Author(s): Ana Julia Pereira Bernardo

Objective: To analyze the relationship between Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Anxiety Disorders (AD) and describe possible damage to the psychic functions in individuals with this disorder. Methods: this was an integrative review of the literature of articles published between 2008 and 2018, selected in the bibliographic databases of PubMed, Scielo and LILACS.

Results and Discussion: In total, 28 articles were selected, of studies conducted with humans and animals. The relationship between levels of BDNF, including polymorphism in the BDNF gene, and AD was observed to have been approached, showing that the neurotrophic hypothesis could contribute to the physiopathology of ADs, including volumetric changes in regions of the brain, comprising psychic functions in patients with AD. Furthermore, studies have shown that the BDNF levels may reflect the effect of antidepressant or neuromodulation therapy, and that exposure to stressful factors may be related to individuals with this genetic variant being more vulnerable to developing AD.

Conclusions: The data obtained in this research pointed towards an inverse relationship between BDNF levels and AD, and to the contribution of the neurotrophic hypothesis to the neurobiology of these disturbances, including damage to the psychic functions. Whereas considering that other studies to not show this relationship, further studies need to be conducted to validate a possible association. It was possible to hypothesize that BDNF, although unspecific, could be a biomarker associated with AD, and could be capable of helping with preventive actions to maintain mental health.

Anxiety disorders (AD) have specific criteria, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V), and are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders [1, 2]. Their symptoms are: sweating, tremors, cold shivers, tachycardia, poor mental state, hyperventilation, in addition to difficulty with concentration, emotional instability, compromised sleep quality and difficulties with performing daily tasks [3]. They are classified into: panic attack, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia, specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder [4].

An American census conducted between 2019 and 2020, before and during the Covid19 pandemic, demonstrated that the rate of prevalence of anxiety increased three time more in this population, rising from 8.2% to 29.4%, with a discrete reduction between April and May 2020 [5]. Relative to gender, in women the prevalence was approximately double the rate in comparison with men [2, 4]. Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) released its major global review of mental health around the world in 2022, showing that in 2019, an estimated 970 million people were living with some type of mental disorder, anxiety disorders (31.0%) and depressive disorders (28.9%) were the most prevalent for both genders [6].

ADs are brain disturbances in which various heterogeneous pathogenic mechanisms are expressed [7]. Their neurobiology is complex, resulting from the interaction of various psychological, environmental and biological factors. They are characterized by a variety of factors related to neuroendocrinology, neurotransmitter circuits and neuroanatomic changes, aggravated by the high degree of interconnectivity between the circuits of the limbic system, brainstem and cortical areas of the brain, which may be of environmental or genetic origin [8].

The physiopathology of anxiety disorders, on which studies have been limited to laboratory studies and experiments with animals in the last few decades, is similar to that of the psychiatric disorder most studied in the area of psychoimmunology, the major depressive disorder, of which the biological mechanisms most recently studied are: neuroinflammation and the immune kynurenine pathway [7].

Exposure to stress, one of the main risk factors for psychiatric diseases, may cause neuroinflammation and have repercussions on neurogenesis, leading to damage in brain plasticity, compromising psychic functions such as learning and memory, and inducing anxious behaviors [9, 10].

Studies have hypothesized that through the presence of inflammatory cytokines, neuroinflammation contributes to deviation of the route of production of the neurotransmitter serotonin. This begins from its main precursor amino acid, tryptophan, by the presence of the enzyme dioxygenase, leading to the production of kynurenine, a compound that can be converted into the neurotoxic metabolite: quinolinic acid [2,3]. This quinolinic acid activates the receptors of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, stimulates its release and blocks its re-uptake by the astrocytes, contributing to it not becoming excessive within and outside of the synapse, increasing the glutamate excitotoxicity, diminishing the production of the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [9].

BDNF is an abundant neurotrophin in the brain, and among its other functions, it is responsible for cerebral plasticity and neurogenesis - the process whereby the neurons are generated from progenitors for integration into the neuronal network-[11].

