Author(s): Jimena Silva Segovia*, Estefany Castillo Ravanal, Daniela Vargas Castillo and María Menanteux Suazo

In this research, we explore how the experience of gynecological-obstetric violence manifests in the lives of Chilean women. Additionally, we identify the emotional strategies emerging from these experiences. In this qualitative study from a gender perspective, we conduct 21 in-depth interviews with Binary and No Binary (NB) people in the communes of Antofagasta and Calama who have been treated at public or private health facilities. Among the most relevant findings are emotional experiences involving guilt, fear, and shame. We conclude that one of the relevant damages concerns the body and sexuality that are harmed due to the dehumanizing nature of the experiences during obstetric or gynecological care. Thus, an aggravating factor is the hetero cis norm that is imposed on diverse corporality’s. Three models of experience analysis useful for interdisciplinary teams are presented as references for the impact of health services on users.

In this article, we explore from a qualitative perspective the coping and protection strategies used by binary and nonbinary (NB) women facing episodes of gynecological and/or obstetric violence. We analyze the emerging subjectivities from these experiences and identify the emerging emotions in terms of the relationship of gynecological and obstetric care for women of sexual diversity [1,2].

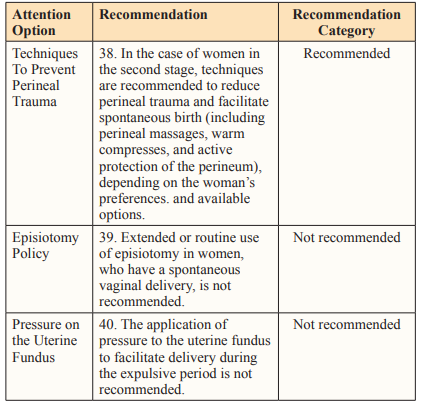

We focus on GOV in the practices of health professionals in gynecological and/or obstetric care, who, within their work, exercise practices typified by the participating women as violence in institutions of health. This situation, in many countries, is naturalized as part of the protocols in a “care model”, rendering anomalous situations invisible and preventing the assignment of responsibility to health agents involved. Specifically, we refer to the practices classified as routine that are promoted as part of gynecological or obstetric practices such as the use of generalized episiotomies, implementation of intravenous opioid chemicals to accelerate labor, application of enemas, and public shaving, among other gynecological and obstetric protocols, in contrast to the recommendations of the Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) (Table 1).

Source: Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) [2].

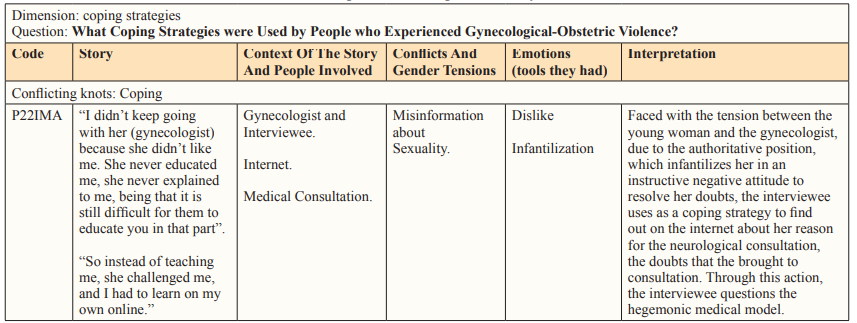

Note. Protection used in the face of GOV-VGO (first column), guided according to emotional experience (second column), giving way to emergent agencies to cope with violence (third column).

We define GOV using Law No. 38,668 in Venezuela (2007), which was the first country in Latin America and the Caribbean to develop an “Organic Law on the Right of Women to a Life Free of Violence” in their gynecological experiences:

The appropriation of the body and reproductive processes of women by health personnel, expressed in a dehumanizing treatment, is an abuse of the medicalization and pathologization of natural processes, entailing a loss of autonomy and decreased ability to freely make decisions about their bodies and sexuality, negatively impacting the quality of the life of women (p. 129).

From a gender perspective, in the structures of unequal sociocultural relationships are the bases for different types of violence. In the case of GOV, this is hidden by the silence of those who have suffered from them in private because in many cases, these experiences have left them exposed and vulnerable in situations that involve their privacy. As practices of violence, they are gestated in doctor-consultant links through mechanized actions that have been questioned by different organizations over the last 10 years: unnecessary episiotomies; oxytocin serums to accelerate labor; and indiscriminate uses of instruments such as specula, scissors to break membranes, and intravaginal ultrasounds, among other procedures. Observations of these practices have produced extensive research on when their application is recommended and when it is not [3-5]. However, these continue to be perpetuated without any reparation; thus, GOV has become an expression of the type of authoritarian gender relation that has informed multiple attacks against women, identified internationally [6,7,8].

