Author(s): Wisdom Kofi Adzakor

The Ghanaian diaspora plays a crucial role in the development and cultural enrichment of Ghana. With strong ties to their homeland, diasporans contribute to Ghana’s economic growth through remittances, investments, and skills transfer. The Year of Return and Beyond the Return initiatives have successfully attracted diasporans back to Ghana, promoting tourism, trade, and investment opportunities. Through collaboration and mutual support, Ghana and its diaspora can work together to build a prosperous and inclusive future for all. This article explores the benefits, impact, and best practices of diaspora activities in Ghana, highlighting the importance of leveraging cultural heritage for tourism development, facilitating diaspora engagement for socio-economic growth, prioritizing community involvement and empowerment, and adopting holistic and inclusive development approaches. By capitalizing on the strengths of its diaspora community, Ghana can continue to thrive and prosper in the global landscape. The methodology used in this article involves a review of existing literature on diaspora studies, with a specific focus on the Ghanaian diaspora. Data from sources such as the Diaspora Affairs Bureau of Ghana and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs were analysed to provide insights into the demographics and impact of the Ghanaian diaspora. The article also draws on case studies, interviews, and reports to highlight the benefits, impact, and best practices of diaspora activities in Ghana’s development. The analysis is supported by empirical evidence, qualitative data, and policy recommendations to inform future strategies for leveraging diaspora engagement for socio-economic growth.

In his definition of diaspora, Safran lists six fundamental traits. He argues that in order for something to be classified as a diaspora, it must have spread from its place of origin to two or more foreign regions; those who are dispersed from their home have a collective memory of their home; they believe they will always be outcasts in their new state; they romanticize their alleged ancestral home; they believe that every member of that society should be dedicated to preserving and restoring the heritage of the homeland; and they have a strong sense of ethnic group understanding and a shared destiny [1].

Cohen expands on Safran’s definition of diasporas by adding four characteristics that, in his opinion, make up a diaspora: strong ties to the past or resistance to assimilation; a positive rather than negative definition; and a shared identity with co-ethnic members in other nations, such as colonial settlers, international students, refugees, and economic migrants [2].

According to diaspora formation can be explained by three key historical periods: the classical period, which includes the diasporas of Ancient Greeks, Jews, and Armenians; the present-day era, which includes the African diaspora and economic migrants; and the late current period, which includes a far broader spectrum of diasporic communities and a variety of reasons for voluntary or involuntary movement [3].

Ghana, located in West Africa, is a country rich in history, culture, and tradition. The country’s diverse population is a tapestry woven from various ethnic groups, each contributing to Ghana’s vibrant cultural landscape. The ancestry of Ghanaians can be traced back to ancient civilizations like the Akan, Ga-Dangme, Ewe, and Mole-Dagbon, among others. The Akan people, particularly the Ashanti and Fante, have had a significant influence on Ghanaian culture, with their rich traditions, art, and language shaping the country’s identity. Ghana’s history is marked by the transatlantic slave trade, where many Ghanaians were forcibly taken from their homeland to Europe and the Americas. This painful chapter in Ghana’s past has left a lasting impact on the country’s identity and cultural heritage, with many Ghanaians today having ancestral ties to diaspora communities around the world. Today, Ghana celebrates its heritage through festivals, music, dance, and art, showcasing the resilience and spirit of its people. Traditional ceremonies like the Homowo festival of the Ga-Dangme people and the Ashanti’s Adae festival are vibrant displays of Ghana’s cultural pride and unity. Ghanaians hold a deep respect for their ancestry, honouring their forebears through rituals, libations, and ceremonies that connect past generations to the present. An emphasis on extended family and community ties is a hallmark of Ghanaian society, with communal values and kinship playing a central role in daily life. In essence, Ghana’s ancestry is a tapestry of diverse ethnic groups, histories, and traditions that together form the rich cultural fabric of the nation. Ghanaians embrace their heritage with pride, demonstrating a deep connection to their roots while embracing modernity and progress in a rapidly changing world [4].

According to the Diaspora affairs bureau of Ghana (2019), Ghanaian migrants are found in over fifty-three nations worldwide, with the bulk of them speaking English. According to World Bank estimates, 1.7 million Ghanaians, or 7.6% of the country’s total population, live overseas. Based on data from censuses conducted around 2000, 957,883 Ghanaians, which constitute 4.6% of the country’s total population, were estimated to be living elsewhere. An additional three (3) million Ghanaians are thought to be living overseas.

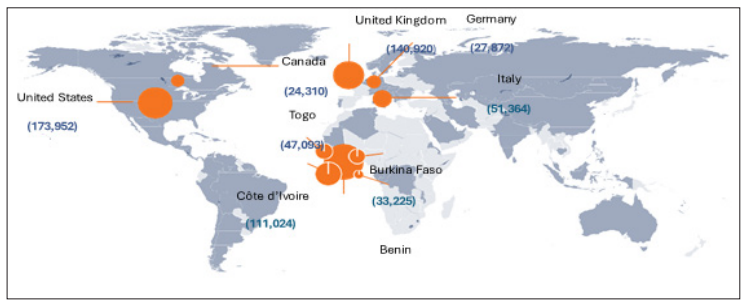

Though more Ghanaians are migrating abroad, the ECOWAS nations serve as the primary destinations for Ghanaian migrants inside the African continent. Nearby nations including Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire are home to over 55% of all Ghanaian emigrants. Other popular destinations for Ghanaians on the African continent are South Africa and Sierra Leone. Ghanaians who live abroad primarily go to the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, and increasingly, Italy and Spain. Ghanaians travel primarily to English-speaking nations because of their language ties.

