Author(s): Fatma Aboul-Enein*, Yosra Turkistani, Osama Barnawi, Mohammad Haqash, Zeyad Bukhary, Mohannad Al-Hazmi, Khalid Qashqari Fatimah Al-Ghabban and Najeeb Jaha

Performance of Hajj is physically very demanding, especially if performed during the summer season. The aim of this study is to evaluate the importance of ambient temperature and dehydration, indicated by plasma osmolarity on the clinical outcomes of cardiac patients during Hajj season in 2017

Annually, millions of Muslims travel from over 180 different countries to Makkah city for Hajj; from 8 to 13 of Dhual-Hijja. The lunar calendar only has 354days, compared with 365days for Gregorian calendar, this means that the Hajj is held during different periods of seasonality [1]. Starting 2016 Hajj has entered into the summer months with ambient temperature between 43°C and 48.7°C, and relative humidity of 58-87%, which increases the risk of dehydration [2]. Performance of Hajj is physically very demanding, with extraordinary physical stressors such as heat exposure, dehydration, crowding, and physical exertion, which expose the pilgrims to many health hazards. Most of pilgrims are over the age of 60 years with the cardiovascular diseases being the leading cause of death. The risk of dehydration in older adults is increased because of loss of muscle mass, decreased kidney function, physical and cognitive impairments, reduced thirst and multiple drugs use [3].

Plasma osmolarity has been shown to be a simple and valid tool for assessing dehydration [4]. It reflects the number of dissolved particles per litter of plasma. Plasma osmolarity of 275 to <; 295 mOsmol/L is considered normal; 295 to 300 mOsmol/L suggests impending water loss dehydration; and > 300 mOsmol/L suggests current water loss dehydration [5].

A recent meta- analysis demonstrated increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalization 2.2% with heat wave exposure [6]. Furthermore, several recent studies have demonstrated a significant prognostic role of hyper-osmolarity in patients with acute coronary syndromes and heart failure [7-9].

King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC) is the tertiary cardiac center for cardiac catheterizations and open-heart surgeries in Makkah. In this study, we evaluated the importance of plasma osmolarity on cardiovascular complications, length of stay, and mortality in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients admitted during Hajj season of 2017 (1438 H). This could play a strategic role in managing cardiac patients during Hajj in the coming decade where Hajj will be in the summer time.

Aim is to study the relationship between plasma osmolarity and ambient temperature with cardiovascular clinical outcomes including in-hospital mortality; defined as death during hospitalization; and MACE: defined as any cardiac complication: pulmonary edema, cardiogenic shock, intubation /ventilation, cardiac arrest, readmission, LV thrombus, and LVEF <30%.

This is a retrospective cohort Single center study. All ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients referred to the KAMC Cardiac Center during Hajj of 2017 (1438 H) were included. After local KAMC IRB approval, electronic medical records of included patients were reviewed. The authors attest they have no conflict of interest statement and have not received any funding nor grants.

Plasma Osmolarity which has been calculated from the formula (2 x (Na + K)) + (BUN / 2.8) + (glucose / 18) [10]. Heat index (HI) calculated by the formula: (12) HI = 0.5 *(T + 61.0 + [(T68.0)*1.2] + (RH*0.094)) Using website; http://www.wpc.ncep. noaa.gov/html/heatindex.shtml (T) is the air temperature and (rh) is the relative humidity. Daily temperatures were collected from Saudi general authority of meteorology and environment protection website; https://www.pme.gov.sa/ar/Pages/default.aspx.

Assumption of (α = 0.05) 2-sided, (β = 0.2), mean difference in plasma osmolarity between dying and living patients 10 mOsmol/L. SD = 10, mortality of 5%. Using online sample size calculator; http://www.sample-size.net/. Based on this assumption we needed records of at least 170 patients.

Using SPSS version 26. student’s t-test and Chi square test, used in continuous and categorical variables respectively. Cox regression analysis was used for survival analysis. All tests were two sided, and a significance level of 5% was used.