Further to the neurobiology of ADs, the increase in activity in regions of the brain that process emotion, in patients who have anxiety disorder, this may result from glutamate excess [8]. On diminishing the levels of BDNF, this excess may in turn affect the integrity of the neuronal system, by compromising brain neurogenesis [10].

According to the WHO, approximately half of the cases of AD are diagnosed, 1/3 receive medication treatment, 1/5 (20.6%) seek the help of health services, so that 23.2% receive no treatment whatsoever. Of the others, 30.8% receive medication treatment only, 19.6% receive psychological treatment only, and 26.5 were treated with medication and psychotherapy [4]. At least 1/3 of the patients with anxiety disorders do not respond to pharmacological treatment, and as yet there is no explanation for justifying the reason why some patients respond well, and others do not [12].

Regarding treatment, when compared with medication therapy, physical exercise is considered an alternative for anxiety disorders. Not only does it cost less and have fewer adverse side effects, but it may be associated with the rise in BDNF levels [13]. A research with lifestyle intervention (diet, physical exercise, and change in behavior), showed considerable benefits in cases of moderate to severe anxiety [14].

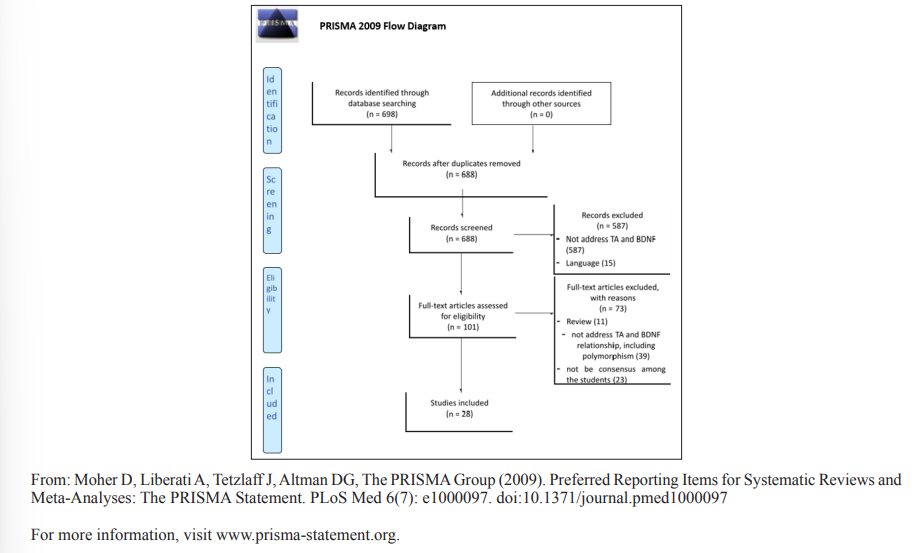

This was an integrative review of the literature, with articles being selected among scientific publications in the Virtual Library on Health (“Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS)”) and Pubmed. The inclusion criteria were as follows; 1) publications in the electronic databases of: PubMed, Scielo and LILACS, between 2008 and 2018, using the following descriptors: Anxiety disorders (transtornos da ansiedade) and BDNF. Analysis were performed in two stages, according to the PRISMA Flow Diagram, Fig.

1. In the first stage, the exclusion criteria were: 1) text written in a language other than English and Portuguese, 2) did not approach the subject of anxiety disorders (AD) and BDNF, including polymorphisms related to the BDNF gene. The exclusion criteria applied in the second stage were: 1) articles with an approach to the relationship between BDNF, including polymorphisms related to the BDNF gene, and AD, in accordance with the diagnosis of DSM V, 2) review articles and 3) absence of consensus among all the researchers about the selection of the article.