Source: UN DESA, 2019.

Figure 1: Top Ten Countries with The Largest Ghanaian Immigrant Stocks, 20.

The figure above was taken from United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and duly acknowledged. In the figure, as of 2019, a whopping 173, 952 immigrants and known people of Ghanaian descent were recorded in the United States followed by 140,920 in the United Kingdom, 111,024 in Cote d’Ivoire, a neighbouring country to Ghana and Italy, Togo, Burkina Faso as well as Canada.

Ghana has developed some unconventional strategies to reach its target diasporan community. Ghana’s government and people, using policies, special invitations, the awarding of traditional titles, free land offers, and the promotion of Pan-Africanism, have managed to turn diasporans from tourists into willing ambassadors abroad, active cultural brokers, and subjects in the nation’s economic development. As previously mentioned, the African diaspora market in Ghana is made up of people who were originally from the continent but were later scattered by the transatlantic slave trade. Contemporary Ghanaian migrants reside in Europe, North America, and other parts of the world.

This article limits the Ghana diaspora market to Black Americans living in the United States and the Caribbean, as well as Ghanaian migrants in Europe and North America. The following section outlines some potential travel motivations for each segment mentioned in the literature. North America and the Caribbean diasporan (nacds) are likely to travel to Ghana for a variety of reasons:

Sixty-three (63) percent of Ghanaians who reside in the United States and visit their home country at least once a year or more, according to Orozco. Ghanaians living overseas could go back to see friends and family to reestablish ties with their communities and customs. In addition, some of these returnees build homes and businesses in preparation for their eventual permanent return [6]. Ghanaians often cite a sense of patriotic duty to return home in order to use their abilities in development initiatives (e.g., teaching at universities, improving government) and to make up for the educational privileges they were afforded, to be honoured by acquaintances, relatives, and close friends for their professional and personal accomplishments while living overseas (Ammassari, 2004); and to have the chance to look for and establish consistent sources of supply for their enterprises while residing overseas [7].

The Ghanaian government made several declarations and pledges that were either partially or completely delivered, frustrating diasporans in their attempts to draw them back. The President of Ghana from 2001 to 2009, John Kufuor’s Right of Abode laws only partially implemented his predecessor Rawlings’ offer of citizenship to NACDs. Only after seven years of residency are NACDs granted permanent residence. Due to a lack of funding, ROPAL, which was passed to enable Ghanaians living abroad to cast ballots during elections, was not used in the 2008 presidential election. The swift implementation of the dual-citizenship law has raised constitutional concerns in Ghana, particularly regarding its impact on members of Parliament who hold dual citizenship. As stated in Chapter 10, Article 194, Clause 2(a) of the Constitution, individuals cannot serve as Members of Parliament if they owe allegiance to a country other than Ghana. However, the Citizenship Act of 2000, under Act 59, Section 16(1), grants dual citizens the same rights as Ghanaian citizens. This contradiction has led to legal challenges, with courts being called upon to determine the eligibility of foreign-born Members of Parliament. The situation has created uncertainty and prompted disillusionment among Ghanaians living abroad, who was optimistic for the Homecoming Summit. Despite significant publicity and anticipation, the summit failed to meet initial expectations.

In January 2019, Ghana initiated the Year of Return (YoR) program to commemorate 400 years since the first enslaved Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. This year-long event invited the African diaspora to honour the collective resilience of victims of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, dispersed across North America, South America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia.” The program’s official website outlined its objective of increasing tourism to Ghana by positioning the country as a premier destination for the African diaspora, with a particular focus on attracting African Americans. Moreover, the initiative underscores Ghana’s dedication to the United Nations’ International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024). This decade-long effort aims to highlight the contributions of individuals of African descent globally while advocating for the promotion and protection of their human rights.

The YoR program has garnered widespread acclaim for its success, drawing in over one million tourists to partake in activities celebrating “the resilience of the African spirit” (Whitaker, 2019). It symbolizes a broader trend within Africa to bolster the tourism sector, stemming from the neoliberal reforms implemented in many African nations since the 1980s to spur economic growth. Beyond generating tourism revenue, the Ghanaian government has actively encouraged Africans in the diaspora and members of the Black community to return to Ghana and invest in the country. President Akufo-Addo reinforced this message with the launch of the YoR’s successor, “Beyond the Return: A Decade of African Renaissance” (BtR). This initiative aims to foster more positive engagement with Africans in the diaspora and individuals of African descent, particularly in trade, investment cooperation, and skills development. Ghana saw an unprecedented amount of visa applications and tourist arrivals, with the number of tourists rising by 45% (237,000) between January and September 2019. After the YoR, the Ghanaian government quickly initiated another activity called “Beyond the Return” to continue attracting diasporans to on a yearly basis visit their various ancestorial origins in Ghana. “Beyond the Return” is a 10-year project that follows the successful “Year of Return” campaign in 2019.