In societies with neoliberal economic models of health, these services tend to commodify health care, hardening the gaps between public and private health, where the people who have the least educational and economic resources tend to be those who experience the greatest GOV. Economic gaps affect the exercise of the sexual and reproductive rights of women in health care, where the power of the word of professionals is imposed on users. In scenarios with these characteristics, testimonies typically favor an infantilized relationship between women classified as “patients” and their treating doctors. In addition, in many cases, doctor’s offices automatically assume the heterosexuality of all patients or those who have already initiated sexual activity.

Regarding the population of people of dissent, a concern in this study is that people assigned the female gender at birth are the least benefited in a model of medicine with an authoritarian physician-consultant hierarchy, since most of the widespread gynecological-obstetric procedures have not been adapted to the needs of dissident women who attend consultations. Many health professionals adhere to the general regulations in health institutions; those who specialize or sensitize in this model of gynecological care are rather exceptional [9].

GOV has a severe impact on the health and life of the people who experience it, generating a series of clinical effects on and short- and long-term physical consequences for their lives [10,11]. At least once, they have experienced some type of degrading, humiliating or aggressive treatment or practice. In response to these experiences, many people stop attending to their gynecological health, and this is more frequent among people whose sexual orientation and/or gender identity does not adhere to the heteronormative model [12]. Gender-based violence can transform their subjective experience of themselves, their bodies, and their sexuality and thus deeply damage their relationships with their environment and bodily self-care [13,14].

In this regard, recent research from Chile [15,16]. Has offered data on which practices are perceived as violence by users to contribute to the development of a humanizing treatment model in the current medical system with appropriate protocols and a professional health team. One of these is the “First National Survey on Gynecological and Obstetric Violence in Chile (2019-2020)”

By the Collective Against Gynecological and Obstetric Violence, which highlights how 67% of the people surveyed had experienced gynecological violence and 80% obstetric violence, driving a subsequent deterioration of their bodily self-image (34.76%), their perception of their body (42.75%), their self-esteem (45.74%) and their sexuality (39.83%). As a consequence of these episodes, these people were referred to mental health care (17.83%), alternative therapies and/or support networks (27.43%).

This survey has also exposed a high rate of complaints that were not executed concerning cases of sexual violence during care (93.94%); in contrast, 3.11% tried to complain but were not received, and only 2.95% managed to complain effectively. Other forms of GOV are dehumanized care or treatment, the use of unnecessary or intentionally painful procedures, the abuse of medication, the transformation of natural processes into pathological ones, and the denial of information or treatment.

We have also observed the routine performance of practices or interventions advised against by the WHO [8] (see Table 1) for more than two decades; these continue to be applied [16]. One of these is the high number of cesarean sections performed in health centers, a practice that should only be performed in an emergency. According to Puchi et al. South America is the continent with the highest rate of cesarean sections (42.9%), followed by North America (32.3%), Oceania (31.1%), Europe (25%) and Asia (19.2%). In the case of Chile, during 2015, the rate of cesarean sections was 47%, ranking among the highest rates in the world with Turkey and Mexico, which range between 45% and 50% [17,18].

Having elaborated the context of GOV, we contribute a set of subjective experiences to these statistical findings by addressing the following questions and exploring them with a set of consultants

To deepen the perspectives of gender and human rights, we use the intersectional feminism literature as a theoretical-methodological reference, as it facilitates understanding how women develop their coping strategies when experiencing violence. Additionally, emotions triggered by violence are articulated through sexual identity, socioeconomic status or accessibility to support networks, which are fundamental in the emergence of a type of strategy [19-22].

Thus, we also consider intersectionality, which allows us to analyze how, at a symbolic level, bodies are incarnated in a socialfabric saturated with classificatory constructions imposed by the gender and sociocultural order. Hence, what is understood as body and identity control is exercised by the dominant institutions in a culture, such as medicine, which from different angles control the sexual and affective work of the female body-in this case, through the doctor-consultant relationship. These relationships, being hierarchical, produce a type of dominant discourse that is reproduced in health service and goes beyond sexual and reproductive education, as the sciences in one way or another reiterate certain installed biases [23-28].

The hierarchies built in the doctor-consultant relationship produce an emotional experience in women. These emotions are socially constructed processes arising from links and experiences with educational institutions, such as family, school, or church, implying, in all these discourses, moreover, how medical knowledge in Latin American societies is usually unquestionable [6,27]. In short, an emotional experience is not a series of events that occur linearly, but a subjective experience structured in the social fabric and mainstreamed by the dominant ideologies in its context.

