Author(s): Melissa Matheus MD, Alejandro Serrat DO, Ivanka Vante MD and Anita Shinde MD

Cerebral toxoplasmosis is the most common opportunistic central nervous system (CNS) infection, affecting patients with advanced/untreated acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Cerebral toxoplasmosis is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii typically and it usually occurs in immune-compromised patients with a CD4 count below 100cell/microL [1,2]. Left untreated, symptomatic patients can progress to coma within days to weeks, significantly increasing rates of this population’s morbidity and mortality. Cerebral toxoplasmosis is rarely encountered before the diagnosis of HIV infection is established, which is why seemingly benign neurological complaints can be easily overlooked.

The most common central nervous system opportunistic infection in patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is toxoplasmosis. Approximately 1.2 million people in the United States (US) are infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) 14%, (approximately 1 out of 7 persons) are unaware of their infection according to CDC data from 2018. Of those with AIDS, central nervous system toxoplasmosis occurs in 3-15% of patients in the United States, and up to 50-75% of patients in some countries of Europe and Africa. This intracellular protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, is typically acquired through ingestion of infectious oocysts, from soil or cat litter contaminated with feline feces, or undercooked meat from an infected animal. Once T. gondii oocyst is ingested, the organism invades the intestinal epithelium and disseminates throughout the body. In immunecompetent individuals it will lie dormant within tissues for the lifetime of the host as a latent infection. In immunosuppressed patients with Toxoplasma Gondii, especially with AIDS, the parasite reactivates and causes disease in approximately 30% of cases when the CD4 count falls below 100 cells/microL [1,2].

Clinical presentation of cerebral toxoplasmosis also known as toxoplasma encephalitis (TE) occurs with reactivation of a dormant toxoplasmosis infection and most frequently presents with signs and symptoms of central nervous system disease. Patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis typically present with headache and/or other neurologic symptoms. Fever is usually, but not reliably, present. Focal neurologic deficits or seizures are also common. Mental status changes range from dull affect to stupor and coma as a result of global encephalitis and/or increased intracranial pressure. Less common, Parkinsonism, focal dystonia, rubral tremor, hemichorea-hemiballismus, pan-hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, or the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion may dominate the clinical picture. In some patients neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as paranoid psychosis, dementia, anxiety, and agitation, may be the major manifestations. Although less common, extra-cerebral disease can also occur, pneumonitis and chorioretinitis being the most common extracerebral manifestations. In rare occasions it may present as a systemically disseminated disease, which has a 100% mortality rate if left untreated [7]. Thus a high index of suspicion is essential, particularly when less common and isolated nonspecific manifestations are observed. Cerebral toxoplasmosis is known to be preceded by many other AIDS defining illnesses and is rarely seen as the initial presentation in a newly diagnosed HIV patient [8]. Here we discuss a 27-year-old patient who presented with symptoms of cerebral toxoplasmosis even before diagnosis of HIV was established, his only chief complaints being diplopia, dizziness and slight loss of balance for a period of roughly one month, with a single unusual physical exam finding of anisocoria.

A 27-year-old Cuban male with no significant past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) due to persistent diplopia onset twenty days prior to this admission. Patient describes binocular double vision, painless, worse with left sided gaze and when focusing on near objects and a generalized sensation of dizziness. He also reports slight loss of balance related to his inability to focus his vision. Upon further questioning he does report a recent viral-like illness with associated lymphadenopathy and one episode of diarrhea that has since resolved. He had pressure-like headaches predominantly nocturnal that began twothree weeks prior, which had since subsided. He was seen by his primary physician two weeks prior to emergency department ED visit with reportedly unremarkable laboratory work up and as per patient, a CT of the head and neck showed two enlarged cervical lymph nodes which initially concerned his primary physician of a hematological malignancy. Unfortunately, none of the reports were available for review on evaluation. In the ED, the patient denied any other symptoms besides initial chief complaints when questioned by systems and denied any recent trauma, high-risk social or recreational habits aside from smoking, with cessation five years ago. He acknowledges having only two heterosexual sexual partners.

