pregnant women living with disability said that the government

does not help them. Government includes government healthcare

providers and government organisations. They were mostly

neglected because of their disability status which limit them in

accessing government aide for example they said the deaf couldn?t

talk to express their need. This was in line with study stated that

?Despite positive feedback, a greater number of refugees living

with disabilities and their caregivers in Kenya and, especially,

Uganda complained about challenges to accessing health services

[5]. Negative and disrespectful provider attitudes were reported as

the most influential barrier that deterred refugees with disabilities

from accessing services also.? The belief of most people is that

every person should be able bodied, thereby viewing disabled

people as ?damaged beings? who are generally ignored and treated

as sub-standard. The narration indicates an attitude of healthcare

staff which seeks to deny women living with disability space in

reproductive healthcare, on the grounds of the woman?s disability

status and are hence an inconvenience noted by Belaynesh FGD,

a number of healthcare providers assume that people living with

disability are sick persons who should only consult healthcare

centres for issues relating to disability also studied women living

with disability and reported less attention during their pregnancy

by health personnel compared to peers without who are able

bodied [15] [9].

Conclusion and Recommendation

The study found out that disabled women experience a lot of

challenges in maternity care. Their opinion is that they are neglected because of their disability status. They also feel discriminated by

their spouses, community they live in, the healthcare facility and

health care provider during pregnancy, child birth and delivery.

There is a need of programs on awareness of disability issues

in community, family and spouse in order to reduce stigma and

increase acceptance of women living with disability. This will

create positive energy in them to assist these women to feel

accepted and seek positive assistance during pregnancy and

delivery. Health professions should be trained on handling women

living with various disabilities in order to appropriately assist

pregnant women living with disability [16-27].

References

1. World Health Organization (2018) Proportion of births

attended by a skilled health worker. Geneva, Switzerland.

2. Kenya National Bureau of Statistic (2014) Kenya demographic

and health Survey2013-014 report Calverton, Maryland, USA.

3. Christine Peta (2017) Disability is not asexuality: the

childbearing experiences and aspirations of women with

disability in Zimbabwe An international journal on sexual

and reproductive health and rights, Disability and sexuality:

claiming sexual and reproductive rightspg 25: 10-19.

4. John Kuumuori Ganle, EasmonOtupiri, Bernard Obeng,

Anthony KwakuEdusie, Augustine Ankomah, Richard

Adanu (2016) Challenges Women with Disability Face in

Accessing and Using Maternal Healthcare Services in Ghana:

A Qualitative Study Published 11: e0158361.

5. Maggie Redshaw, ReemMalouf, Haiyan Gao, Ron Gray

(2013) Women with disability: the experience of maternity

care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal

period. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13: 174.

6. NGO Shadow Report (2012) United Nations Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,

Frauen:Rechtejetzt! NGO Forum for the implementation of

CEDAW in Austria 1-11.