Along this line, the guiding role of emotions in their social character is apropos when evaluating the coping and protection strategies that are used to avoid a situation of violence. According to Lazarus and Folkman, from a cognitivist perspective, coping strategies are “those constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts that are developed to handle the specific external and/or internal demands that are evaluated as a surplus or overflow of the resources of the individual”. Thus, using other theoretical models, some authors analyze where experiences with violence are located, pointing out that although a strategy used in the past was somewhat ineffective in the face of violence, it cannot be judged by the lack of a better one in the face of a new attack; the priority is survival, not necessarily efficiency or well-being. Therefore, there are no better or worse coping strategies-due to the complexity of the issue, success or failure must be analyzed with various factors, e.g., the context or characteristics of a stressgenerating situation [29-31].

Furthermore, one of the intense stressors faced by a woman in labor in Chile is the cost of medical care due to the privatized health system in its prevailing neoliberal model. In Chile, there are deep socioeconomic gaps between different segments in the population, causing a significant part of it to lack the economic resources for entering private clinics (with better treatment) or community clinics that offer comprehensive care with respectful and dignified planning, gestation, delivery and/or postpartum processes. According to the National Institute of Statistics, to be treated at a private clinic, one must have an income between 1 million and 5 million pesos; however, 50% of employed persons in Chile register a maximum income of $420,000 per month [32].

In response to this scenario, different investigations have proposed various multidisciplinary health care models to escape the patriarchal and capitalist logics of the current medical model, with permanent teams of social workers, psychologists and midwives who are knowledgeable about mental health; these models are based on responsible contributions from ethics and politics to the comprehensive, respectful, and humanized care of those who request services [20,33]. Among the social workers and psychologists in the field of health in our focal context, we have observed specific knowledge gaps concerning obstetric violence and the specific strategies and protocols that can reduce or eliminate GOV. During Chilean academic training, case studies, investigations or interventions involving women who have experienced these types of violence are not analyzed.

Our methodological model is qualitative to allow the deepening of our analysis of the intersubjective significance of the experiences, perceptions, feelings and emotions concerning the strategies of coping and protection used for GOV. For this, we have been inspired by a feminist epistemology because it explores the relations of power, inequality and the precariousness of women’s rights, allowing us to maintain our ethical responsibility during our investigation. That is, this position recognizes that any experience occurs within a specific social context that cannot be ignored because this deterritorializes the experiencer and ignore the political and ethical meaning of research. Thus, we are responsible for making critical gender observations while safeguarding the correspondence between researcher and researched subject [34- 40].

The participants in this study were female (assigned as “woman” at birth) within an age range of 21 to 56 years and of Chilean nationality; they had all received, at least once, gynecological, or obstetric care in the Antofagasta region, interviewed in the period of 31 of May 2021 an 15 of December 2022. They perceived these experiences as uncomfortable, aggressive, violent, or humiliating, i.e., as some type of violence. Our sample comprised 17 cisgender women, 1 NB woman, 1 NB male trans person, and 2 NB people; 10 were heterosexual, 6 bisexual, 3 pansexual and 2 people selfassigned as undefined in their sexual orientation. All of them are registered in different private and state health insurance systems.

The participants were identified through the snowballing method, which is often used to contact populations or groups that are difficult to access, also known as hard-to-reach populations [41]. Complementarily, we used Instagram to distribute an image summoning people interested in offering their experience voluntarily that was also positioned in strategic spaces in the municipality of Antofagasta.

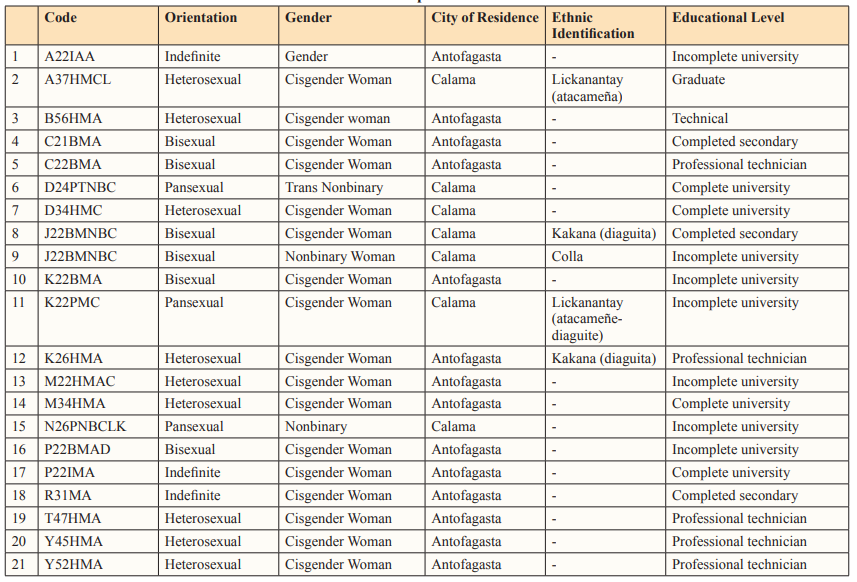

The identification code of the participants lists their initial, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, city of residence and membership in an indigenous people/nation, respectively (Table 2).