Ghana benefits significantly from its diasporans in various ways. One major advantage is the substantial flow of remittances sent to relatives back home. Officially recorded remittances increased from $263 million in 1995 to approximately $753 million in 2001, according to [6]. When informal channels are considered, this figure escalates to nearly US $3 billion (Mazzucato, van den Boom, & Nsowah-Nuamah, 2008). Presently, these remittances account for one-third of the country’s GDP surpassing bilateral aid in recent years [7,6].

Additionally, returning Ghanaians play a vital role in stimulating the local economy through their expenditures on goods and services. They contribute to housing development and business ventures, with reports indicating that a significant portion of new housing stock in 2005 was owned by Ghanaians living abroad [7]. Moreover, their impact extends beyond Ghana’s borders, as seen in examples like a cooperative in Italy importing Ghanaian pineapples [7]. Associations such as Sankofa and Sikaman mobilize foreign capital for Ghana’s economic advancement, initiating projects like the Sankofa Family Poultry Project (Orozco & Rouse, and facilitating trade agreements with businesses abroade. Sankofa and Sikaman is a Twi language that means “bring back the money to the homeland” [8].

Highly skilled diaspora Ghanaians contribute significantly to the country’s reconstruction efforts. Figures like Herman Chinery- Hesse and Ken Afori-Atta have established successful ventures, introducing innovative software solutions and financial services that benefit local businesses and investors (Brier). Moreover, individuals like Patrick Awuah leverage their international networks to enhance educational opportunities, as evidenced by the establishment of Ashesi University (Brier). Ghanaian associations abroad also play a crucial role in improving living conditions back home. Initiatives like fundraisers for safe drinking water and disaster relief efforts demonstrate their commitment to supporting their homeland. Likewise, visiting and relocated non-African diaspora citizens (NACDs) contribute to Ghana’s development by generating revenue, investing in businesses, and engaging in philanthropic activities such as constructing educational facilities and donating educational materials. These contributions, whether financial or cultural, enrich Ghana’s societal fabric and contribute to its overall progress and prosperity.

The Year of Return and Beyond the return initiatives have illuminated crucial lessons regarding the significance of leveraging cultural heritage for tourism development, harnessing diaspora engagement for socio-economic growth, prioritizing community involvement and empowerment, and adopting holistic and inclusive development approaches. These insights can be formulated into effective policy interventions in the following ways.

Firstly, Ghana’s rich history and cultural heritage have proven to be significant attractions for visitors during these initiatives, leading to a notable increase in tourist arrivals and revenue[9]. To translate this lesson into policy, policymakers should prioritize investments in tourism infrastructure, promotion, and marketing efforts. This entails highlighting Ghana’s unique cultural assets and historical sites through the development of heritage trails, cultural festivals, and visitor centres. Moreover, targeted marketing campaigns aimed at key international markets can further enhance the visibility and appeal of Ghana as a tourism destination.

Secondly, the involvement of the diaspora has been instrumental in supporting the success of these initiatives through investments, philanthropy, and knowledge exchange. To capitalize on this potential, policymakers can implement policies that facilitate diaspora engagement and collaboration across various sectors such as business, education, healthcare, and technology. This may involve establishing diaspora investment schemes, facilitating skill exchange programs, and creating networking platforms to connect diaspora members with local stakeholders.

Furthermore, the active participation of local communities has been pivotal in organizing events, providing services, and preserving cultural heritage sites [10]. To build on this lesson, policymakers should prioritize community-based development approaches that empower local communities to actively participate in decision-making processes and benefit from tourism revenues. This could include the implementation of community-based tourism initiatives, capacity-building programs, and revenue- sharing mechanisms to ensure equitable distribution of benefits.

Lastly, the Year of Return and Beyond initiatives have underscored the importance of adopting holistic and inclusive development approaches that address social, economic, and environmental dimensions [11]. Policymakers should prioritize the adoption of integrated development frameworks that align with sustainable development goals, promote cultural diversity, and foster social inclusion. This may involve formulating national development plans, policies, and strategies that mainstream cultural heritage preservation, environmental sustainability, and social equity across all sectors of governance and development.

In conclusion, the Ghanaian diaspora plays a significant role in the country’s development and cultural enrichment. With a rich and diverse heritage, Ghanaians in the diaspora continue to maintain strong ties to their homeland while contributing to its economic growth through remittances, investments, and skills transfer. The Year of Return and Beyond the Return initiatives have successfully attracted diasporans back to Ghana, promoting tourism, trade, and investment opportunities. As Ghana continues to engage with its diaspora and embrace its collective identity, the country stands to benefit from the valuable contributions of its citizens spread across the globe. Through collaboration and mutual support, Ghana and its diaspora can work together to build a prosperous and inclusive future for all [12-15].