Author(s): Richmond Ronald Gomes

Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome (FHCS) isa rare complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) characterized by inflammation of the liver capsule (perihepatitis) following the spread of a pelvic starting point infection leading to the creation of adhesions. The most commonly involved germ is Chlamydia trachomatis. The condition is named after the two physicians, Thomas Fitz-Hugh, Jr and Arthur Hale Curtis who first reported this condition in 1934 and 1930 respectively. The clinical presentation can be misleading and simulate cholecystitis or other cause of pain in the right hypochondrium. In imaging, it results in a contrast enhancement characteristic of the hepatic capsule at portal time.

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (FHCS) is a clinical presentation that associates adnexitis with perihepatitis. The most common cause was a gonococcal infection but currently C. trachomatis is more and more involved [1]. The inflammation of the hepatic capsule results from ascending infection from the pelvic cavity causing right abdominal pain accentuated while in spiration. Differential diagnosis includes cholecystitis, pneumonia, renal colic, perforated ulcer, and pulmonary embolism [1,2]. We report the case of a patient admitted for suspicion of cholecystitis who presented the Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndromesecondarytopelvic inflammatory disease.Theaimofthisarticle is to demonstrate the challenge in the diagnosis and imaging findings that confirm thediagnosis

Mrs. Nurjahan, a 24 year old recently married housewife, not known to have diabetes mellitus, hypertension or bronchial asthma presented to the department of medicine at Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka with the complaints of pain in the right hypochondrium for 7 days, which progressively increased in severity for lastfourdaysin afeverishcontext (feverat38.5°C). The pain was aggravated by movement, coughing and deep inspiration. Systemic review was remarkable for offensive yellowish, intermittent vaginal discharge for two weeks. There was no fever, cough, hemoptysis, dyspareunia nor changes in urine and stool colour. Neither she nor his husband had no known previous history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). She did not practice any contraceptive method. She had a regular 28-30 day menstrual cycle, with a 5 day flow and no dysmenorrhea.She had no known chronic disease or previous history of abdominal trauma or surgery.

On physical examination, she was afebrile, haemodynamically stable with anicteric sclerae. Cardiorespiratory exam was normal. Abdominal exam was remarkable for severe tenderness at the RUQ with a positive Murphysignon superficial palpation, worst on deep inspiration and mild bilateral iliac fossa tenderness on deep palpation. There was neither clinical hepatomegaly nor splenomegaly. Pelvic examination was remarkable for an offensive mucoid yellowish vaginal discharge, with positive cervical motion and mild adnexal tenderness.

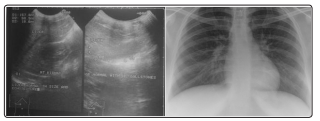

Investigation revealed, the patient had mild anemia (haemoglobin level: 11.8 g/dl), leukocytosis (white blood cells -11,700/MM3), predominantly neutrophils (75.3%)with raised ESR(60 mm in 1st hour) and a positive C reactive protein at 48.89mg/L and a biological assessment of the liver that revealed mildcytolysis (alanine aminotransferase-88 IU/L)without cholestasis (total bilirubin -0.3mg/dL). The diagnosis of cholecystitis had been suspected. An abdominal ultrasound was performed in this setting. It showed a normal size dliver with regular contours. The gallbladder was thin-walled, alithiasic. There was nodilatation of the intra and extrahepatic bile ducts (Figure-1). Chest X-ray posterior anterior view was also normal (Figure-2). High vaginal swab for culture and sensitivity failed to revealed growth of any organism. Endocervical swab was sent for qualitative PCR to detect DNA of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia Trachomatis. Empirical therapy with ofloxacin 400mg bd and doxycycline 100mg bd was started along with NSAIDS. Later PCR to detect DNA of Chlamydia Trachomatis came positive.

Figure:1 and Figure 2: Normal Ultrasonography of Hepatobiliary system and normal chest X ray

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (FHCS), characterized by perihepatic capsulitis and pelvic inflammatory diseases (PID) usually presents with right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain and is frequently associated with symptoms of PID (fever, lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge) [3-6]. The RUQ pain is typically sharp, pleuritic, exacerbated by movement, and often referred to the right shoulder or to the inside of the right arm. It may be associated with nausea, vomiting, hiccupping, chills, fever, night sweats, headache, and malaise [6]. This pain is due to adhesion of the anterior hepatic surface to the abdominal wall [6]. RUQ pain is a common presentation of hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal and urogenital diseases like: hepatitis, liver abscess, sub-phrenic abscess, cholecystitis, appendicitis and pyelonephritis [7].

