Author(s): Shelley Grierson

Perspectives and value systems inform our views of antenatal care and childbirth, influencing how they are understood and how care is organised. Professional, academic, institutional and cultural views all influence what we consider maternity care to be, how it should be delivered, and how experiences and outcomes associated with it are measured. The objective of this study was to analyse women's lived experiences of antenatal care within NHS England during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, I sought to understand how the continuity of the care women received influenced women’s experiences, with the aim of identifying areas for improvement with respect to well-being and satisfaction with care. I conducted semi-structured interviews with 6 women who had given birth up to 24 months prior. I analysed transcribed texts using a reflexive thematic approach, undertaken through a social constructionist lens. I developed three themes in the analysis. These were: the impacts of poor communication, the impacts of not being heard, and fear of the unknown. Participants emphasised the need for a person-centred care model and more specifically, a midwife-led continuity of care model. Early antenatal care and late antenatal care were identified as two critical periods of care when women require the greatest levels of advocacy and support. Based on this analysis, the NHS maternity framework could make improvements to information organisation and sharing, the encouragement of active patient participation in care, and the promotion of shared decision-making. Greater attention to how holistic perspectives and medical perspectives could be blended to broaden understandings of what successful birth experiences could be, is required to validate women's antenatal needs and subsequently improve maternity care outcomes.

This research explores the perceptions of women's antenatal care experiences within the English National Health System (NHS) during COVID-19. Health models, health systems and professionals influence women's experiences and outcomes. However, personcentred care models that highlight the importance of continuity of care and empowerment in health care decision-making are often rejected in favour of biomedical models. This research aims to contribute to a more holistic understanding of what antenatal health could look like, to better suit women’s needs.

Pregnancy, childbirth and parenthood can be significant events in women’s lives that can produce both negative and positive outcomes [1]. In positive maternity experiences, women can benefit from improved physical, psychological and emotional outcomes, including a stronger ‘sense of self [1-3]. Positive birth experiences can improve reported feelings of elation, satisfaction and empowerment [4]. Negative birth experiences, however, are associated with poorer physical, psychological and emotional outcomes, including feelings of disappointment, the onset of depression or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and delays in future pregnancies [1-7].

Women’s relationships with their maternity care providers are of vital importance. These experiences are not only “the vehicle for essential lifesaving health services, but women’s experiences with caregivers can empower and comfort or inflict lasting damage and emotional trauma” (27, p. 1). These individual experiences stay with women for a lifetime and are often shared between women - which influences broader social perspectives on healthcare systems [8]. O'Brien et al (9) found that the relationships women build with their midwives in particular influence their levels of trust in hospital policies, in the midwives’ abilities, and in their own abilities to prepare for birth [9]. The relationship between woman and midwife can be powerful in influencing maternity care experiences to be considered as either positive or negative.

Continuity of care includes the continuity of care staff (relational continuity) and the predictability and expectations of care (communication continuity). Relational continuity in maternity care has been shown to be a key factor in positive birth experiences [10]. Relational continuity also makes communication continuity much more likely [11]. When antenatal care staff are consistent for women (i.e. women interact with the same professionals for their maternity care experience), it is more likely that a transparent care plan is in place that both care providers and women are familiar with [11,12]. This sets clear and honest expectations for women as to what to expect from their care experience, increases the predictability of their course of care, and promotes a sense oftrust in their care relationships [11]. In the latest comprehensive maternity care survey conducted by the Care Quality Commission, only 34% of women reported experiencing continuity of care in their antenatal midwife appointments [13]. Only 1% of women surveyed did not want to see the same midwife for their antenatal appointments, likely attributed to a mutual relationship between the care provider and woman being difficult [13].

Missed expectations in the antenatal care stage have been linked to poorer parturition and postnatal outcomes [1]. Mismatches between expectations and experiences occur when a woman's expectations of care are not met. Unsatisfactory maternity experiences as a result of such mismatches are associated with increased likelihoods of women developing psychological disorders, such as PostTraumatic Stress Disorder [1]. Lack of choice and control are major contributing factors to these negative outcomes commonly described by women [14].