300 consecutive patients admitted to KAMC cardiac center with STEMI. They were divided into 2 groups according to their plasma osmolarity level, Group (Gp) I patients with plasma osmolarity level <295 mOsmol/L (n= 161), and Gp II patients with plasma osmolarity level ≥295 mOsmol/L (n= 139).

The mean age of study group was 56.2 +/-12.1, 84% were males, with a mean BMI 27.9 ± 5.4 exposed to average ambient temperature on admission days as follows: maximum temperature of 42.5± 3.1 °C and a minimum temperature of 30.3 ± 2.5 °C resulting in Heat index (HI) of 61.9 ± 10.6°C. They have an average plasma osmolarity of 295.1 ±8.7. The majority, 127 (43.2%) were referred for anterior STEMI. The baseline risk factors, characteristics, presentation and complication among both groups are summarized in Table I. A total 13 in-hospital deaths occurred (4.3 %) while 77 (25.8 %) suffered MACE. There was no statistically significance difference between both groups as regard age, gender, BMI, smoking, HTN, being resident, or pilgrim but Group II were more frequently Diabetics (P = 0.046) and history of kidney disease (P = 0.027).

| Total | Gp I (n= 161) |

Gp II (n= 139) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 252 (84 %) | 133 (82.6%) | 119 (85.6%) | 0.48 |

| Diabetes | 147 (49%) | 70 (43.5%) | 77 (55.4%) | 0.04* |

| CKD | 20 (6.7%) | 6 (3.7%) | 14 (10.2%) | 0.028* |

| Hypertension | 164 (54.7%) | 84 (51.5%) | 80 (58.4%) | 0.32 |

| Known CAD | 72 (24%) | 33 (20%) | 39 (28.1%) | 0.13 |

| Smoker | 99 (33 %) | 53 (32.5%) | 46 (33.6%) | 0.49 |

| Pilgrims | 103 (34.3 %) | 60 (37.3%) | 43 (30.1%) | 0.25 |

| Age | 56.2±12.1 | 55.5 ±12.8 | 57.1 ±11.1 | 0.27 |

| BMI | 27.9± 5.4 | 28.1 ±5.3 | 27.6 ±5.5 | 0.42 |

| Heat index | 61.9±10.6 | 61.3 ±10.9 | 62.6 ±10.3 | 0.314 |

| MPV | 10.5±1.3 | 10.4± 1.1 | 10.6 ±1.5 | 0.088 |

| Glucose | 171.4±65.9 | 158.3 ±50.2 | 186.7± 77.8 | <0.001 |

| Sodium | 135.8 ±4.2 | 133.7 ±3.3 | 138.1 ±3.8 | <0.001 |

| Potassium | 4.2± 0.52 | 4.2± 0.5 | 4.2± 0.5 | 0.97 |

| BUN | 17.5± 9.4 | 15.5 ±7.5 | 19.9± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Urea | 6.3 ±3.4 | 5.5 ±2.7 | 7.1± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Osmolarity | 295.1 ±8.7 | 289.2 ±4.4 | 302.0 ±7.3 | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 43.8 ±10.1 | 43.5 ±9.3 | 44.1 ±10.9 | 0.65 |

| cardiac arrest | 16 ( 5.3 %) | 7(4.3%) | 9(6.6%) | 0.668 |

| LOS (days) | 5.2 ±10.7 | 4.01 ± 4.5 | 6.7 ±14.9 | 0.045* |

| LV thrombus | 7 (2.3%) | 3(1.8%) | 6(4.4%) | 0.210 |

| Readmission rate | 5 ( 1.7%) | 2(1.2%) | 3(2.2%) | 0.531 |

| LVEF <30% | 41 (13.7%) | 19 (11.8%) | 22 (15.8 %) | 0.31 |

| MACE | 77 (25.8) | 37(23%) | 40 (29%) | 0.24 |

| In-hospital death | 13 (4.3%) | 3 (1.9%) | 10 (7.2%) | 0.023* |

| BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction; LV: left ventricle; LOS: length of stay; MACE: major adverse cardiac events | ||||

