Author(s): <p>Francesco Mercadante</p>

Thanks to widely used neuroimaging techniques, it is now known that alterations in the cerebral cortex cause speech and thought processing difficulties in individuals with schizophrenia. These difficulties are clearly increased by the dysfunction found in dopamine markers and in glutamate transmission, so that the schizophrenic's speech is described as tangential, illogical and incoherent and most scientists believe that it is based on the deprivation of logical-argumentative connections. While it is true that narrative-conceptual disorganization is irrefutable, it is equally true, however, that by reexamining schizophrenic semantics according to an organic and systemic criterion, it is possible to demonstrate that their linguistic code, besides being accessible, possesses certain precise characteristics: contradiction, metonymic identification between narrator-identity and object-entity, and anaphoric recovery. Even if these characteristics are not sufficient to generate a profile of linguistic cooperation, the analyst can use them to delimit the patient's dimension. Therefore, we aim to show that the linguistic sign is not at all devoid of transparency, as people often say: it must be interpreted systemically and phenomenologically, not according to common expectation.

Undoubtedly, as Bordier, Nicolini and Bifone have pointed out, the decrease in brain parenchyma and that of the mesial temporal structures are not sufficient to justify the entire symptomatologic panel of schizophrenia, since it is always appropriate to consider the broader phenomenon of interactions between different cortical areas [1]. On the basis of measurements obtained with neuroimaging techniques, in fact, we can more correctly speak of dysfunctional connection, the core of which is constituted by the abnormalities highlighted by PET in the prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes [2]. As a consequence, the inability to control impulses and, in general, social behavior subsequently causes a mismatch between perception and linguistic action, to such an extent that the content of the message is often based on contradiction or even nullified by the presence of an oppressive superior entity. On the other hand, it has been documented that in 40-50% of cases schizophrenia is characterized by significant differences especially in the frontal lobes, hippocampus and temporal lobes [3]. The linguistic impairment and chaotic word flow, that in the case of the patient we are going to analyze are expressed mainly by self-referentiality and self-negation, seem to be related to the failure in slowing down nerve activity due to a reduced function of glutamate NMDA [4]. The language markers of the patient we have adopted as a case study actually become part of the set of psychotic symptoms generated by the subcortical dopaminergic variation. Otherwise, the continuous semantic violation and failure to respect the maxims of linguistic cooperation would not justify themselves in any way. The work of linguistic analysis we have carried out, however, aims to show that the alienation and the absence of communication references do not deprive the schizophrenic's language of clear linguistic sign and accessible semantics, although the code of this semantics is to be acquired through an internal coherence within the patient's own world.

The patient encountered for this contribution has spent approximately forty years in a psychiatric hospital. After the closure of specific mental hospital structures regulated by Law 180 of 1978, he became a member of a rehab community where, in addition to being treated with psychotropic drugs therapy, he is subjected to a psychotherapeutic re-education program. His diagnosis is Disorganized Schizophrenia (Hebephrenia), while his symptomatic manifestations are so advanced as to totally impair not only his cognitive functions, but also his relationship with the other patients in the community, who, although suffering from schizophrenia, find his linguistic oddities and behavioral extravagance 'amusing'. We met him on several occasions and listened to him during some group interviews that took place over the course of a year in Palermo, under the guidance of two psychotherapists. From the very first interview, we defined him as word-vomiting. He could be overbearingly distinguished from the other members of the community group for an unstoppable disorganized speech, a sort of hyper-individualized idiolect, a personalized language dominated by the themes of priesthood, military life, school and facts overlapping with man's will, crushing and annihilating his examination of reality. During group discussions, his white, frayed hair was motionless, his gaze absent, he huffed and muttered; often and suddenly, he would leave his seat to go and make coffee, a drink which he was disproportionately fond of and which, he had repeatedly been forbidden to drink, for obvious reasons. Similarly, he would make extremely insistent requests for food and complain about his guardians depriving him of pasta. What caught attention was undoubtedly the kind of “word-salad” the patient unloaded onto the psychotherapists, in the form of language that continually deviated from the conventional purposes of communication. All attempts made by any interlocutor to start a conversation were shredded and scattered. Anyone attempting to follow and understand the speech of the word-vomiting patient suffered a bombardment of linguistic stimuli: they were fascinated and astounded, but also frightened, being suspended in midair speech, harnessed in language games where order and meaning imposed themselves far beyond a code of belonging and sharing.