Fear of pregnancy and childbirth is a widespread norm in Western society [15]. Women are socialised from a young age to approach the process of childbearing with much preparation, and to employ all the resources they can afford to the process [15]. In fact, fear of childbirth is one of the leading causes of women requesting caesarean births [16]. Media portrayals normalise highly medicalised views on pregnancy and childbirth [16]. The media is also hugely influential in its portrayal of birth as “risky, dramatic and painful” and is heavily responsible for the effects that this portrayal has on society (17, p. 40). By extension, this media climate of fear is a contributor to the poorer outcomes associated with medical interventions such as unnecessary caesarean births.

Power imbalances in maternity care manifest themselves when shared decision-making is not prioritised [9]. Women typically value remaining informed and being given a choice when it comes to their own maternity care [9]. Equally important, however, is the continuity of the relationship that women have with their midwife [9]. When one or both of these elements are lacking, women can lose trust, confidence and a sense of autonomy in their pregnancy experience [9]. The impacts of power dynamics between professionals and women can be minimised or even averted when differing professional opinions and expertise are respected [17]. This can include repositioning women as equal to and central within their own care.

Governmental restrictions imposed highly controlled measures on how care within the NHS (and private care) was delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternity care were not just limited to pregnant women. Restrictions on birth partners prevented the majority from attending antenatal appointments, labour, and in some cases the birth itself, and imposing strict time restrictions on visitations after the birth [18]. Denying women this support network may even have a lasting negative impact on affected women [18]. Another impact of COVID-19 on women's experiences of maternity care was the ultra medicalisation of maternity care during this time. This was further exacerbated by the strains of low care staff levels, long shifts for care workers on shift and severe limitations on many medical supplies and resources [10].

The gendered dominance of men in this highly vulnerable area of women's health is both historic and current. Prevailing care models are based upon popular medical opinion, which is still heavily influenced by men [19]. This continues to be so within Western obstetrics-led maternity care. What women view as trusted sources of information and as being most competent in providing their care is very much influenced by social, cultural, economic, historic, and familial influences [20]. In this way, women have been, and continue to be, dictated to in their maternity care [19]. Those in positions of greatest power are most often of a medical mindset and background and are most likely to be men [21].

The scientific view of birth is based on the beliefs of the biomedical view of health and illness. This perspective views pregnancy and birth as illnesses requiring medical intervention [22]. The human body and human health are essentially viewed as mechanical in nature [22]. Successful pregnancy under this model of care is defined as the survival of the mother and baby [22]. As a result of this mechanical and one-dimensional view of health, emotional influences on health are often ignored. This model of care is adopted by the scientific-leaning professionals within the NHS maternity system.

The midwife-led continuity of care model is a person-centred care approach that explicitly advocates for continuity of midwife care. This model is underpinned by a view of pregnancy and childbirth as natural processes, though appreciating there are some circumstances under which medical intervention is necessary. When used alongside adequate risk assessment criteria, the midwife-led continuity of care model is the most effective maternity care model - providing women with the best physical and emotional outcomes for both mother and baby [23].

As a first-time mother to a new baby boy, I have recent lived experience of maternity care within the NHS. I wanted to explore other women's perceptions of antenatal care within the NHS and understand what their expectations and emotional experiences were from these interactions. As a researcher with this recent lived experience on this topic, I am both a member of this group, as well as a commentator

I approached the research and analysis from a social constructionist perspective, and applied a feminist theoretical framework.

Procedurally, Massey University's ethics protocols dictated a comprehensive set of requirements for gaining ethical approval. This involved the justification for conducting my research, as well as for the selection of recruitment channels and participants. It also included the detailing and approval of communications to participants such as informed consent, transcript releases and interview guides. Benefits and risks to participants and researchers, as well as support requirements and cultural sensitivities were also recognised, considered and documented. Special consideration was given to the potential for the triggering of birth trauma. Ethical approval was granted by the Massey University Ethics Committee (protocol NOR22/11) prior to the research commencing

The National Childbirthing Trust (NCT), a charitable organisation for pregnancy, childbirth and antenatal education in the UK wasthe recruitment channel used for selecting participants for this research. Participants all identified as women, were 18+ years of age, and had experienced a low-risk pregnancy within 24 months of participating in the research. Six women were recruited from the NCT. The sample size of the study was guided by the concept of ‘information power’, whereby the more rich and more detailed the data collection, the fewer participants are required [24].