Own Elaboration.

Note: The identification code of each participant has in order the initial of the name, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, city of residence, and belonging to an indigenous people/nation.

In the article we refer to women, as cisgender people; and to people of sexual dissidence linked to gender identities, such as: trans, non-binary, gender; and sexual orientation, such as: bisexual, pansexual, unidentified.

Due to the characteristics of the study, the participating population was considered difficult to access; a safeguard was used to prevent them from being contacted or identified to avoid any the risks that reporting an experience of gender violence entails [42]. Each participant read and signed a consent form approved by the CONICYT ethics committee. In Chile, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health has established movement restrictions and confinement measures to prevent the spread of the virus. For this reason, some interviews could be carried out in person, while others had to be carried out remotely, through the Zoom platform. The content of these interviews was recorded in audio and video, which was made explicit in the informed consent signed by the participants, residing in different areas of the country.

Finally, individual in-depth interviews were used to obtain participants’ opinions, perspectives, and experiences in addition to any other matters the deemed relevant [43].

The analysis of the information was carried out in accordance with the proposals of Van Dijk for the analysis of critical discourse (ADC), considering it as a valuable tool to investigate the construction and reproduction of relations of power and inequality through language. As a first step, the research team identified the object of study and its sociopolitical relevance, which implied selecting the documentary corpus made up of the narratives of each of the interviewees. Subsequently, an analysis of discursive structures was carried out, which was carried out based on a set of dimensions, grouped into four axes: history of consultations, experiences with GOV, networks and support tools, and retrospective suggestions for the medical system. Cognitive analysis involved the team examining beliefs, knowledge, opinions, and ideologies present in the discourse, as well as the way in which these influence the interpretation and production of the same. Thus, matrices were elaborated that were synthesized based on a experiences of GOV in the region, b emotional experiences in gynecological care, and c coping strategies of GOV. Finally, in the contextual analysis an emerging comprehensive model was developed for each axis (Table 3), which allowed us to elaborate the relationships between conflicts and violent experiences, facilitating our response capacity to research questions and organization of the material [44-47].

Throughout the process, the research team safeguarded the exercise of reflexivity, considering in a particular way their own positions, beliefs, interests, and power relations in relation to the object of study. This reflexivity, exercised transversally and in open spaces for discussion, allowed greater transparency and rigor in the analysis, as well as the identification of possible biases and limitations [48].

Own Elaboration.

Our findings were organized according to our guiding question: How do women and NB people in the Antofagasta region identify their experiences with GOV? With our findings, the first analytical model that allows the identification of emerging conflicts, emotional experiences and GOV was developed.

The model places the question as the central axis that analyzes the findings, which include a critical look at the power relations between consultants and doctors, in a sociocultural context of hierarchies that are reflected in conflicts, provoking emotions in the face of the violence experienced. Own Elaboration.

The figure articulates the emerging emotions in the face of gynecological and obstetric violence in relation to three axes: sexuality, doctor-consultant relationship, and corporality. Own Elaboration.

In this dimension, the emerging set GOV narratives in the Antofagasta region was analyzed. We focused on the subjectivity of the emotional experience of each person beyond its actual situation while considering the framework in which these tensions occur: a neoliberal and patriarchal system.

In this context, health care in the region is defined by the traditional medical model; one that is subject to the changes in thought in each era, to the territory, to new technologies, and, in this case, is dependent on financing from mining companies or differences between the province and regional capital. As a result, there are clear centralist differences in relation to the population’s access to health professionals-the majority of medical care is at the service of mining or in the private sector.The first column on the intersectional map expresses the relationships between the relevant conflicts; the third column concerns instances of obstetricgynecological violence. Both sections are cross sectioned by emotional experience according to three aspects (consultation or attention, body and sexuality).

GOV can be exercised by any health professional involved in gynecological and/or obstetric care from the moment they enter a campus [1,20]. Regarding the emotional experiences of GOV, the predominance of fear, guilt and shame was observed in all the stories. Other conflicting emotions were anguish, loneliness, anger, anxiety, disgust and, with this, pain in its affective dimension, allowing us to understand the emotions that revolve around GOV [31]. These conflicts and their associated GOV are elaborated as follows:

The paramedic sees me and says, “How are you lying down here? Surely, you are used to having everything done in the house. Look how you are! All stinky, and you have not even cleaned yourself.” Lazy-he did not want to clean me. He said, “I am not going to clean you because I am not going to promote laziness for anyone. (T., 45 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta) After the consultation, I go to a room to put on clothes, and there, the gynecologist touched my butt. My whole body froze; I sweated cold all at that precise moment. I saw the closed door, and I said, “I already went.” He would not stop talking about the family at any time and, suddenly, he pats me again. (A., 22 years old, gender, Antofagasta) Two forms of the hierarchical and authoritarian relationship are expressed in these reports, both among health personnel and the doctor-patient, configured within different positions of knowledge-power in which professionals impose an arbitrary right on a subject of care. Violence, as a construct, is reproduced through the adherence of the dominated to the dominant and to the domination itself [49]. In the case of GOV, the aggravating factor is that it occurs in services associated with the preservation of human life, such as health care. These exposed power relations subject the female body to the commands of obedience inscribed in the culture, directives personified in the staff invested with a dominant knowledge and a practice in the field of its domain. In this way, the role ofthe doctor and the knowledge-power of the biomedical woman prevail in the abovementioned cases mentioned as well as that of the nursing assistant who assumes the power of patriarchy that allows her to control the welfare in a hospital ward [50]. To analyze these relationships, an intersectional perspective is important for understanding that gender is connected with other axes of power inscribed in corporeality, such as socioeconomic level, age, race, context, region or commune, gender identity and sexual orientation [20]. In these examples, the doctor exercises a type of power over the body of a young woman that paralyzes her, rendering her unable to react to her harassment, and the nurse uses abusive language toward a woman recovering from childbirth. Both attitudes reveal emerging violence, which, in turn, works in favor of hierarchical relationships and bio power mechanisms.

With the gynecologist, I felt humiliated. He told me, “It doesn’t matter that you have PCOS; you have a lot of pimples on your face, and you have a lot of hair. I’m going to give you pills”. “What is wrong with my hair? If is normal” [she responds to the health professional]. In addition, he says to me, “Yes? Your pimples? Those you have on your face! (C., 22-year-old, bisexual woman, Antofagasta).

The matron became very hostile and heavy; it went directly at my physique: that everything I had was because of my weight, that the infections I had were because I was a whale, an obese woman. (J., 22-year-old, bisexual NB woman, Calama).

In these narratives, GOV is elided by a medical discourse that promotes the urgency of health care as the only measure for care, rationalizing the importance given to medical opinions in modernized territories [24]. As these experiences show, the professionals, located in a hierarchical relationship with the patients, construct a homogenized discourse about their bodies that does not respond to the “desirable sexual female body”, classified as “pathological” or “correctable” [24]. Specifically, hegemonic gender stereotypes are imposed, promoted by the conception of patriarchy concerning feminine beauty and consumerist capitalism through a medical discourse on the aesthetics of the body, skin and “healthy” body weight, i.e., bodies according to an imposed classification. This form of GOV is inscribed in the subjective experience of the self-image of the patients and their body [13].

They left me in the middle of the hall. They all saw me. I don’t know how many hours I was there. It was very cold, and nobody helps you at night. They don’t take care of you, they don’t help you, they don’t give you anything for pain, and with babies, it’s exactly the same”. (Y, 52 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta).

The gynecologist told me, “Since you are a newcomer, you put a lot of color on it, and you are very dramatic. Vomiting is normal”. (Y., 45 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta). In the exercise of GOV, obedience and endurance are expected both bodily and emotionally. This is part of the global cultural mandates that dominate the discipline; however, in these narratives, the women and their bodies, socialized as feminine, must accommodate their experience to failures in maternal and childcare. They resist by adapting to a behavior model that is the least disruptive possible within the health care space, as long as the expression of the female body is understood or represented by its reproductive function [24]. This dominant paradigm deprives the users of a medical accompaniment that responds to their needs and is consistent with the meaning of the situation of childbirth, as well as the pain and emotional exhaustion involved. On the other hand, the use of the knowledge-power device in the care processes is visible, exposing the disconfirmation of a patient’s experience by ignoring the relevant differences that each person may have in relation to the gynecological-obstetric situation. As a result of this dynamic, these women are reduced to the passive-compliant subjects of the protocols applied in this service [51].

[The hospital gynecologist judged:] “Why did you not take care of yourself before? Why did you not use contraception if you do not want to have children? Why are you going to do this? She assumed that I had had an abortion because I went to Aprofa [Chilean Family Protection Association], and I had told him I came from there (...) There was a lack of privacy and professionalism, the midwife was there giving her opinion and the gynecologist pointing her finger at me”. (K., 26 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta).