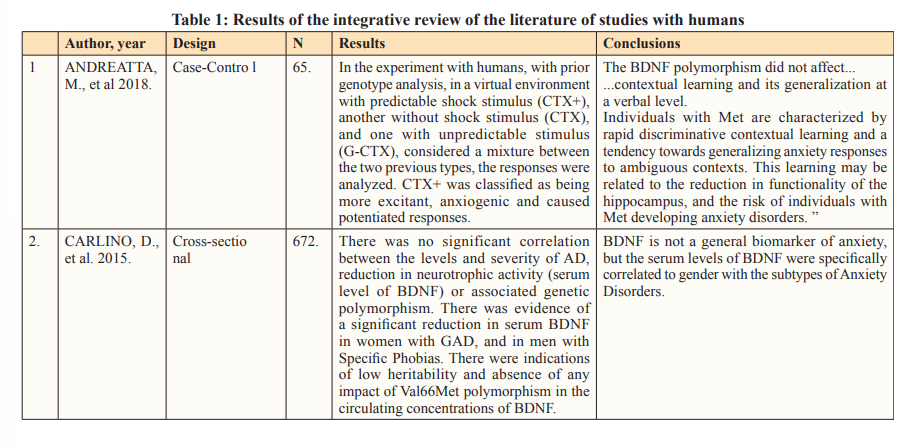

Initially, 698 articles in English were selected, in the period from 2000 to 2018. These went through two stages of analysis, according to the Flow Diagram PRISMA, Fig 01. Initially, 10 duplicated articles were removed. At this stage, the articles were divided among the researchers, who made their selections independently. After applying the exclusion criteria, 101 articles remained for analysis. After this, in the first stage of exclusion, the following were removed: review articles, those that did not approach the relations between levels of BDNF and TA, including polymorphism, and those with absence of consensus about the relations between BDNF and AD among all the researchers, who had analyzed them independently, after having read the complete text. In cases in which there was disagreement, the researchers decided on exclusion of the article. The 28 final articles generated data for filling out Tables 01, 02 and 03. Due to the type of study design chosen, there was no need to approach ethical aspects.

The neurotrophic hypothesis is applicable, particularly to depression, however, the relationship of BDNF with AD has been approached in up to date researches, both in rodents and human beings. In addition to having similar physiopathological characteristics, ADs and depression share a genetic base in various subtypes, therefore, contributing to the emergence of studies about the neurotrophic hypothesis for the physiopathology of AD [15].

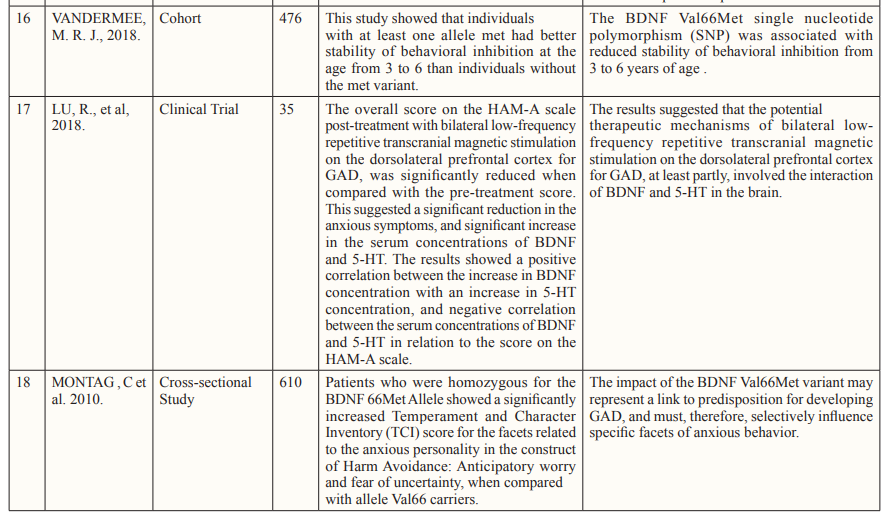

According to CARLINO, BDNF is not a biomarker of anxiety, but its serum levels have been found to be reduced to a greater extent in women with generalized anxiety disorder, than in men, and have been specifically correlated with gender. In a case-control study, conducted with 775 persons, the results did not confirm the hypothesis that the serum concentration of BDNF would be reduced in patients with anxiety disorder, when compared with controls, suggesting that it was improbable that BDNF would be involved in the physiopathology of Ads [16]. The specific finding of gender, showing low levels of BDNF only in women with anxiety disorder may suggest that BDNF was related with the physiopathology of anxiety, only in women, not in men. The findings also suggested that there was no relationship between the levels of BDNF and severity of the anxiety [17].