Interviews were conducted using the online conference software Zoom, which also allowed for each interview to be recorded. Using semi-structured interviews, I asked each participant 24 questions relating to their antenatal care experiences (Appendix 3). Participants' identities and privacy were protected by the use of pseudonyms. All the data was collected between June 2022 and July 2022. Each interview took approximately one hour per participant to complete. Individual digital files were also stored securely within privacy-protected and encrypted folders. There were occasions when participants became upset recalling a traumatic event or memory. In these instances, I made the participant aware that I was understanding, supportive, able to stop the recording and the interview, and would be happy to take their lead on whatever they needed. In all cases, participants were happy to proceed after being given a moment to gather themselves, and often explained why they were emotionally triggered.

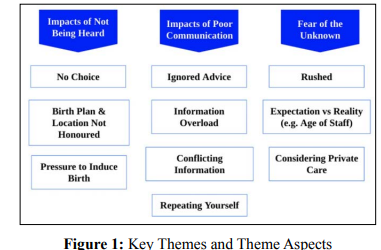

I analysed the data using reflexive thematic analysis. As a framework for conducting the analysis, I was guided by Braun & Clarke [25]. This process began with manually transcribing each interview. Listening back to interview recordings allowed me to ensure that participants' accounts were captured accurately in each transcription. Where necessary, I noted non-verbal responses such as crying, to ensure that the intensity of the response was remembered. Several coding stages followed the transcription of the interviews. Generation of initial codes followed, then the search for themes and the review of these themes. Defining and writing up these themes were the final stages of the coding process. Three key themes developed relating to women's antenatal care experiences. These included the impacts of poor communication; the impacts of not being heard; and fear of the unknown. Together these themes explore women's experiences of how pregnancy care factors can influence perspectives and experiences of pregnancy and birth.

Participants were all first-time mothers and were geographically located in the South and East of England. Women all identified as British and are summarised below in Table 1.

| Participant Pseudonym | Age | Ethnicity | #Children | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Abbie” | 38 | British | 1 | London |

| “Ameila” | 37 | British | 1 | London |

| “Brooke” | 37 | British | 1 | Margate |

| “Denise” | 39 | British | 1 | Hinchingbrooke |

| “Naomi” | 38 | British | 1 | Ashford |

| “Rose” | 39 | British | 1 | Margate |

Of the interviews I shared with the participants and throughout the process of analysis, three key themes stood out as I interpreted the data. These included not being listened to, followed by issues with communication, and fear of the unknown in pregnancy, antenatal care and around the topic of miscarriage. There were also a number of aspects that were part of the overall key themes. I have provided an overview of the key themes and key aspects in a thematic map (Figure 1).

Most of the participants reflected a sense of not being heard during their antenatal care. This was reflected in their lack of choice in the direction their care was taking, their birth choices not being honoured, and feeling pressured into accepting interventions that they were not comfortable with - most notably the induction of labour. Most women shared that information on their birth options, particularly about induction, were not provided early enough in the antenatal journey. In most cases, the conversation around induction only occurred in the lead- up to labour itself, causing participants stress, a sense of urgency in having to make an uninformed and quick decision, and unnecessary added pressure in an already pressurised situation. Participants had not been given the time to familiarise themselves with information about inductions, nor given the space to make informed decisions based on their own preferences. Most participants also shared that information on inductions was not presented to them as a clear choice but as an instruction. This highlighted to me the importance for the ‘cascade of interventions’ to be explained and made clearer, so that women can fully understand their choices and the consequences of these choices. The negative sentiment felt by women around inductions was mentioned by five out of six participants. I also sensed a great deal of emotion in participants' discussions of this topic. It roused responses that were more charged than many other talking points in the interviews. Responses were more passionate and more detailed compared to responses to other aspects of the interview. Some of the participants explained their anger and frustrations, and others their upset and stress. For instance, Abbie shared:

“Towards the end, when I didn't want the induction, that was pretty difficult. I had to like, negotiate with them not to have an induction. And they were not, just not very positive. They have to say what the research says. I did a lot of research on it myself. And it's quite old research that they have, but I know what they're trying to do. They're just trying to keep everyone safe. And so they have to kind of say that, but it was quite difficult too. And it was a little bit upsetting because they were like, you know, you're gonna put your baby in danger if you don't do this induction. And I was like, I don't want it. And I've read other research, which says that that's not the case. So yeah, that was a bit stressful. And I didn't particularly feel heard at that point.” Abbie.