However, comparing Pilgrims and residents is summarized in Table II, pilgrims were older, less frequently male gender and diabetic, they were exposed to a higher heat index 58.4± 9.7 versus 68.5± 9.02, p <0.01. However, there was no significant difference regarding plasma osmolarity, or patient outcomes (mortality or MACE).

| Variable | Residents (N=197) |

Pilgrims (N=103) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 175 (88.8%) | 77(74.8%) | 0.02* |

| DM | 107 (54.3%) | 40 (38.8%) | 0.011* |

| CKD | 12 (6.1%) | 8 (7.8%) | 0.58 |

| HTN | 108 (54.8%) | 56 (54.4%) | 0.94 |

| Known CAD | 57 (28.9%) | 15 (14.6%) | 0.06 |

| Smoker | 53 (32.5%) | 46 (33.6%) | 0.499 |

| Anterior STEMI | 120(60.9%) | 53 (51.5%) | 0.115 |

| Osmolarity >295 | 96 (48.7%) | 43 (41.7%) | 0.249 |

| Age | 54.3 ±12.8 | 59.7 ±9.8 | 0.266 |

| Heat Index | 58.4± 9.7 | 68.5± 9.02 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 28.2±5.3 | 27.3 ±5.3 | 0.181 |

| MPV | 10.4± 1.2 | 10.7 ±1.6 | 0.298 |

| Glucose | 175.8 ±63.8 | 163.1± 69.3 | 0.298 |

| Sodium | 135.7 ±3.9 | 135.9 ±4.6 | 0.755 |

| potassium | 4.2± 0.5 | 4.2± 0.56 | 0.76 |

| BUN | 17.3 ±9.5 | 17.8 ± 9.2 | 0.724 |

| Urea | 6.2 ±3.4 | 6.3± 3.3 | 0.724 |

| osmolarity | 295.0±7.7 | 295.3 ± 10.4 | 0.764 |

| In mortality | 6 (3.0%) | 7 (6.8%) | 0.13 |

| LVEF <30% | 25 (12.7%) | 16 (15.5%) | 0.49 |

| MACE | 44 (22.3%) | 23 (22.3%) | 0.99 |

| BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; MACE major adverse cardiac events | |||

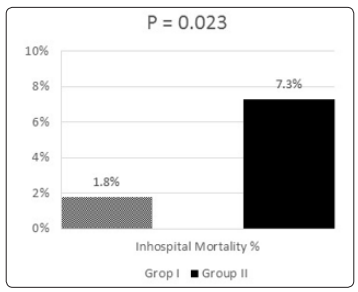

There was no significant difference between the groups regarding cardiac complications; or any MACE. However, Group II had significantly longer length of stay 4.01 ± 4.5 day versus 6.7 ±14.9 p=0.045. A total 13 in hospital death occurred (4.3 %), In hospital mortality was significantly higher in group II 10 (7.2%) versus 3 (1.9%); p = 00.023, Figure 1.

Figure 1: In-Hospital Mortality Rate between the Two Groups

Binary regression model was used for predicting in hospital mortality and MACE is summarized in Table III. We started with univariate model analysis with plasma osmolarity as continuous variable. Then the effect of potential demographic and clinical confounders used univariate models. The independent predictors for mortality are Pilgrim, HI, and plasma osmolarity; conversely HI, was the only independent predictor for MACE.

| Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I.for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| DEATH | HI | .055 | .949 | .915 | .984 |

| Osmolarity GP | .009 | .175 | .047 | .650 | |

| Age | .143 | 1.029 | .990 | 1.070 | |

| PILGRIM | .005 | 0213 | .072 | .631 | |

| MACE | HI | .001 | .974 | .959 | .990 |

| Osmolarity GP | .113 | .660 | .395 | 1.103 | |

| Age | .056 | 1.017 | 1.000 | 1.035 | |

| PILGRIM | .309 | .769 | .464 | 1.275 | |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analysis to establish a link between heat index, osmolarity imbalance and mortality in patients admitted with STEMI.

