Author(s): Darwin S Torres-Erazo1 , Nelda J Nuñez-Caamal1 , Jorge A Valdivieso-Jimenez2 , Wendy K Alvarez-Manzanero1 and Maria A Salcedo-Parra1

The COVID-19 has affected million people around the world with Mexico being one of the most affected countries. This pandemic has impacted the continuum of care for people living with HIV so it was decided to know the frequency and usefulness of performing rapid HIV tests during COVID-19 pandemic.

During December 2019, a previously unknown betacoronavirus was discovered in samples from patients with pneumonia in China [1]. This new virus is currently named Severe Acute Respiratory Síndrome 2 (SARS-CoV2) and its clinical spectrum: Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19). This new coronavirus has affected more than 43.0 million people around the world and is responsible for more than one millon deaths with the number of confirmed cases increasing every day, with Mexico being one of the most affected countries [2].

Some risk factors have been described for infection with SARSCoV2, including HIV infection , but information about the clinical course of this co-infection is yet limited even though there are more than 37 million people living with HIV around the world during this pandemic [3,4]. Mexico has a low global prevalence (0.3%) according to UNAIDS, with more than 230,000 people living with HIV in 2018 (4) and Yucatán (state located on southeast of Mexico) has a lower prevalence rate (0.2%), but is the third place between all Mexican states in new cases diagnosed with a rate of 13.8 per-100 000 habitants [5].

Early diagnosis of HIV infection in any setting, decreases mortality in patients who debute with the disease and decreases health-care costs by reducing missing opportunities of diagnosis and appropiate management or treatment for other diseases and co-morbidities In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening as part of routine medical care in the United States for those aged 13-64 years and the benefit of this routine strategy has been reflected in different places regardless of the clinical setting or the place where it is performed, particularly in settings with high prevalence of infection and in emergency or trauma services [6-9]. This evidence has also been considered by the guide for the detection of HIV in Mexico, highlighting that emergency services are the best place for public health interventions and to cover opportunities in the diagnosis and early linkage of patients to clinical care [10]. The purpose of this study was to know the frequency and usefulness of performing rapid HIV tests to diagnose new cases, in people who were admitted to the respiratory emergencies unit in a tertiary Mexican hospital during COVID-19 pandemic.

We conducted a prospective study from March 9th to October 27th, 2020 to know the frequency of new HIV infections among persons admitted in a respiratory emergencies unit (REU) created at the High Specialty Regional Hospital of Yucatan Peninsula (HSRHY), a tertiary care hospital located in the southeast of Mexico and reconverted for the attention of patients with suspected or confirmed infection by SARS-CoV2 during COVID-19 pandemic.

The subjects included in this study were adults over 18 years admitted to the respiratory emergencies unit where they were evaluated by an internal medicine physician looking for clinical or epidemiological data suggesting HIV infection. Blood specimens from a finger prick sample were obtained by a trained nurse or research physician who performed the Advanced Quality™ HIV-1/ HIV-2 antibody test, manufactured by InTec Products, INC, and donated by the state program for prevention and control of HIV/ AIDS in Yucatan.

If the rapid test was positive, a laboratory phlebotomist took a second venous sample to be used for confirmatory testing, done using the standard HIV antibody (ELISA). If ELISA test resulted in positive, a CD4 cells count, western blot and viral load for HIV, were done. If ELISA resulted in negative, the rapid test was considered false-positive and no more tests were performed. No further HIV testing was performed on patients with a negative rapid test for HIV.

Patients who tested positive for HIV were evaluated by the infectious disease specialist and referred to the HIV Outpatient Treatment Center immediately upon discharge from the hospital. All patients gave their written consent to do the rapid test and take venous samples for HIV diagnosis if necessary. Patients who did not give their consent and those who, upon admission to the REU, reported living with HIV, did not undergo the rapid test and were excluded from the analysis and description of this study.

The SARS-CoV2 infection diagnosis was made using nasopharyngeal swab samples that were processed on state public health laboratory by amplification of betacoronavirus E gene and RdRp gene by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The results and findings were calculated and shown by descriptive statistics on the accompanying table and graphic.

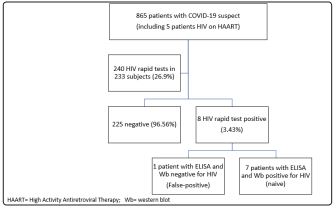

From March 9th to October 27th, 2020, eight hundred sixty five consecutive patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV2 infection were admitted to the REU of the HSRHYP (point-ofcare). During this period, a total of 12 patients with HIV infection were admitted, of which 5 knew their diagnosis and were linked to clinical care or antiretroviral treatment and 7 were new cases. 240 rapid HIV tests were performed on 233 subjects (26.9% of all admitted patients), of which 225 (96.5%) were negative and 8 were positive, equivalent to an incidence / seroprevalence of 3.43% (8/233) for the point-of-care. Seven subjects had reactive ELISA and Western blot tests and 7 tests were discarded due to poor technique in performing the test or for having used more than one test in the same patient. Figure 1

All patients gave their consent for the test and none refused to carry out the rapid test or the complementary studies.