Induction also dictates the location of labour and birth. Five out of six participants had discussed wanting a natural birth in a birth centre, and all five were very distressed when this option was taken away from them. Because inducing labour requires medicating women with synthetic hormones, close monitoring of both mother and baby is required. The birth location then becomes not a choice but a directive - one of giving birth in a hospital labour ward with a high level of medical observation and intervention.

“I sort of felt like when it came to inductions, it was like, right, you know, you've hit this time, and so this is the procedure now, rather than you have a choice” Amelia.

Amelia describes the lack of choice in her situation of feeling pressured into an induction. This demonstrates the negative impact of the unbalanced power dynamic within the care system.

All six participants referenced their frustrations with poor communication. Poor communication was described in several ways, including poor communication of care plans from the outset of early antenatal care (e.g. a lack of visibility for women on what to expect throughout the process), little or no communication within care teams (e.g. deficient handovers between departments or individual members of staff), insufficient communication around upcoming appointments (e.g. inadequate notice given to attend appointments; letters to attend an appointment being lost in the post) and an absence of tailored communication (e.g. feeling they were being treated as a number and not as an individual in tick-box exercises).

Participants discussed the need to regularly repeat themselves to care providers, despite their case notes being made available to these providers. Despite the challenges they identified around communication, participants also all recognised the scale of the job faced by the NHS in delivering maternity care to women across the UK. Participants were all very grateful and thankful for the NHS and understood that resources were limited; their frustrations could thus be interpreted as related to systemic constraints, rather than individual care providers. What care providers could do, though, according to participants, was communicate more clearly about why decisions about their individual care plans were made in the context of resource shortages. They commonly mentioned that they would have understood and been accommodating to shortcomings in care if an appropriate level of communication and explanation were provided to them.

“Communication could have been improved on - within the care team and to me. If you’re new to the case- read the notes. I don’t want to have to explain to four people within four hours - they should know that. It could all be computerised. They’re understaffed. The handoff between departments was shockingly bad. You could do more with the midwife and less at the central hospitals. That would be better. Because she knows you, she knows your story. You’re not in a random room and someone else is telling you something. It’s a disjointed story” Naomi.

Women were often referred back to their maternity notes by care teams, known as the ‘purple folder’, if they had any questions or concerns. But confusion as a result of the poor presentation of key information in this folder was a common complaint among participants. For example, key phone number contacts being located in different areas within the folder making them difficult to find, or confusion over which phone numbers to call for minor queries or major concerns.

“One phone number, for example. That would be, yeah, a better organisation of contacts. It doesn't need to be a one-person contact, but a one-number-catch-all number that you can then link to the early pregnancy unit, the lactation consultants, you know, the labour ward, or your midwife, a gestational diabetes team, you know, all of those things under one roof would be great.” Rose.

Here, Rose expressed her desire for a clearer organisation of care contact information. Multiple participants recalled their difficulties in making contact with their care team as a result of the poor presentation of contact information, or contacting the wrong team as a result, and subsequently missing out on the care that they required.

A common response across all participants was their sense of anxiety and fear of the unknown in their antenatal journey. For all of the women, it was their first healthy, full-term pregnancy. The disparities between care expectations and care realities were exacerbated by immature relationship development between participants and their care teams. This further exacerbated participants' sense of anxiety and fear of the unknown.

Participants commonly described concerns with respect to poor continuity of midwife care. For instance, women felt rushed in their antenatal appointments and had to repeat themselves often; they described being provided with conflicting information and having age and experience concerns with their midwife, all leading to increased anxiety of the unknown. The impacts of poor care relationships, particularly between women and their midwives is known to produce more negative outcomes for mother and baby, compared to positive and consistent ones [26].

“The early antenatal care was very inconsistent in terms of staff. I never saw the same midwife more than once. It was a different person every single time and that's no discredit to them personally because they were all amazing. But I think having continuity even to see the same two or three people. It seemed crazy to me that every time I went back, I had to say clearly they have my notes and the purple folder etc. But I found myself having to say the same thing at every appointment again and again and again and there was no build-up of rapport, no build-up of a relationship because it was always somebody different. That was a big, big negative for me. I think it was an assumption that I had when I first got pregnant that I would be assigned a midwife and she would be with me till, almost till the birth.” Rose.