Chlamydia trachomatis is among the most common causes of PID worldwide and in Cameroon [3,8]. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea have been identified as the main aetiologies of PID and FHCS worldwide although 30-40% of cases are polymicrobial. Bacteroides, Gardnerella, E. coli and Streptococcus have also been found to cause Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome on occasion.These bacterial pathogens cause a thinning of cervical mucus and allow bacteria from the vagina into the uterus and fallopian tubes, causing infection and inflammation [9,10]. Inflammation of the hepatic capsule results from the spread of infection from the pelvis through the right parieto-colic gutter or lymphatic system. FHCS is common among women of child bearing age, with a prevalence of 12-14% in women with PID [7].

The main mechanism of this pathology is attributed to hematolymphatic and peritoneal spread of pelvic infections to the liver and hyper-immune response to Chlamydia trachomatis infection, with both processes leading to peri-hepatic and liver capsular inflammation [11]. This syndrome often presents concomitantly with RUQ and lower abdominal pain. There are also reports of presentations with isolated RUQ pain like in our patient [12]. The presence of isolated RUQ pain poses a diagnostic challenge to many physicians; as RUQ pain is a manifestation of several other hepato-biliary, gastrointestinal and urogenital diseases [3]. However, screening for other genito-urinary symptoms like vaginal discharge through an astute history and a thorough physical examination can prompt suspicion of this syndrome, especially in women of child bearing age as evident in our case.

Diagnosis of FHCS poses diagnostic problems because of its similar presentation with many of the aforementioned pathologies, especially in resource-limited settings where advanced investigations are not available for definitive diagnosis. However, in a well-equipped setting, the diagnosis can be adequately established by excluding other causes and isolating a characteristic pathogen [13]. This involves the use of noninvasive and invasive measures including laparoscopy and laparotomy

Perihepatitis can be definitively distinguished from other causes of right upper quadrant pain only by directly visualizing the liver by laparoscopy or laparotomy [14]. Despite the recent advances in imaging techniques like Computer tomography (CT) scans involved in diagnosing FHCS, with a high sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 95%, we face difficulties in poor countries with limited access to this advanced technology [15]. Ultrasound findings are usually non-specific: perihepatic and pericholecystic effusions and adhesions between the liver and anterior abdominal wall; and are sometimes normal in several patients [7,16,17,18]. Ultrasonography therefore plays a vital role in excluding other diagnosis rather than confirmation of FHCS [14].

Laboratory changes associated with FHCS include a raised CRP, normal or mild increase in WBC, ESR and liver enzymes [19]. For isolation of the aetiology, gene application PCR (polymerase chain reaction) is the gold standard for diagnosing Chlamydia trachomatis [20,21]. In rural areas, the absence of a PCR method for diagnosing chlamydia infections will makes the diagnosis of chlamydial infections longer to pose. Other laboratory diagnostics procedures include chlamydia culture and serology. However, Chlamydia culture is cumbersome, expensive and needs a lot of expertise affecting the assiduity of the results and it therefore is cost-ineffective especially in resource-limited settings where individuals struggle to finance health through out of pocket payments [21]. Chlamydia trachomatis (Enzyme Immuno Assay) with a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity range of 45-70% is widely used in the diagnoses of Chlamydia in resource-limited settings, due to its relative cost-effectiveness [20,22,23]. This method has its limitations as its high specificity makes it a good screening test but the low sensitivity hinders its relative diagnostic value.Laparoscopy is also rarely required, but may be performed when the diagnosis is uncertain and may reveal “guitar string” adhesions of parietal peritoneum to liver.

The management of FHCS includes the use of antibiotics like doxycycline and azithromycin for Chlamydia-associated FHC [24]. This management is relatively cheap and safe, compared to interventional procedures used in advanced cases of FHCS where antibiotic therapy is ineffective. Mechanical lyses of adhesions can be performed surgically if conservative treatment fails [14]. This therefore calls for a need for early diagnosis and treatment of FHCS in resource-limited settings where interventional procedures are not readily available. Emphasis should also be placed on treatment of all sexual contacts to control the spread of STDs.

Physicians in resource-limited settings despite limitations in advanced imaging and laboratory techniques should have a high index of suspicion of FHCS in reproductive females with right upper quadrant pain. Basic laboratory investigations also play a critical role in the diagnosis of this pathology as they help avoid complications and unnecessary surgical interventions.