On physical examination he was found to be alert, awake, oriented to person, place and time. His temperature was 98.7F, heart rate 87 beats per minute, respiratory rate 17/minute, blood pressure 131/ 64 mmHg, SpO2 100% on room air, height 157 cm, weight 70 kg. A focused neurological exam revealed anisocoria with the right pupil measuring approximately 4 mm compared to the left pupil measuring approximately 2mm and no extra ocular muscle abnormalities or nystagmus was noted. Both pupils were reactive to light and accommodation. No focal neurological deficits noted. Extremities revealed no skin rash or track marks. CT of the head performed on admission was concerning for a focal lowattenuation area located throughout the inferior aspect of the right thalamus extending into the right midbrain concerning for recent infarction. Initial laboratory testing was significant for bicitopenia with a hemoglobin of 13.1 (14.0-18.0 g/dl)/ and a white blood cell count of 4.2 (4.70-6.10 x 109/L) significant for an elevated relative monocyte count 11.5 (absolute count: 0.5), elevated ESR (25mm/hr), elevated CRP cardio (6.9mg /L). Magnetic Resonance Angiography of the head without contrast showed no vascular occlusion or intracranial aneurysms. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the head with and without contrast showed a decreased T1 & T2 signal intensity mass lesion with rim enhancement and extensive adjacent vasogenic edema measuring 1.2 cm x 1 cm x 1.3 cm within the right midbrain extending into the basal right cerebral peduncle and a second similar lesion within the left basal ganglia in the superior aspect of the left lentiform nucleus which measures approximately 1 cm x 0.6 cm x 0.8 cm. Viral infection panels including a sexually transmissible screening panel were ordered on admission, which came back all negative aside from a rapid HIV antibody test, which revealed a positive result. The patient had no prior known seropositivity. Given the above findings and high clinical suspicion for cerebral toxoplasmosis, infectious disease was consulted and recommended to defer biopsy given the increased likelihood of the diagnosis of toxoplasma encephalitis in the setting of a reactive HIV 1/2 p24 Ab direct test. Treatment was initiated immediately consisting of a 21day course of pyrimethamine 75mg oral daily, sulfadiazine 1,500mg oral four times daily and leucovorin 25mg oral daily. Adjunctive studies were negative for G6PD deficiency. On day 3 after admission, the patient reported gradual improvement of symptoms with laboratory results for Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin G (Ig G) quantitatively reported elevated at 217 UI/mL (normal low 0.0-7.1UI/mL), thus supporting diagnosis. Of note HSV1 IgG and EBV DNA PCR were also positive but no further treatment was recommended given he was asymptomatic from these viral infections; of note RPR testing was negative. On day 5, results for total CD4 count were 81/uL (359-1519/uL) and the HIV 1 RNA quantitative viral load resulted at 2,000,000 copies/ml confirming the diagnosis of AIDS. Patient was educated appropriately on the diagnosis and results throughout his hospital stay and was set up to follow with ID to begin HAART within 2 weeks of initiating toxoplasmosis treatment, as per current guidelines, upon discharge.

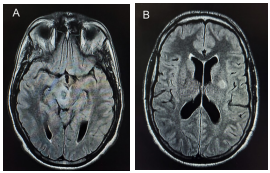

Figure 1: MRI T2 weighted sequence showing 2 rim-enhancing lesions right midbrain (A) and left basal ganglia (B) with adjacent vasogenic edema suggestive of cerebral toxoplasmosis.