There was an expectation for many women that they would be provided with greater continuity in their midwifery team, as Rose describes. Several women expressed their surprise in not seeing the same person twice. These experiences exacerbated fears and anxieties of the unknown by adding a layer of inconsistency to participant’s antenatal care. Rose, and most participants, made clear that they felt the midwives had done the best that they could for them, but that they understood that they were stretched within an overburdened system.

One participant, in particular, highlighted to me the additional stress and anxiety added to their fear of miscarriage, as a result of unsympathetic responses by care providers. Several participants with prior experience of pregnancy loss explained how they had had to lower their expectations of antenatal care.

“The experience of having a miscarriage the first time when I was like three months pregnant, and I went to the hospital, that wasreally stressful. And they seemed to act like it was really routine. I was really upset, and they didn't show a lot of sympathy. So I think from that experience, I lessened my expectations. Okay, so you're really super excited when you have your first baby. And you realize that, you know, they're just doing their job. Because of previous miscarriages, I had a scan at six weeks. And that was all good. Yeah. And then I think had a scan at 12 weeks as well. I had like one miscarriage and then what they call chemical pregnancies. And yeah, that reassured me. And then I booked a private scan at 10 weeks just because I was like really nervous. And then that was fine. And then I had the 12-week scan after that. Maybe subconsciously, I didn't really think about it, but I probably was just super excited to have a happy, like healthy pregnancy.” Abbie.

Abbie illustrated how the distress she experienced in her prior miscarriage was exacerbated by the standardised way in which it was treated by her care team (“..they seemed to act like it was really routine. I was really upset, and they didn’t show a lot of sympathy”).

But she goes on to reference the reassurance she felt when she was offered additional scans thereafter, as well as in her decision to opt for a private scan for a second opinion (...“that reassured me”). What is interesting to note here are the impacts of her prior experience on her subsequent expectations of care (“So I think from that experience, I lessened my expectations. I was probably just super excited to have a happy, like healthy pregnancy”). She also valued the reassurance of a second opinion to ease her anxieties about miscarriage, both through the NHS and through private means. Collaboration in her care was important to her and the knowledge that her care was being monitored and coordinated effectively across multiple teams. The importance of trust is central here to how comfortable she felt in her care relationships, and why this sense of trust is so critical to how women experience and perceive their antenatal care.

The research questions, though informed by my own knowledge

of the subject and lived experience in antenatal care, were

unquestionably limited by my specific perspective. I analysed the

data using reflexive thematic analysis and approached the research

from a feminist perspective. If I were to do this research again, I

would recruit more broadly in terms of geography (more diverse

areas of the UK), recruitment channel (alongside the NCT), risk

level (including multiple births and more complex needs) and age

and experience (history of prior birth) of the participants. I would

be interested to understand how these experiences might differ

in different parts of the country, where access to care can differ,

and how women with successful past pregnancies might develop

perceptions and expectations of future antenatal care.

Women from minority backgrounds have poorer outcomes

and experiences in pregnancy and childbirth [27]. None of the

participants in this study identified as being from any minority

group, and therefore limits the applicability of this study. This

disparity in outcomes for women of minority groups suggests that

the urgency for a more person-centred approach to care is perhaps

more urgent than this research alone could highlight. It would

also be of interest to understand how these needs might differ for

women considered as high risk, for example, those experiencing

multiple birth pregnancies (i.e. expecting twins, triplets etc), or

for women with more complex medical histories and needs.

Findings from this research indicate that several areas of the NHS framework could be refined in order to improve women's experiences of antenatal care. Considering participants’ experiences in relationship to the landscape of care, several recommendations could be taken up. These include providing clearer communication to women in their antenatal care, for example providing more notice to women regarding upcoming appointments; making women aware of the benefits of preparing and sharing their birth plan with their care team in early pregnancy; tailoring the information provided to women to make it feel less generic and more personalised; clearer organisation of key contacts for women to make it simpler to find phone numbers for the relevant departments when needed, and better communication within and between care teams to prevent women having to repeat themselves at appointments.