Makkah, the holiest of Muslim cities, located in the Sirāt Mountains, inland from the Red Sea coast. All devout Muslims attempt a hajj (pilgrimage) at least once in their lifetime [11,12]. Meckkah is 909 feet (277 metres) above sea level in western Saudi Arabia between the dry beds of the Wadi Ibrāhīm and is surrounded by the Mountains. Less than 5 inches (130 mm) of rainfall occur yearly, mainly in the winter months. Ambient temperatures are high throughout the year and in summer may reach 120 °F (49 °C) resulting in a very high heat index [13,14].

In a questionnaire of 412 male; age 43.48±13.42 years pilgrims regarding heat stress awareness in Hajj in 1436 (September 2015) 36% of pilgrims were not aware of Makkah weather; highlighting the importance pilgrims health education on heat-related health issues and coping strategies [14]. In Hajj, activity is unavoidable in high heat index conditions, this emphasizes the importance of public awareness to minimize health risks. Pre-training to provide acclimatization for at least two weeks before hand, liberal intake of fluids before thirst begins and dressing in clothes, including hats, appropriate for the climate is of utmost importance [15]. Nowadays majority of pilgrims reach Makkah by air and arrive within, a few hours of leaving home; giving them little time to acclimatize [16]. Failure to adapt to the high load of ambient temperature can result in heat stress. Exhaustion syndromes may not be accompanied by a rise in body temperature. Several variable affect the heat adaptation namely fatigue , lack of sleep , dehydration, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, lack of acclimatization, all of which are common in Hajj [16].

Our results demonstrate the heat stress is a predictor for MACE, furthermore we demonstrated that Pilgrims are exposed, on admission, to significantly (17%) higher heat index, which is an important predictor factor for in-hospital mortality and MACE.

To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate the effect of heat stress, using heat index, in Saudi Arabia during Hajj season. Recently, several studies from different continents and countries have studied the association of ambient temperature on emergency room visits, admissions with acute coronary syndromes, and mortality [17-23].

In a metanalysis of 18 studies, Bhaskaran et al concluded that there is a statistically significant association between higher temperatures and risk of myocardial infarction, with the main effects up to 3 days later [24]. In 2019, Cheng et al reported a metanalysis on 54 studies from 20 countries to study the global effect of heatwave on cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity and mortality outcomes. They concluded that heatwaves increase the risk of cardiorespiratory mortalities especially in vulnerable subgroups elderly and those with history of ischemic heart disease, In 2012 Bhaskaran et all studied the relationship between hourly temperature in 11 areas in Wales and England and concluded that ambient temperature above a threshold of 20°C , each 1°C increase in temperature was associated with a 1.9% transient increase in risk of myocardial infarction in the following 1-6 hours [24,25].

The adverse physiologic effect of heat exposure was demonstrated in a study by Keatinge et al, on volunteers under controlled conditions of moving air at 41°C for six hours. This caused a 0.84°C rise of core temperature and resulted in increase in red blood cell counts, platelet counts, and blood viscosity, as well as heart rate [26]. A recent study in healthy men age > 55 years, for each 5°C increase in mean ambient temperature HDL decreased -1.76% and LDL increased by 1.74% [27].

Several studies of age-related cardiovascular heat strain have demonstrated that healthy aging is accompanied by altered cardiovascular function, limiting the extent to which older individuals can maintain stroke volume, increase cardiac output, and increase skin blood flow when exposed to heat. This in more prominent in elderly, whereby the increased cardiovascular demand is often fatal due to increased strain on an already compromised left ventricle [28,29].