On the basis of our analysis, we feel we can assert that the theories according to which the language of the schizophrenic is characterized by a lack of transparency of the linguistic sign does not have any logical-argumentative foundation. The linguistic sign must be evaluated within a corpus of functions and concepts, unless one wishes to downplay the phenomenological component of the distress. The value of individual semantic segments may appear as self-referential and obscure or ambiguous because cognitive functions are impaired, but the meaning dimension can be reconstructed on the basis of organic interpretation. Although an extralinguistic referent is almost always missing in speech and words constantly refer to a sort of otherness, we can figure out the existence of a metalinguistic-structural process that the patient expresses almost passively, but to which we can still attribute values. In an attempt to show that there is a logical-argumentative criterion for analyzing the eloquence of the patient described, we have grouped his utterances into three sets. What is important to understand is that we have to interpret them in the way the phenomena appear to his consciousness, independently of the external world and independently of the way in which we narrate it. Certainly, we will not find the structural coherence that we expect from an ordinary speaker in his speech, but at the same time he will not lack a referential plane (otherness), an enunciative plane (contradiction), a logical plane (paradox) and a compositional plane (narration). In the same way, the schizophrenic patient gains a certain cohesion in the narration phase: recurrence, the use of connectives, chords et similia bear witness to this. If we correctly recognize the patient's mechanisms of coherence and cohesion, then we will be able to grasp his existential space, no longer a psychotic label, however necessary this may be. Before moving on to set analysis, it is right to say that the only irremediable deprivation is constituted by the maxims of co-operation so skillfully described by Grice in Logic and Conversation [5]. The schizophrenic will never be able to comply with quantity (never say more than is required, but neither less), quality (never say anything one believes to be false or without adequate evidence), relation (always say something relevant) and modality (always say something perspicuous, without obscurity or ambiguity, but with the necessary conciseness and order).

As we have already said, reading, analysis and interpretation can only be done in a systemic way. In fact, if we attempt to bring the sentence “Only I existed in the unknown of a real life (...)” into the figure, we are forced to annul its valence through the sentence “I do not exist as an examined person (...)”. It seems as if the pragmatics of language is lost in favor of an undefined ontology, in the moment in which the existential functions appear (“I have taken many exams”). In fact, the reality of “exams” is ideal, it is not tangible, while his “presence in the world” is “irreversible”. The dominant figure is definitely that of contradiction (“I existed” / “I do not exist”). Although the sentences are pronounced in a haphazard manner and without a precise sequence, the linguistic sign is clear and sharp: the patient's linguistic acts become incomprehensible only if we try to obtain something useful from them, only if we adopt the code of relevance and expectation [6].