Addressing how care teams ease or add to the fear of the unknown women experience in their antenatal care is another opportunity within the current care framework. Participants described two key periods within the antenatal care journey as critical to their perceptions and satisfaction with care. These were women's interactions with care staff in early pregnancy (the first appointments with their care team) and in late pregnancy (the last appointments in the lead-up to labour and birth). In particular, women's relationships with their midwives influenced their trust in a hospital's capabilities, the staff's abilities, and in their own self-confidence leading up to birth [9]. The key roles highlighted by participants as particularly influential (both positively and negatively) were midwives, sonographers, and in late pregnancy, obstetricians. These interactions between care staff and women offer an opportunity to improve outcomes through the implementation of relatively simple and economical improvements to the current care framework. Professional development training for these key roles on how to improve interactions with women, particularly during these critical periods, could aid in achieving this [28]. Further, women could be encouraged to be more active participants in their own care, rather than passive patients; this may help mitigate the negative impacts of not feeling heard. Care staff could adapt their dialogue with women to be more conversational and less instructional, to demonstrate to women that care decisions are their own choice [29]. Encouraging this open and equal dialogue earlier in the antenatal care journey could help provide more time and space for women to consider their options and make informed decisions [11]. This way of engaging also provides the opportunity to alleviate or even avoid the stress commonly experienced by women in the period prior to the onset of labour, when the pressure to induce birth can impact birth locations and preferences and cause great distress [30].

By educating care professionals to make them more aware of these critical interaction periods for women, and guiding them on how these interactions could be more positively delivered, women could achieve a greater sense of satisfaction in their care stress could be minimised during already stressful periods. These aspects identified as requiring improvement in my research provide an opportunity to introduce a person-centred care model, balanced against the scientific approach to care, and still accounting for economic and organisational viability.

Although not all participants explicitly stated their preference for continuity in midwife care, the knock-on effects of inconsistent care indicated a preference for a more stable midwife-patient relationship. The midwife role was particularly important during this period of time for participants as a result of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, where uncertainty and instability during maternity care were intensified [30]. Birth partners were often not able to attend antenatal appointments or in some caseseven labour [18]. This midwife-patient relationship became even more important in these instances [30]. How women perceive their support system and sense of control within their own care journey is central to how they experience their care [18]. In my research, participants expressed their sense of relief when their birth partner was able to join them for key periods in their care, and also their anxiety when this was not attainable.

Future research in this area could focus on midwives' attitudes toward a more blended approach to the NHS maternity framework. The success of such an amendment to the current framework would only be possible with their support. It would also be of interest to explore how other care professionals within NHS maternity care (such as GP’s, sonographers and obstetricians) perceive the person-centred approach to care and the midwife-led continuity of care model specifically. Finally, it is worth considering how learnings from this period of care during the global pandemic can be applied in other critical care contexts, or in locations of significant staff or resource shortages [31,32].

Hello and greetings. I am conducting a study on continuity of care during antenatal checkups and how it impacts on emotional experiences. This research will help us to better understand the needs around antenatal care beyond just the physical, and to understand emotional experiences related to pregnancy care. I want to speak with women over the age of 18, who have experienced NHS antenatal care in the UK within the past 24 months. Women will also be members of the NCT. Participants must have access to a phone or computer and Wi-Fi in order to join an online meeting to take part in the research.

If you decide to participate, we will schedule a meeting on Zoom (or Skype, Google Meet), depending on your preferences. Before the interview, I will invite you to complete a consent form. Please feel free to ask about any questions relating to the research project / consult with people you trust prior to deciding to participate. Participation is completely voluntary. If you do not wish to participate, you do not have to. You can also choose to: - Stop participating at any time before or during the interview / data collection - Withdraw your data up until one month after your interview

Benefits could include enjoying talking about your experiences. This project may help future NHS antenatal processes and experience improve. You will also receive a €20 gift card to thank you for your time.

Risks to participation are minimal; you are welcome to share as much or as little as you want in response to questions and to not answer questions that make you feel uncomfortable. There is the potential for you to feel upset discussing your experiences if they were challenging for you. Should any distress arise for you, there is also a list of resources at the end of this form.

Interviews will be audio recorded and transcribed. Recordings will be stored on password protected computers. If any identifiable data is shared within the research team, we will use secure (password protected) means to do this. Recordings and transcripts will be securely deleted 5 years after the close of the research. Analysed data may be used in any of the following ways: - Academic publications - Academic and/or community presentations - Policy briefings - Knowledge translation outputs (e.g. blog posts, infographics, webinars, etc.)