Previous studies are in agreement with our current study whereby heat index; takes in account the ambient temperature and humidity to construct a scale that describes how warm the air feels. it is easily calculated from available weather website. HI on the day of admission was a predictor of in-hospital mortality and MACE. This underscores the importance of health education to the general public and Pilgrims in specific. In 2008, Noweir et al, studied the climatic heat load in Hajj locations and reported that the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT); a measure of the heat stress, that includes temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle and solar radiation. They reported that WBGT were considerably high for safe heat exposure and that it exceeded the recommended comfort zone [30]. This is in agreement with our results where the average heat index is in the danger zone and was found to be a predictor of mortality and MACE in our population study [31]. Lastly, seasonal variations in blood pressure, serum lipids, and fibrinogen have been observed and may explain the relation between temperature and cardiovascular disease mortality [32]. These data and our study underscores the importance of ambient temperature and consequently cellular dehydration on prognosis.

Dehydration is defined as water-loss, it usually is a result of insufficient fluid intake, resulting in elevation of serum osmolality [33]. Osmolarity is defined as the number of milliosmoles of the solutes per liter of solution. Calculated serum osmolarity (mOsm/L); an estimation of the osmolar concentration of serum; has been recommended as an easy and simple tool to assess dehydration [33]. A study on healthy adults from 3 European counties, showed inadequate hydration status on several days per week, which may have a negative health and cognitive impact on daily life [34].

Water balance inside the body is of vital importance for patients who are critically ill, and serum osmolarity plays an important role in extracellular and intracellular water distribution. Several recent studies have reported the role of hyperosmolarity with increased mortality and readmission in critically ill cardiac patients, heart failure, and in acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous cardiac intervention [7,35,36]. Our results reveal that hyperosmolarity is associated with increased hospital mortality of patients who presented with acute STEMI.

Hyperosmolarity is a result of increase of its components, namely sodium and glucose each of which have been reported as risk factors for adverse outcomes [37,38]. Secondly, hyperosmolarity causes redistribution of body fluids, increasing cardiac preload volume and consequently patient outcomes [35].

Several recent studies have demonstrated that hyperosmotic stress is related to several pathologies [39-43]. Dehydration, and consequent intracellular hyperosmolarity, is a major challenge; as it results in disturbance of global cellular function and cell death [44]. Increased extracellular osmolarity is cytotoxic, it promotes water flux out of the cell, triggering cell shrinkage, and intracellular dehydration, triggering apoptosis, or cell death [42,43]. This adversely affect protein structure and function and altered enzyme activity; it triggers oxidative stress, protein carbonylation, mitochondrial depolarization, DNA damage, and cell cycle arrest, resulting in apoptosis [45].

Exposure of the myocytes to hypertonic media causes NF- κ B (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) and caspase activation through reactive oxygen species (ROS ) production Studies have suggested that the hyperosmotic stress triggers oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species generation within the cells [40,46]. Furthermore hyperosmotic stress triggers apoptosis in cardiac myocytes through a p53-dependent manner [43]. Lastly, when exposed to hyperosmolarity cardio-myocytes exhibit an increase in Aldose reductase (AR) expression that was accompanied by AR-mediated activation of apoptotic signaling pathways [47].

Whenever activity is unavoidable in high heat index conditions (as in Hajj), health education can help minimize health risks. Pretraining to provide acclimatization for at least two weeks before the event [16]. Adaptation strategies, as educating pilgrims on Makkah climate, liberal intake of fluids before thirst begins and dressing in clothes, including hats, appropriate for the climate is of utmost importance to reduce the health effects of heat stress [16]. Moreover, alerting first responders and emergency room physicians to the importance of early intravenous fluid hydration, whenever clinically possible. Physicians should be alerted to the role of plasma osmolarity, at admission, on patient outcome and the possible preventive role of intravenous infusion of normal saline or half normal saline to improve outcome. These data and our study underscores the importance of ambient temperature and consequently cellular dehydration on prognosis.

Firstly, only in-hospital patients and in-hospital complications were recorded. Secondly, this is a retrospective study, with its inherent limitations, conducted in Makkah; hence, the present findings may not be readily extrapolated to other populations or settings. Thirdly, our analysis is restricted to patients admitted to an interventional cardiology center, which may induce selection bias: STEMI cases managed solely medically were not included. Lastly, in the present study, osmolarity was calculated rather than being measured directly, which may be different from actual osmolarity.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, ornot-for-profit sectors.