As part of this conflict, a criterion in the narrative is judgement, from ideological perspectives, of decisions related to the sexual and reproductive health of the users, violating the rights of the patient, who is expropriated of the knowledge-power regarding her own body through moralized, prejudicial and lectured punishment concerning the choice of when to become a mother [49]. In this regard, in the narrative of another participant, the generational mandates interpreted by reproductive medicine on the moment in which women should or should not face reproduction are evident: A midwife asks me, “Who sends you to have children so old?” I was 34, and it was my first baby. There were other younger girls; they said, “What do you think of having children so young?” And, it was supposed to me, because she was older. (B. 56 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta).

Thus, the imposition of contraceptive methods in any form establishes certain ideals higher than those of the patients. In many of the narratives based on the GOV, there are key aspects of institutional violence driven by the mechanized and technocratic nature that has been installed in the health centers attended by the participating women and, specifically, in care during abortion, childbirth or other associated actions. In this case, as a woman recovering from a loss comments: When they admitted me to the clinic, at no time did they tell me that I had experienced a loss. I remember that the gynecologist arrived. I don’t remember that he greeted me, but he said, “Wow, I was super good on the beach.” Like, I had cut off his walk. Less than a week after the loss, I go to the consultation with him, and again with that attitude that he was not looking at me. He says to me, “And how is the pregnancy going?” It was so mechanized; he didn’t even write it on the card that he would ask me that. And there, I felt hurt, I felt bad. (Y., 45 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta).

These forms of relationships, adopted under homogenizing protocols, are present in different narratives. They seem to respond to the demands of a style of practicing medicine and health care from capitalist perspectives that have turned physiological processes- reproduction and medical consultation-into profitable business [20]. As a result of this dynamic, professionals focus on fulfilling their technical work, focusing only on physical discomfort- an insufficient task for establishing the comprehensive medical provider-patient relationship demanded by gynecology.

I went to a gynecologist at 17, and she treated me lousy, like afool. I knew the care and protection. I told her that my first time, I did protect myself, but she challenged me. It was not enough, and why hadn’t I gotten the Implanon, so that I could not get pregnant...since everywhere, they tell you that a condom is more secure, I was shocked. Why do you tell me that it is wrong if they teach you the condom everywhere? It made me feel like I didn’t know anything. She only dedicated herself to challenging me and selling me the Implanon. She would sell it and use it herself; she told me that I should use it because it was the best. (P., 22 years old, female, undefined sexual orientation, Antofagasta).

Thus, such GOV queries are permeated by bio power and the hierarchical relationship between the two parties: The consultants are treated as uninformed people who need to be taught through punishment and scolding, which infantilizes the patients and implies that without handling the information presented the medical team, sexual practices should not be performed at all [26,49].

I was very afraid that she would observe me, that she would put something there (genital area). She just said, “Sit there.” I looked at the matron with a terrified face, and she asked me, “What’s wrong?!” There were many practitioners watching; it was very uncomfortable, because even though it is only your stomach, your pants are slightly lower. (D., 24 years old, trans NB pansexual, Calama).

This type of problem occurs due to a lack of training on sexual dissidence among GO personnel. In this framework, gender identities are assumed to be due to having female biological sex, but the way in which this corporality is expressed is not questioned, as it does not fit with the feminine standards of body, aesthetics and gender. This vision is complemented by a point already highlighted in this study: GO personnel do not consider the emotionality of the person they are working with and only dedicate themselves to carrying out their technical work.

What emotions regarding the body and sexuality emerge from the focal experiences with gynecological-obstetric care? In this dimension, the emotions emerging from GOV experiences were analyzed, i.e., via the ways in which reality is felt and experienced, to understand how emotions are constructed within the sociohistorical context that gives meaning via interpretation and understanding to said experience.

The scheme summarizes the strategies that B and NB women use to face gynaecological and obstetric violence. Own Elaboration.

After the consultation, I go to a room to put on clothes, and there, the gynecologist began to touch my butt. My whole body froze; I sweated cold all that precise moment. I saw the closed door, and I said, “I already went.” He would not stop talking about the family at any time and, suddenly, he pats me again. (A., 22 years old, gender, Antofagasta).

They leave me alone in the box. He was crying, he was horribly wrong, with great sorrow. I already practically knew what they were going to tell me [pregnancy loss]. It was the most horrible and hardest experience for me to let go. The insensitivity, the null empathy gave me a lot of anger, everything. (A., 22 years old, gender, undefined sexual orientation, Antofagasta).

From the narratives of medical consultation or childbirth care, fear, anger, anguish and helplessness emerge. This emotional response is conditioned by a social stimulus; for example, in one of the stories, in a situation that threatens the body of the narrator, she has an emotional experience defined by these emotions that alters her approach to gynecological-obstetric care in the future

The doctor arrived and told me that I am not delaying. It makes me feel “terrified” and breaks my bag with something. I had no control of my body, I reduced myself to nothing. I have always felt like a very healthy woman, super active, and I feel that at that moment [labor], I reduced myself to nothing. I had no control of myself, I was scared to death. I felt that what happened that day was my fault. “You did not delay”, which was my body. What happened to my body that was not able to do it? And then, a midwife enters because she saw that everything was complicated, but nobody said anything. (M., 34 years old, female, heterosexual, Antofagasta).