You will be invited to choose a pseudonym (fake name) that will be used to identify you in any outputs from the research. If you do not have a preferred pseudonym, we will select one for you.

You are under no obligation to accept this invitation. You have the right to decline to answer any particular question or to withdraw your data or any part thereof at any time until one month after your interview. Participants may ask any questions about the study at any time during participation, ask for the recording to be paused/ turned off at any time during the interview, and be given access to a summary of the project findings when it is concluded.

A full list of mental health crisis teams is available here:

85258 (free text service) https://giveusashout.org/

0300 330 0700 https://www.nct.org.uk/

0300 123 3393 https://www.mind.org.uk/ Family Action 0808 802 6666 07537 404 282 (text support) familyline@family-action.org.uk https://www.family-action.org.uk/

British Red Cross 0808 196 3651 contactus@redcross.org.uk https://www.redcross.org.uk/about-us/contact-us

This project has been reviewed and approved by the Massey University Human Ethics Committee: Northern, Application NOR 22/11. If you have any concerns about the conduct of this research, please contact A/Prof Fiona Te Momo, Chair, Massey University Human Ethics Committee: Northern, telephone 09 414 0800, x 43347, email humanethicsnorth@massey.ac.nz

Perceptions of Continuity in Antenatal Care and Emotional Outcomes During COVID-19

I have read, or have had read to me in my first language, and I understand the Information Sheet attached as Appendix I. I have had the details of the study explained to me, any questions I had have been answered to my satisfaction, and I understand that I may ask further questions at any time. I have been given sufficient time to consider whether to participate in this study and I understand participation is voluntary and that I may withdraw from the study, up until one month after my interview.

I agree/do not agree to the interview being sound recorded. I wish/ do not wish to have my recordings returned to me.

I wish/do not wish to review my transcript.

I wish/do not wish to receive a summary of the research findings.

I agree to participate in this study under the conditions set out in

the Information Sheet. Declaration by Participant:

I hereby consent to take part in this study. [print full name]

Signature: Date:

School of Psychology Albany Campus Auckland

‘Continuity in Antenatal Care: Exploring Perceptions of Care and

Emotional Experiences During COVID-19’

1. What made you want to participate? Pregnancy and birth experiences

I would like to talk to you about your pregnancy and birth

experiences.

2. Can you please tell me a little bit about your pregnancy

experiences?

3. When did you give birth?

4. How was your birth experience?

5. How did you find pregnancy overall?

6. What did you feel went well or not so well?

I would like to talk about your experiences of receiving care.

7. How would you describe your care experiences in general?

8. How many care professionals (including midwives) assessed

you during your pregnancy?

9. What was your relationship like with your midwife(ves)?

a. Did you have the same community midwife for each of your

checkups / appointments?

b. Did you feel heard in your checkups / appointments?

c. Did you feel your needs were consistently addressed by your

midwife(ves)?

10. Did you feel confident in the lead up to labour / birth about

your care providers?

11. Did you give birth in the same clinic as your antenatal

appointments?

a. What was this like for you?

12. Did you have a birth partner?

a. If yes, were they able to be involved in your antenatal

checkups / appointments?

i. What was this like for you?

13. Was there anything that impacted how you engaged with your

antenatal care?

a. Why / Why not?

14. Did you feel supported by your care team throughout your

antenatal care?

15. Do you feel like you received the kind of care you hoped for?

a. Did you experience any gaps in your care experience?

16. How did this experience impact your overall impression of

your antenatal care?

17. How did you feel emotionally when you were experiencing

antenatal care?

18. How do you feel that this impacted on your pregnancy

experience and emotions?

19. What are the first words that come to mind when you describe

your overall antenatal experience?

20. What would you change about the antenatal care framework?

21. Is there anything you would have liked to change about your

antenatal care specifically?

22. Is there anything that could have been adapted in your

antenatal care to have improved your emotional experiences?

Authority for the Release of Transcripts

“Continuity in Antenatal Care: Exploring Perceptions of Care and Emotional Experiences During COVID-19”

I confirm that I have had the opportunity to read and amend the transcript of the interview(s) conducted with me.

I agree that the edited transcript and extracts from this may be used in reports and publications arising from the research. Signature: Date:

Full Name - Printed