Figure: Patient Flow for HIV screening in study sample recruited between March to October 2020 at REU from High Specialty Regional Hospital of Yucatan Peninsula

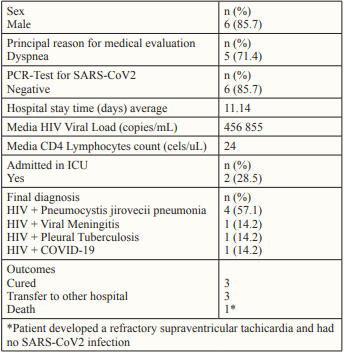

The mean age of the 7 subjects with a positive HIV rapid test was 38.5 years (SD = 13.8). The highest proportion of patients were men (87.5%) and 4 of them (57.1%) had male-sex-male relationships as a risk factor for HIV. The mean CD4 count and HIV viral load were 24 cells/uL and 456 855 copies/mL, respectively. The reasons for the patients seeking medical attention were primarily dyspnea and fever, but they also experienced other symptoms such as cough, headache, odynophagia, diarrhea, nausea, arthralgia, myalgia, and diaphoresis. Only one patient (14.2%) had co-infection with SARS-CoV2 confirmed by RT-PCR. The results of the laboratory tests and outcomes in the subjects with a positive HIV test are shown in Table 2.

Table: Clinical, laboratory and outcomes from new HIV patients identify during rapid test screening at point-of-care of High Specialty Regional Hospital of Yucatan

All the subjects who were reactive for HIV were unaware of their previous immune and virological status, except the female patient, who did not mention her diagnosis upon admission for fear of being rejected by medical care. The subject who was positive in the rapid test but not reactive in the ELISA and western blot test for HIV, had risk factors for COVID-19 (obesity and hypertension) and his PCR test for SARS-CoV2 was positive. His evolution was torpid and he died 12 days after his admission due to complications related to COVID-19.

Without any doubt, the emergence of the SARS-CoV2 pandemic has become a growing challenge for health services around the world [11,12]. In the particular case of HIV, the barriers and challenges ranged from a dramatic reduction in access to routine diagnostic tests to delays in the link to medical care or the postponement of initiating antiretroviral treatment and guaranteeing its provision. The impact of these obstacles has resulted in limitations in achieving UNAIDS ‘goals of reaching the three 90’s, which is why quick and effective strategies are required to maintain the continuum of care for people living with HIV [13].

HIV screening is one of the control measures that has been affected in our environment during the pandemic by various circumstances that include fear, stigma or discrimination, as has happened in other parts of the world [14]. In contrast, the implementation of a screening aimed at people with clinical or epidemiological data suggestive of HIV infection at our point-of-care allowed the identification of a significant number of people (3.0%) who were unaware of their disease, but had symptoms and signs that were misinterpreted as COVID-19. This finding suggests that screening for HIV diagnosis in scenarios such as the SARS-CoV2 pandemic could help to not miss the opportunities to diagnose and link to care for subjects living with HIV, which, on the other hand, in the case of our unit they continue to present late or with advanced disease (<50 cells / uL) and with high viral loads (> 100,000 cop / mL), as has been the case for several years in Mexico [15,16].

The seroprevalence found in our Point-of-test is high compared to that reported by the state HIV control program , which allows us to propose that a greater application of tests (screening extended to all patients) perhaps could have identified more naive patients with HIV infection and unaware of their status, as has happened in other care centers where routine and universal screening is well established, which would reduce missed opportunities for the diagnosis of HIV / AIDS during the COVID-19 pandemic [5,17- 19]. The findings of this work also showed that symptoms related to HIV infection or its opportunistic complications could have been misinterpreted as caused by SARS-CoV2, which highlights once again the need for physicians to be trained and educated in HIV medicine. to improve outcomes, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [20,21].

The present work has limitations due to the small number of patients screened which reduced the possibility of doing a more extensive statistical analysis. However, it was highlighted that during the pandemic it is possible to continue with the diagnosis, care and to management of people living with HIV and to our knowledge it is the first Mexican report of HIV diagnostic screening during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Screening for the diagnosis of new cases of HIV infection is feasible, useful and safe to perform during the COVID-19 pandemic. The application of a routine and extended screening in respiratory emergency units or triage points could help to better understand the local prevalence of HIV infection and decrease mortality attributed to SARS-CoV2 through appropriate management of opportunistic infections due to HIV. It should not be forgotten that there is a current need for HIV education for health personnel working in emergency services and that this need has currently been exacerbated because HIV or its complications can mimic other infections including those produced by SARSCoV2.

To the medical and nursing staff of REU-HSRHY who collaborated with the clinical identification of patients with probable HIV infection, Dr. Dulce María Cruz Lavadores for facilitating the donation of rapid HIV tests and Dr. Richard Douce for his support in reviewing the manuscript.