Changes in the BDNF levels may be related to the reduction in functionality of the hippocampus, pointing towards the risk of developing anxiety disorders, as well greater severity of depressive and anxious symptoms in patients dependent on nicotine, worse conditions of anxiety in individuals with early onset panic disorders, and the occurrence of anxiety in elderly women [18- 21]. One case-control study showed that the BDNF levels were elevated in the lymphocytes of patients with GAD, and so were the levels of BDNF RNAm expression, when compared with those of healthy controls [22].

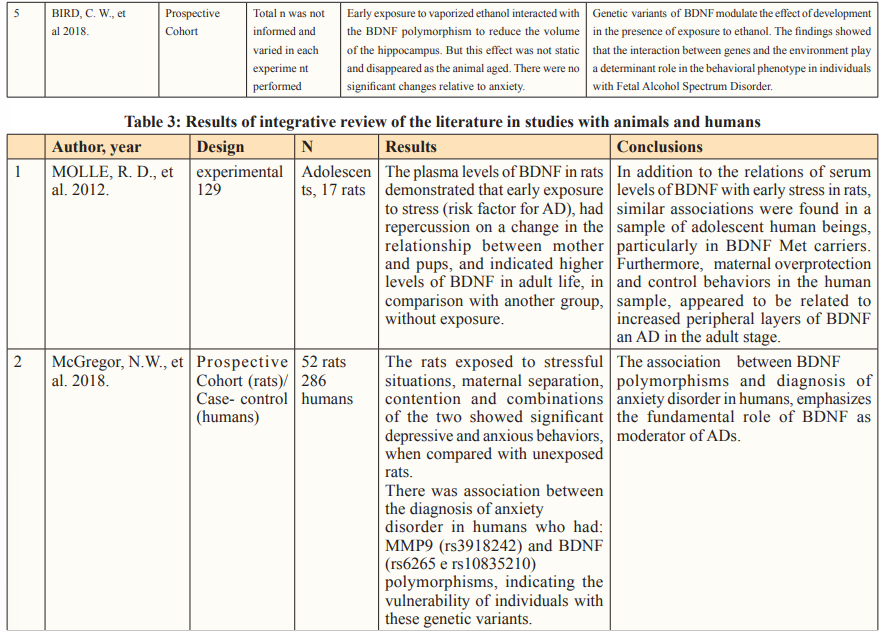

Evaluation of the plasma levels of BDNF, in a research with 129 adolescents and 17 rats, demonstrated that exposure to early stress was a risk factor for AD, and had repercussions on higher levels of BDNF in adult life, in comparison with the other group, without exposure to stress. Moreover, maternal overprotection and control behaviors in the human sample, appeared to be related to increased peripheral levels of BDNF and AD in the adult stage [23].