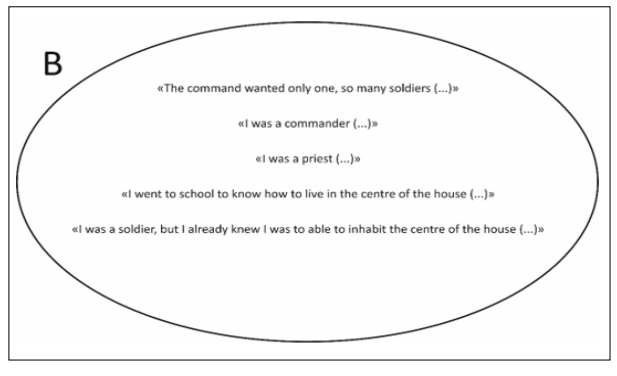

The function of the contraposition is also very evident in this set: “The command wanted only one” / “so many soldiers”, but also “I went to school to know how to live the center of the house” / “I knew I was able to inhabit the center of the house”. We move from the opposition between existing and non-existing to the opposition between “only one” and “so many”. That “one only” is a kind of anaphora of the “only I” of set A, that is to say a reprise of linguistic elements that provides cohesion to the speech, since we soon discover that the command that wanted something is represented by himself (“I was a commander”). Metonymy, in this case, becomes the key to understanding the whole set and is expressed in the identification between the narrator-identity and the object-entity. The necessity to learn how to inhabit the center of the house is the most chilling of the revelations of this disorganized eloquence because it unexpectedly makes us aware of the original sense of inadequacy of an individual who has never been able to act autonomously. Someone-something must guarantee learning for him, teach him how to intervene in experiential processes. The center of the house, the primal space of intimate existence, does not belong to him as an element of the natural learning process. It is as if a crack suddenly opened in the cemented walls of words. It is no coincidence that this sentence is followed by “I was a soldier, but I already knew I was able to inhabit the center of the house”, in which the nagging need for the daily exercise of a competence, is re-proposed, so even if that competence is supposed to belong to him by nature, all this happening always and uniquely under the immovable cover of an institution-entity. The sense of total bewilderment urges the individual with schizophrenia to find shelter and, at the same time, to alienate himself from a reality that can never prove to be protective and reassuring. Another consideration must be made with regard to this set: it is related to the use of verbal tenses and their concordances, that are respected despite the psychotic course. The cognitive impairment and the altered semantic memory do not prevent the patient from placing the action in the past and showing discursive continuity.

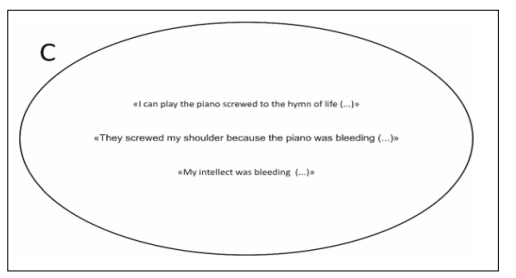

In the sentence “I can play the piano screwed to the hymn of life”, the past participle “screwed” can have a dual function: predicative of the subject or predicative of the object. We tend towards the first function because the patient states that “his shoulder has been screwed”. Thus, the second occurrence of the verb “screwed” allows us, once again, to follow a logical- argumentative path. Obviously, this path would be interrupted if we isolated the sentences apart from each other. The study of cohesion saves the value of speech. At this point, it is necessary to pay attention to the reconstruction of the sequence: (1) “I can play the piano (...)”, (2) “the piano was bleeding”, (3) “my intellect was bleeding”. For the second time, we can detect the phenomenon of metonymic-synecdotal identification between the narrator's identity (piano-player) and the object (piano) through a part of the identity (intellect). For the sake of fairness, we add that, in this set, the contradiction appears in the relationship between “hymn to life” and “bleeding”. It seems that the rhetorical-figurative circle leads us to consider the three nouns life, shoulder and intellect as linked, as if life were a hyperonym, that is to say a term of greater semantic extension than the other two, that accommodates the other two nouns of lesser extension, shoulder and intellect in its own category. On the surface, life and shoulder do not appear to be mutually related, at least from a lexical point of view, but since we know for certain that the word-vomiting patient is careful not to use terms that are rooted in the plane of reality and that the shoulder was screwed to him because the piano was bleeding, life is what man is tied-screwed to perform a piece of music; life is, in other words, the semantic dimension of the unknown in which all activity is, by ‘magic’, deactivated; it accommodates and conceals everything. At this point, shoulder and intellect, become hyponyms, that is to say terms of minor extension, and constitute a decisive synecdoche to indicate a shift in meaning towards what is necessary to be yearned to in order to realize the aimed purpose: preventing the loss of blood in order to perform the hymn to life. It is abundantly clear that here a rhetorical figure is not sufficient to justify the order and meaning of the construct.

If we recompose all the elements of linguistic analysis and acquire a unitary vision, we realize that the decrease in brain parenchyma and mesial temporal structures, the anomalies found in the frontal lobes, hippocampus and temporal lobes and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor are certainly compatible with “word-salad”, the absence of linguistic cooperation and the reproduction of sensory images, but the disorganization of language does not deprive the speech of an internal cohesion. Indeed, internal cohesion, although mostly conditioned by the delusional mechanism, is strongly expressed through the recurrence and metonymic or synecdotal identification between the narrative identity and the object. The object, in turn, represents the sense and meaning of the external agency that dominates the thought and language of the schizophrenic. From our point of view, that is an organic and phenomenological one, the schizophrenic's code is accessible and his linguistic sign is transparent [7-19].