In this experience, guilt and shame are intrapsychic repression devices, in contrast to the discursive power of the health personnel who, in this case, hold the woman responsible for any action, voluntary or involuntary, which occurs during the procedure. In this story, the woman wonders about the nonresponse of her body, dominated by emotions. The natural times of the body are questioned as a mechanism that can alter the course of medical processes, causing inconveniences for the professional team [51,52].

In turn, fear becomes “an emotional signal that physical or psychological damage is approaching, which implies an insecurity regarding one’s ability to bear or maintain [oneself in] a threatening situation” [53]. The confusion and emotional state of the narrator interrogates the medical care and the procedure performed in a place that is supposed to be a safe space for well-being.

I came back three years later; I felt very uncomfortable. She said, “Hey, what is it? You opened your legs and did not close them anymore”. I felt really bad, horrible. She called me to do a cauterization, and all the time with those comments. I wonder why I kept going if I was a miserable person. For me, it was something that I disliked. I was outraged. Then I avoided going, I really avoided going. I went one more time for a vaginal infection, and it was super nasty. I think that was the last time. (D., 34 years old, heterosexual woman, Calama).

Here, there is an offense on the part of the professional attending to genital injuries-comments that denounce the sexuality of the patient and that move away from the doctor-patient ethics and the diagnostic dimension. Thus, the patient questions herself about her bowed or humiliated position in front of the doctor, who, in turn, acts with an offensive hierarchical superiority without dwelling on the emotional impact of her abusive treatment. Among the emotions that emerge from this humiliation experienced in relation to sexuality are disgust, resignation and suffering, provoking an unpleasant experience that strains the continuation of the treatment. As a motivational-affective dimension, in the story, escape actions occur in the face of a painful stimulus, e.g., not returning to medical attention to avoid rediscovering an experiencethat is associated with something aversive or unpleasant [31].

What coping and protection strategies do NB women and people

use to address GOV?

Below, the coping and protection strategies used by people

experiencing GOV are analyzed-these efforts are aimed at

mitigating and facing pain and are executed according to the

evaluation one makes of a threatening situation and the resources

that are available at that time [31,54]. These actions are evaluated

from a gender and intersectional perspective because there are no

better or worse strategies, and, therefore, their success or failure

depends on the contextual factors for GOV [30]. In this sense, a

coping and protection strategy operates not only as an adaptive

response to this type of violence but also according to the entire

neoliberal and patriarchal sociocultural context.

In the collected narratives, the following strategies are emerging agencies, subject to emotional experience: postponement of gynecological consultations and/or change of professional; exposure of the situation; sharing the experience with other women; seeking social and psychological support in networks; evasion of discomfort and alienation from experience; self-training and self-learning for bodily autonomy; questioning the system; and self-defense. We emphasize that none of these fit into the categories of aggression, distraction or emotional relief. This, we believe, is the product of the gender mandate to which female bodies are linked (specifically, to weakness and to the condition of as little discomfort as possible). For this reason, the aforementioned strategies were only analyzed according to those aimed at the problem: avoidance or support-seeking.

I got up from the desk and said, “Doctor, less than a week ago you gave me a scrape (because I lost my baby). You said that I was very exaggerated because I always felt bad. I lost it almost in the fifth month of pregnancy; he was a big baby; he was grown up... I have seen that 5-month-old babies have been able to get ahead”. And he [was] scared because he never expected any reaction from me. I said, “I was with you when I lost my baby less than a week ago, and you come to ask me how the pregnancy is going?! No, I don’t want more with you. I never want to see him again! “ I left and I didn’t care about a doctor, a husband, or anything. I left. (Y, 45 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta).

Being more informed and understanding the process, this (chemical induction) was not necessary; it makes me feel that this wound is closing. (M., 34 years old, heterosexual woman, Antofagasta). According to these narratives, self-training for bodily autonomy with rights allows an attitude of questioning the dominant system, of positioning oneself based on strategies for changing the problematic situation and whose turning point is given by an emotional experience. This action operates as a response to the passive receiving part of GOV, stimulating a change in attitude toward the patriarchal hierarchy to directly face the mandate of obedience that converts users bodies, alienated from autonomy [28].

I didn’t go to the gynecologist anymore because she made me feel uncomfortable. She assumed that I was heterosexual; I did not say anything. (K., 22 years old, bisexual woman, Antofagasta). I had so many bad experiences in gynecology that for me, it was, “Stay on the table and do not listen to the comments. Let them do their job and when they say, ‘get dressed’, get dressed”. As an action plan, disconnect as much as possible from everything that is happening. (A., 22 years old, gender, undefined sexual orientation, Antofagasta).