A definitive diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis requires identification of a compatible clinical syndrome (ei, headache, neurological symptoms, fever), identification of one or more mass lesions by brain imaging CT or MRI ideally, and detection of the organism in a biopsy specimen the gold standard. However, for most patients presenting with central nervous system (CNS) disease, a presumptive diagnosis is made in order to avoid a brain biopsy, given the associated morbidity and mortality of this invasive procedure. Most commonly, a presumptive diagnosis is made if the CD4 count is <100 cells/microL, along with the following: a compatible clinical syndrome, a positive T. gondii IgG antibody by serologic testing, and CT or MRI (preferably) showing a typical (single or multiple ring-enhancing lesions). If these criteria are present, there is a 90 percent probability that the diagnosis is TE. For patients who can safely undergo lumbar puncture, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should also be performed to evaluate for evidence of T. gondii, as well as other infectious and non-infectious causes of CNS lesions. If toxoplasmosis is identified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from CSF, the diagnosis of TE is even more likely. Given that the patient met all criteria’s for a presumptive diagnosis, a decision was made to initiate therapy. Of note initial CT brain performed in the emergency department showed focal low attenuation area throughout inferior right thalamus, suggestive of a recent infarction. However subsequent MRI demonstrated the characteristic rim enhancing lesions in the right midbrain and cerebral peduncle with a second similar lesion within the left basal ganglia, highly suggestive of cerebral toxoplasmosis. Thus MRI remains the most sensitive in diagnosing cerebral toxoplasmosis compared to CT scan [13].

Serologic studies in patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis are usually positive for anti-toxoplasma IgG antibodies. The absence of antibodies to toxoplasma makes the diagnosis less likely, but does not completely exclude the possibility of TE. Detection may be unreliable in immunodeficient individuals who fail to produce significant titers of specific antibodies, using insensitive assays for diagnosis or early testing in immunocompetent patients who recently acquired the infection. An immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody response is seen in cases of newly acquired toxoplasmosis or Toxoplasma encephalitis in which case a repeat IgG should be performed within a week or a month of symptoms is recommended [7,8].

In clinical practice, toxoplasmosis treatment is initiated once a presumptive diagnosis is made, with close follow up of symptom resolution coupled with regression of initial brain lesions on serial follow up imaging studies. As per 2019 CDC guidelines, primary treatment consists mainly of the combination of pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine plus leucovorin, which prevents pyrimethamine induced hematologic toxicity. Alternative treatment for those who are unable to tolerate sulfadiazine or fail the above treatment is pyrimethamine plus clindamycin plus leucovorin. If pyrimethamine is not available given scarcity in the US since June 2015, substitute for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (in patients without sulfonamide allergy) or atovaquone (in patients with a sulfonamide allergy) should be used instead. Adjunctive corticosteroids therapy, dexamethasone tapered over several days should only be used for patients with mass effect related to focal brain lesions or edema (eg, individuals with radiographic evidence of midline shift). It is of great importance to transition patients to maintenance therapy (aka secondary prophylaxis) after six weeks of treatment with the initial regimen to prevent relapse of infection. This consists of continuing initial regimen, but at lower doses. If seropositive without evidence of active toxoplasma encephalitis and a CD4 of <100μL, it is recommended to initiate prophylactic TMP-SMX. Prophylaxis/secondary prophylaxis may be discontinued with response to ART by an increase in CD4+ counts to >200 cells/µL for >3 months [9]. Of note ruling out G6PD deficiency should be done prior to initiation of treatment given association with severe hemolytic anemia. Once treatment is initiated, rapid improvement in symptoms can be anticipated. Reportedly close to 50 percent of patients exhibit neurologic response within the first three days of treatment, and close to 91 percent show regression of neurologic symptoms by day fourteen. Most patients will show radiologic improvement by the third week of treatment; therefore, neuroradiology studies should be repeated 2 to 4 weeks after initiation of therapy [10].

A high index of suspicion for an immunosuppressed state, such as HIV infection should be considered in patients with rapidly progressive onset of unexplained central nervous system symptoms with or without high risk factors of this acquired disease. In this case, a single physical exam finding of anisocoria and a positive test for HIV found on routine screening, along with MRI imaging and serologic testing positive for IgG Toxoplasmosis supported a presumptive diagnosis and treatment of toxoplasma encephalitis, within days of initiating treatment patient exhibited improvement of symptoms. Therefore, we strongly encourage high degree of suspicion with routine age-appropriate screening tests for HIV as per USPSTF recommendations on all patients aged 15 to 65 as part of our daily practice as physicians [11-13].