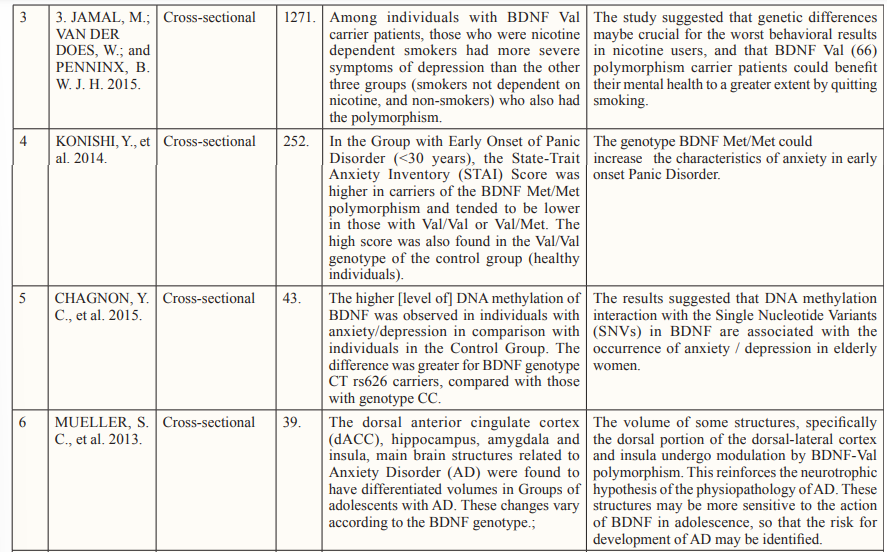

In addition to the serum levels of BDNF, studies have evaluated the correlation between levels of BDNF polymorphism and AD. One study with this objective comparing cases of GAD with healthy controls, showed that there was no significant difference in frequency of BDNF polymorphisms in cases with GAD, in spite of the plasma levels of BDNF being significantly reduced in these cases [24]. According to MONTAG et al. The BDNF polymorphism may suggest a predisposition to developing GAD, in addition to selectively influencing specific facets of anxious behavior [25]. Individuals with anxiety comorbidity had a higher proportion of BDNF polymorphisms, and higher level of neuroticism for avoiding damage than all the other groups [26].

A cross-sectional study showed that BDNF polymorphism was also associated with greater trait anxiety and reduction in stability of behavioral inhibition from 3 to 6 years of age, seen in another study [27,28]. In an experimental prospective cohort study with rats, association was demonstrated between early exposure to vaporized ethanol, BDNF polymorphism and reduction in volume of some regions of the hippocampus [29].

In an experimental study and another with humans, it was observed that rats exposed to stressful situations: maternal separation, contention and combinations of the two conditions, showed significant depressive and anxious behaviors, when compared with controls. There was association between anxiety disorder and BDNF polymorphisms, which could indicate the psychic vulnerability of individuals with this genetic variant. This discovery, in conjunction with the association between BDNF polymorphisms and anxiety disorder, emphasized the role of BDNF in this pathology [30].

Concerning the neurobiology of AD, the volume of some structures, specifically the dorsal portion of the dorsal-lateral cortex and insula, undergo modulation by the BDNF polymorphism, which is distinctly observed when anxious adolescents are compared with healthy individuals, reinforcing the neurotrophic hypothesis of the physiopathology of AD. The modulation of these regions by BDNF suggests that these structures could have greater sensitivity to the action of BDNF in adolescence, and could present risk for AD [31].