Among the emerging strategies for avoiding GOV are postponing gynecological consultation, the evasion of discomfort, the alienation from the experience and a change in professional, which are related to the emotional experience of fear and guilt that renders attention aversive and, as a result, triggers the escape behaviors of the patients to avoid this painful situation. Although these can be classified as passive or maladaptive strategies, since the person does not assume the role of managing their pain nor are they aimed at solving the problem, they are survival mechanisms that allow marking distance from the emotional affectation that the GOV may exert in the future [31].

Accordingly, we propose that the way forward is not to change survivors’ strategies from passive to active but to highlight the medical model exercised in GOV, i.e., the avoidance of care can be detrimental to sexual health and reproduction and GOV is a problem in state and public health that generates economic and social costs [1].

We have common feelings, and those same experiences make us want to do things so that this does not happen again. So, that’s very nice. We say that all these things happened to us, but what do we do now so that the girls who are around us do not experience them again? (C., 21-year-old, bisexual woman, Antofagasta).

In the search for support, actions emerge, such as exposing the situation (funa: informal public complaint), spreading the word to other people and seeking social and psychological support in networks. These actions could be considered adaptations for facing GOV since they imply the management of the problem through the guidance and advice that people in a similar situation can provide, decreasing the tendency to avoid strategies [54,55]. In this sense, when shared with other women and dissidents, knowledge is generated with gender awareness concerning how sex-gender oppression affects sexual and reproductive health-a turning point in the establishment of mutual support networks [24].

In the “gynecological and obstetric violence” dimension, the focal consultants have identified both physical and psychological experiences that reflect the medical imposition of protocols- questioned by the WHO- for health care that result in physical, psychological and sexual abuse by medical personnel. These situations have generated the excessive pain and suffering that is typified by international organizations as violence against women that should be punished [8]. Thus, we have also observed other forms of gynecological violence, such as the denial of contraceptive methods, the denial of medical attention to a person of sexual dissidence, the imposition of discourses related to stereotypes of body weight and aesthetics, and the instruction and infantilization of the consultants. These constitute the most relevant conflicts that are part of daily gynecological-obstetric care and are translated into mechanisms for the control of the body and its homogenization. We suggest that the invisibility of these practices is due, among other reasons, to intersectional aspects such as the low sexual and reproductive education of the participants, the hierarchical culture of the doctor-consultant relationship and the low registration of cases of this recently studied problem. This represents an innovative line of research in Chile, where obstetric violence can take many forms and can sometimes be underestimated as theresult of postpartum depression or posttraumatic stress syndrome.

Regarding the “emotional experience” dimension, GOV modifies the feelings of people regarding their body and their sexuality and their way of relating to gynecological and obstetric care, predominantly with feelings of guilt, shame, fear and humiliation. Regarding the strategies with which this group of consultants address these experiences, those professionals who were responsible for these situations establish a dehumanizing hierarchical treatment in which they position themselves by prioritizing their power in the field of health over the consultants. These practices are likely perpetuated via the privatization of health care, which generates deep gaps between public and private establishments in Chile. Likewise, medicine is a training system that is based on hierarchical power models regarding gender and its impact on health. From the intersectional perspective, we highlight the socioeconomic level of the users and its relationship with the quality of their medical care. That is, the greater the vulnerability of the consultant, the more humiliating his or her treatment tends to be [6]. These situations allow us to better understand the silencing and the difficulties driving coping strategies, specifically, to reflect on the violence exerted in the field of delivery care practices and gynecology, both by health professionals and consultants themselves.

It is therefore appropriate to collect a series of proposals that take into account the following interdisciplines that act in relation to women and dissidents in gynecological or obstetric care: Social and psychological work with women in the stages of pregnancy and childbirth and postpartum.

These activities can be carried out in spaces such as waiting rooms and childbirth preparation courses at health centers, among others. Incorporating investigations and more in-depth studies on GOV in medical training, as well as a demand for respect in the gynecological care of people of sexual dissidence and for childbirth that is chosen voluntarily while exercising personal freedom, would effect important change at the social level, resulting in a future transformation of certain power relations.

We suggest that this article, which constitutes a regional axis of a national investigation (Fondecyt 1210212), opens the path for future studies to classify, as femicides, from a feminist and intersectional perspective, the deaths of women due to the violent gynecological and obstetric practices carried out on women’s bodies for cultural, religious, economic, political or medical reasons. These cases are more common among migrant women and economically precarious women, who have less influence on or possibility of making visible or successfully denouncing the violence perpetrated against them.

The authors acknowledge FONDECYT 1210102.