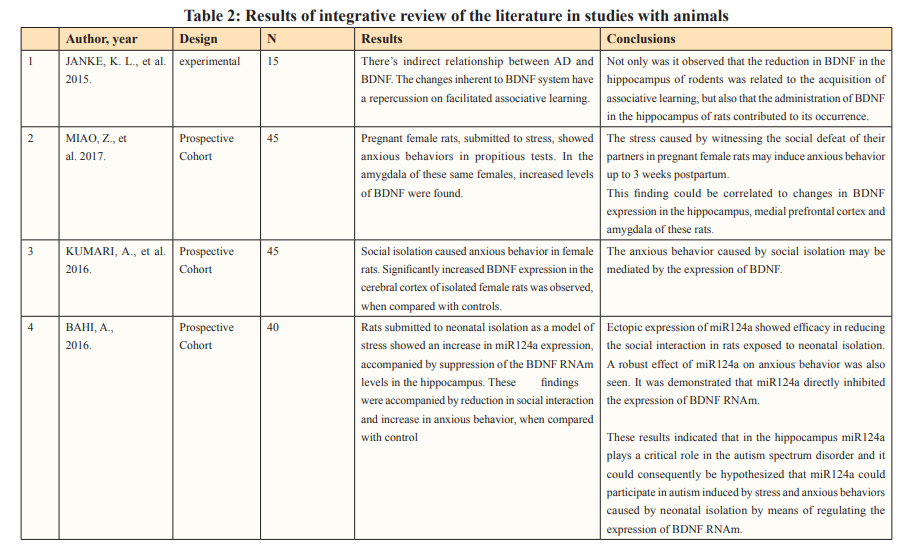

An experimental study with 15 rodents demonstrated association between AD and BDNF levels, with repercussions on facilitated associative learning. In this study, not only was the reduction of BDNF in the hippocampus of rodents observed to be related to the acquisition of associative learning, but also that the administration of BDNF in the hippocampus of rats contributed to its occurrence [32].In a prospective cohort with 45 pregnant female rats, submitted to stress (witnessing the social defeat of their partners), they showed anxious behaviors up to three weeks postpartum. This could be related to changes in BDNF expression in the hippocampus, prefrontal medial cortex and amygdala, with the expression being reduced in the hippocampus, and increased in the amygdala [33].

Furthermore, in a prospective cohort with 45 isolated female rats, significantly increased BDNF expression in the cerebral cortex was shown, when compared with the control, in addition to anxious behavior [34].

From this perspective, studies have pointed out that the Val/ Met genotype represented an independent risk factor for AD in childhood and adolescence, reinforcing the hypothesis that BDNF has neurobiological characteristics that have influence in the genesis of anxiety [35]. Furthermore, LAU et al [15], in a study comparing healthy adolescents with individuals with AD, considered the activation of brain structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus, as findings in BDNF polymorphism carriers, also considering that the activation was modulated by BDNF. Therefore, it was concluded that lower levels of BDNF were associated with the expression of AD symptoms during adolescence, possibly also playing a role in the long term effects on individuals.

A case-control study with 93 participants, showed that BDNF polymorphism carrier patients with prostate cancer, were at greater risk for hypercortisolism secondary to stressful experiences than patients who did not have the allele, data that could be important for preventing GAD in men with prostate cancer [36]. Further to the relationship between stress and BDNF, in an experimental prospective cohort, autism induced by stress and anxious behaviors caused by neonatal isolation could be hypothesized, by means of regulating the expression of BDNF RNAm [37].

According to the studies described above, when considering that both plasma levels of BDNF and BDNF polymorphism could be altered in AD, it would be plausible to question whether both, although unspecific, could be biomarkers of AD. A population based cross-sectional study has suggested that BDNF could be characterized as a biologic marker associated with AD, to the extent to which it may be involved in the neurobiology of GAD, and considering the association of the BDNF polymorphism as risk factor for the occurrence of the disease [38]. A research conducted with pregnant women with GAD, showed reduced serum levels of BDNF when compared with healthy women, which explained the reduced fetal levels of BDNF in the umbilical cord. The duration of maternal GAD showed a significant effect on the reduction of fetal BDNF levels, however, without association with the severity of the anxious symptoms [39].

In spite of the increase in BDNF representing a reflection of normalization of the physiopathology of the disease, the mechanisms of BDNF, isolated, could not be pointed out as being responsible for the response to antidepressants. However, considering that a study with Duloxetine increased the plasma levels of BDNF in patients with GAD, this suggests that the increase in the levels of BDNF reflected the effect of the medication therapy [40].

Regarding neuromodulation treatment for GAD, with rTMS (bilateral low-frequency transcranial repetitive magnetic stimulation) on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, at least partially involves the interaction of BDNF and 5-HT in the brain [41].

FUNADESP (Fundaçao Nacional para o Desenvolvimento do Ensino particular) - National Foundation for the Development of Private Schooling

The studies were observed to point towards the relationship between levels of BDNF and AD, with change in the levels of this neurotrophin in both humans and animals. However, further studies are necessary to present evidence of this association which, if proved, could contribute to action of prevention of AD in the services of mental health care, from primary prevention, including improvements in lifestyle, through to secondary prevention, with early diagnosis, considering the possibility of validating the use of BDNF as a possible, although unspecific, biomarker for mental health.